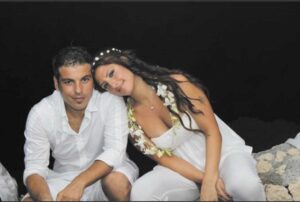

As hearts and flowers help celebrate around the world THEO PANAYIDES speaks to an unusual couple in Cyprus who say if there is love there is a way around the difficulties and tease they are leading the island by example, being unified

It’s a few days before Valentine’s Day – the day of couples and romantic togetherness – and I’m sitting with Michalis Michael and Sukran Ozerdem in the grounds of the State Fair in Nicosia. They’re here for work (Michalis has a medical-services and assisted-living company that’s responsible for administering Covid tests), but it also happens to be where he first met her parents, in 2004 or thereabouts, at a stall for the UN programme where he and Sukran were both working. At the time, they were just friendly colleagues – but they started dating in 2008, got married in 2013 and now have two boys, seven and four. They’re also, of course, bicommunal, a Greek and a Turkish Cypriot respectively, born and raised on opposite sides of the Green Line.

That political aspect is inescapable, and hasn’t escaped media attention – mostly in 2015, when they became the first bicommunal couple to win a Stelios Foundation award in the newly-instituted ‘Partners in Life’ category (it was actually Sukran who gave Sir Stelios the idea; more on this later). They’ve been interviewed by Fox News and featured in The Guardian, not to mention a thoughtful piece by Alexia Evripidou in the Cyprus Mail six years ago. But today it’s nearly Valentine’s Day, and they’re just a couple like any other couple – though also unlike any other, every marriage (and indeed relationship) being powered by its own unique dynamic.

What exactly is their dynamic? Hard to say, but a few things stand out. For a start, they have much in common. They were born a few months apart (Michalis recently celebrated his 41st birthday, Sukran is about to have hers) to middle-class families in Nicosia, and indeed in the same neighbourhood – only bisected by the Green Line, so they knew nothing of each other. Both have the same tattoo, their kids’ names etched across their wrists. Both came from what may be called the organisational sector (his degree was in computer MIS, management information systems; she studied integrated marketing communications) before ending up at the UN. Both also appear to be extroverted, chatty people. Whether because they’re media-savvy or just that kind of couple, they banter frequently:

“It was intense at the beginning, very intense,” recalls Michalis of their relationship.

“‘At the beginning’?” laughs Sukran, mock-offended.

She seems more direct, more candid; he’s a bit more evasive (or diplomatic), the kind who’ll tell a pointed joke or story to illustrate his feelings rather than describe them per se (men are bad at describing their feelings anyway). He’s a live-wire, with a big wolfish smile and a booming voice; she’s a bit more rueful, less exuberant. He’s always been a doer (no surprise that he runs his own company) with a flair for improvisation, not especially romantic but he’ll surprise you with “small touches”. He’s also ingenious in the kitchen, says his wife, able to sling together meals out of scraps and whatever’s in the cupboard – “But the last time you cooked, was when? 1980? Something like this,” she sighs, sparring again.

How would they describe each other’s personality?

Sukran thinks about it. “He’s very, very intelligent,” she begins, and Michalis looks abashed. “I’m almost always thinking simply – but he is so complex… And this sometimes creates a problem with me, because I’m so target-oriented and – to the point. But no, he has to think, he has to sleep on it, etc. But he’s very easy-going, very loveable, very kind.”

“Awww…”

She frowns, not entirely complimentary: “You are – I don’t know the word in English, gicik. You are very gicik.” (Google Translate says ‘a stinker’, which sounds about right.) “He’s [always] doing something on purpose to make me angry. I mean, on purpose! And continuing.” Couples are like siblings, all too aware of what buttons to push and how to get under each other’s skin. “But generally, he’s adorable. He’s nice.”

And Sukran’s personality?

“That’s hard,” he demurs.

“If you don’t feel it, don’t say,” she interjects.

“Well…”

“Yes? We’re waiting.”

“If I have to say one thing, it’s that you can make friends with everyone,” he offers. “She’s really cool, very positive in a group. And she’s very supportive, extremely supportive – in every effort. Even if she doesn’t believe in it!” he adds – and they both laugh uproariously, presumably at some private in-joke. Michalis shakes his head as the laughter subsides: “Yeah… I love you.”

Love is the secret ingredient, of course, the lifeblood of Valentine’s Day, the unseen tide that ebbs and flows – and sometimes goes out altogether – in every relationship. ‘Love means never having to say you’re sorry’ went the line in the movie Love Story – but of course that’s completely unrealistic, all couples hurt each other and try to make amends later. “We spend a couple of days not talking to each other,” admits Sukran, speaking of their often explosive arguments, wryly adding: “Lately no, because he’s so busy.” He’ll come home so tired he often conks out on the sofa, ignoring her pleas to come to bed (she hates that), and meanwhile the kids have been driving her crazy; it’s enough to make you want to be single again. Then again, at one point in our interview Michalis reaches over casually, having spotted a smudge (of dirt, or maybe ink) on her right temple, and rubs it off without saying anything – and maybe that’s the crux, in the end. Love means having someone to rub a smudge of ink off your temple.

Their situation is especially delicate, given what it took to come this far. It’s not something they talk about consciously – but it must weigh on them occasionally, the sacred burden of being bicommunal. Things were indeed intense ‘at the beginning’, like Michalis said – though for years they were just suitably neutral UN colleagues with “good chemistry”, not least because neither was single (he was engaged, she was married). Those relationships fell by the wayside – then one night, inevitably, it happened: they went out with friends, he forgot his cigarettes in her handbag and came to her house to retrieve them (ironically, his smoking is high on the list of things that annoy her now), and nature took its course. “And then our barriers started with the families,” recalls Sukran. “After we started dating. That’s when the real barriers came,” adds Michalis.

The families weren’t exactly bicommunal, “but they weren’t nationalist or anything, they were okay,” she says. (His family may have been a bigger challenge: Michalis describes himself as “holding right-wing ideologies” as a younger man in that Cyprus Mail article.) “Concerned questions were asked by both sets of parents,” reports our piece from six years ago: “What would society say? What about the religious differences? How would society accept a mixed child? They were told to stop their affair but, after two years together, the couple chose to stand their ground.” Those parental concerns weren’t exactly wrong, admits Sukran now: “I mean we faced these – not problems, but we faced these things. But, if there is love, there is a way.”

They dated for years, never quite feeling able to take the next step. “We got married by ourselves, in the end, because they didn’t really accept it,” he recalls – just a civil wedding, followed two months later by a party at Chateau Status in the buffer zone, by which time family and friends had mostly come around. Everyone’s happy now, of course – yet he did lose a couple of friends, says Michalis, people who “blamed my wife for their homes being held by the Turkish army, for example”. Sukran, too, heard some weird comments, like the one (hopefully from a settler, not a Turkish Cypriot) about her husband’s people having come down from Greece after the coup: “They didn’t know that Greek Cypriots used to live here before ’74 as well”.

Sounds incredible – but history books on both sides are notoriously skewed, and besides bicommunal couples were very rare at the time (they’re still rare now). The Stelios Foundation didn’t even give awards to couples six years ago, just business partnerships – but “my wife said: ‘We are a partnership. We have sustainability – you know, children – we deserve an award!’, and she actually submitted an application. We are the first and only couple that submitted to Stelios.” A percentage of the annual awards are now reserved for ‘partners in life’, though it’s a sign of their relative scarcity that Sukran and Michalis were among the winners three years in a row, 2015-17.

So I guess I should ask, I probe gently: What are your hopes for the Cyprus problem?

A long pause. Sukran sighs deeply. “Oh, the Cyprus problem…”

“We are united,” offers her husband brightly. “We’re trying to lead by example.”

There’s a kind of sacred burden, as already mentioned, an implied responsibility. They do indeed lead by example, just by existing; they’ve connected so many people, friends and parents’ friends on both sides of the Line, people (quite often) who’d never reached across the checkpoints before. They’re not just a couple, they’re a symbol – yet it’s hard enough being a couple, whatever Valentine’s Day cards might say. “Relationships are hard,” sighs Michalis. “I mean, you have to do sacrifices,” adds Sukran. “Otherwise, be single.”

Sacrifice what? Your privacy?

“Your ego.”

“You have to give from yourself.”

What’s the other person’s worst habit? Cigarettes in his case, sleeping on the sofa and being a little bit gicik. “What’s my worst habit?” Sukran asks her husband. “Tell me. I am angry person,” she admits to me. “I’m so lovely from the outside but I’m a very angry person,” she insists, ignoring my protestations, “and I don’t have any patience, unfortunately. I know that. I’m trying to change – but kids don’t help!” Michalis, however, is gallant: “She doesn’t have a bad habit, really,” he affirms loyally – though it’s true she’s not very patient. “I mean, she wouldn’t do a [jigsaw] puzzle.” Love means having your anger charmingly rephrased as an inability to do jigsaw puzzles.

There it is again: love, that elusive sprite, the mainstay of Valentine’s Day. “After so many years,” says Sukran, “like 90 per cent of the time, we still say ‘I love you’ to each other when we hang up the telephone.” All the ups and downs surely strengthened their bond – the resistance from nearest and dearest, the knowledge of doing something rare and probably risky, even just the many years it took for the relation to mature from friends to lovers to husband and wife. Romantic couplehood is a funny construct, when you think about it; only nine per cent of mammals are monogamous, according to the internet. Yet we humans do it, ‘for better, for worse’ like they say in the vows – and it brings (or can bring) us to an almost alchemical closeness, not just love but a free-floating bond where love becomes part of the person, flaws and all. A couple is an exercise in accepting the Other, whether that’s a person or another community.

“I believe in a relationship there is a level,” muses Sukran. “After that level, it turns into ‘partners in life’, ‘friends’, ‘parents to each other’. After that, you don’t even think like that anymore – you just say, ‘Finish, I love him! But he is like this. Finish, accept it’.”

And what of Valentine’s Day? They don’t really care about that, say the couple – but Michalis, suitably shamed by our interview, promises Sukran they’ll do something special this time. “Let’s have a special dinner. I’ll cook for you.” It’ll be a nice gesture – though of course they’re long past such gestures, after all these years. Their sense of being a couple doesn’t change because it’s the 14th of February. It’s just there, part of life itself.

“It’s like the joke with the blonde and the headphones, you know?” It appears there was once a blonde who always walked around with headphones on, never took them off, day or night. One day, a friend persuaded her to take them off for a few minutes. The blonde did – and promptly dropped dead. The puzzled friend picked up the headphones to hear what she’d been listening to, and heard a voice saying: “Breathe in… breathe out… breathe in… breathe out…” Michalis laughs, his point made: “So that’s Sukran for me, you know?” I know.