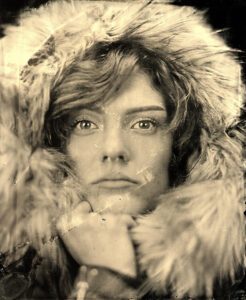

In a man who creates stark and otherworldly ambrotypes, THEO PANAYIDES meets someone who mixes technical and artistic ability and is fascinated by death

Where to begin with Dimitris Mina? Maybe with the fact that he’s one of about 3,000 people in the world making ambrotypes, and one of about 15 making ambrotype cameras? Maybe with the fact that he’s now (since last July) in the Guinness Book of Records for constructing the largest such camera ever? Or maybe just with the fact that he is – by his own, entirely unabashed admission – a moody misfit with a mile-wide morbid streak?

‘Why ambrotypes?’ I ask, expecting the usual bland answer. Well, he explains, he was studying the history of photography – this was about five years ago, when he started getting into the process – “and I liked the fact that this technique, when it was first discovered [in 1851], was employed mostly for post-mortems. So in post-death photography, to remember the dead and so forth – and this really attracted me. Personally, I like death very much.”

Excuse me?

“Not people dying, as such. I just love that it’s the one thing that’s certain, and brings an end to everything… And I’m also fascinated by the denial of death that a lot of people have. Y’know, they turn a blind eye to death, or try to avoid acknowledging that it exists, because they’re so scared of it. I’m not scared at all. Not at all – I couldn’t care less… When my time comes, it comes.”

Some might demur that it’s easy to be unafraid of death when you’re only 35 – but Dimitris comes across as an old soul, a huge bearlike man with a bushy beard and a diligent, unexcitable air. Our setting fits the conversation, a cavernous warehouse in the Aradippou Industrial Area just outside Larnaca that contains his workshop and studio, various equipment belonging to his father – a former musician who now runs a catering business – as well as random stuff that Dimitris, a hoarder by nature, finds abandoned in side-streets and rubbish tips and picks up for use as possible props (or just to have). A punching bag. An entire set of drums, dumped in the trash. A supermarket cart. A red floor lamp which he found and repaired. A giant plastic Nokia phone, abandoned from some event.

Some might demur that it’s easy to be unafraid of death when you’re only 35 – but Dimitris comes across as an old soul, a huge bearlike man with a bushy beard and a diligent, unexcitable air. Our setting fits the conversation, a cavernous warehouse in the Aradippou Industrial Area just outside Larnaca that contains his workshop and studio, various equipment belonging to his father – a former musician who now runs a catering business – as well as random stuff that Dimitris, a hoarder by nature, finds abandoned in side-streets and rubbish tips and picks up for use as possible props (or just to have). A punching bag. An entire set of drums, dumped in the trash. A supermarket cart. A red floor lamp which he found and repaired. A giant plastic Nokia phone, abandoned from some event.

“Okay, Google – darkroom!” he tells his phone (“As you wish, master,” chirps a small female voice) to show me his working conditions – then forgets to turn the lights back on so we sit in the warehouse gloom on a wet afternoon, talking of darkness and death with only some red light and the small square of daylight from the front door (closed when he’s taking photos) to provide illumination. Music plays in the background, a YouTube playlist; he likes hard, frantic stuff, breakcore and death metal. He’s not here all the time, his nine-to-five job being as a content moderator for a web design company (they’re based abroad but he works Cyprus hours, Thursday to Monday, from home) – though he’ll often bring his laptop and spend the whole day at the warehouse, and when he was building the big camera he’d work every evening for three or four months, barely sleeping till the job was done.

The record-breaking camera is there, just behind us, about the size of a phone booth but longer and chunkier. The photo he took with it – of a model in a corset and Victorian dress – measures 200x120cm, more than twice the size of most ambrotypes (60x50cm is the usual maximum, known as ‘mammoth’ by aficionados). “There was quite a big discussion in the community” when he broke the record, he recalls; “Some didn’t take it very well” – notably those who’d been making ambrotypes for the past 20 years, and resented some interloper from Cyprus doing something new. Most are based in the US, where it’s easier to source the chemicals; it took him a year just to find suppliers, says Dimitris, then a few months to gauge the right proportions. “To take a photo now, I need maybe an hour. For someone who’s never done this before, it might take three months.”

He makes his own chemicals, that’s a massive part of it (he makes his own everything). Glass bottles sit on a shelf, like beakers in a mad scientist’s lab. This is collodion, a syrupy combo of alcohol, ethanol, nitrocellulose and various salts (potassium nitrate, potassium iodide, cadmium bromide) which he mixes himself; it’s too expensive to buy, and would come unsalted anyway. Ambrotypes are a type of wet-plate collodion photography, the fiddliest part of the process being perhaps the first step of taking a glass plate and carefully pouring collodion over it so it reaches every corner (I imagine the degree of difficulty being rather like that of a crepe-maker fanning out the batter so it covers every inch of the hot plate). The plate is then submerged in a tray of silver nitrate for about three minutes – rising to 16 for larger or dimly lit photos – after which it becomes photosensitive and can only be exposed to red light. It then goes in the camera (he has seven in total, all made in his workshop), then the rest is relatively straightforward: focus, open the shutter for about 10 seconds, then take the glass plate to the darkroom and apply a special developer and fixer. The former exposes the photo, but as a negative – the subjects appearing as black silver deposits – then the latter turns the silver from black to white, revealing the final image.

Ambrotypes are black-and-white; they’re also remarkable, with a stark, otherworldly quality putting one in mind of the photos of Diane Arbus, or the films of David Lynch and Guy Maddin. A couple gaze out from one of Dimitris’ photos, their blank expressions and faded vintage garments giving them a kind of ghostly elegance; they might be zombies, or someone’s long-dead great-grandparents. Subject-matter is often daring, as in a recent pic of two cross-dressing local lads engaged in some master-and-slave S&M play, nor does Dimitris shirk from the grotesque; his models aren’t conventionally beautiful. “I believe my photos are 60 per cent technical, 40 per cent artistic,” he estimates modestly – and it’s true that technical skill (mixing chemicals, building the equipment) is required, but there’s also an artistic sensibility here. There’s a worldview reflected in these haunted images.

Ambrotypes are black-and-white; they’re also remarkable, with a stark, otherworldly quality putting one in mind of the photos of Diane Arbus, or the films of David Lynch and Guy Maddin. A couple gaze out from one of Dimitris’ photos, their blank expressions and faded vintage garments giving them a kind of ghostly elegance; they might be zombies, or someone’s long-dead great-grandparents. Subject-matter is often daring, as in a recent pic of two cross-dressing local lads engaged in some master-and-slave S&M play, nor does Dimitris shirk from the grotesque; his models aren’t conventionally beautiful. “I believe my photos are 60 per cent technical, 40 per cent artistic,” he estimates modestly – and it’s true that technical skill (mixing chemicals, building the equipment) is required, but there’s also an artistic sensibility here. There’s a worldview reflected in these haunted images.

That same worldview also turns up in his conversation, appearing so easily I almost wonder if he’s playing a persona. Some of his beliefs are wildly original. He doesn’t think there’s life after death, but there may be life before life: “We might be life after death, paying for [what we did], but I don’t think there’s anything after us… Maybe this world is a kind of Heaven or Hell for other, more ideal worlds”. We talk about animals – he lives alone, with two dogs – and he opines that whoever made this world made a mistake in allowing human beings to co-exist with dogs, cats and so on: “Every species should be by itself, then it could live as it deserves. Because we humans are very cruel to the others”.

The recurring thread is a dark take on life, the same air of nameless desolation that hovers over his ambrotypes. Dimitris is a film buff, watching about one a day, and he likes to watch “films that could happen to anyone” – but in fact his taste runs to violent, often gory movies (even very extreme ones, like Martyrs or A Serbian Film), so his definition of ‘things that could happen to anyone’ is obviously bleaker than most people’s. We also talk about the past 18 months – his interest in death must’ve found fertile ground during the pandemic, I suggest – and he nods wryly: “In the past few months I’ve felt like – let me tell you the metaphor I tell everyone – I’ve felt like I walked out of my house, I’m about to get hit by a bus, and I’ve realised it’s going to happen but I don’t know when it’s going to hit me. I’m in that split second between realising and getting hit.”

So he doesn’t think it’s likely to end well?

“That it won’t end well is a given. The only question is how hard it’ll hit.” Going back to the old normal isn’t on the cards, he reckons. “I don’t think we’re going to wake up one day and be like ‘OK, it’s over’. I mean, it’s quite possible that I’ll be an old man and still have to wear a mask – which for me doesn’t mean it ended well.” If he’s still masking up at 70 to go to the supermarket, “then the bus still hit me. Not very hard, but it hit me”.

Is the photography cathartic, then? Channelling darkness into art, that kind of thing?

“It’s an external manifestation of the things I think and feel,” he agrees. “And how I interpret certain feelings. So I have an interpretation [in a photo] of a person struggling with thoughts of suicide. I have an interpretation of schizophrenia, of depression…”

He himself has been through depression, and alienation more generally. He was never the physical type to get bullied at school – “No-one ever dared say anything to me, obviously” – his bearlike bulk also coming in handy years later when he worked as a news photographer for the Athens News Agency, in the chaotic years (2008-12) when that city was shaken by riots. He stood tall among the protesters, braving tear gas and even getting arrested (he spent a night in jail, among other things) – but he was never really one of them, he was just there for work and not overly political anyway, just as he never quite fit in at school. “I was okay with everyone, but – not compatible, let’s say. I was only compatible with one of my classmates, and we’re still friends now.” (This was the friend who helped him hold the record-breaking glass plate – it took two people, at 200x120cm – so collodion could be poured over it.) After all, shrugs Dimitris, his beliefs were much the same as a teenager: “All my life I’ve never been afraid of death. All my life I’ve been reading dark books” – he cites Kafka and Irvin Yalom – “all my life I’ve been listening to dark music”.

He himself has been through depression, and alienation more generally. He was never the physical type to get bullied at school – “No-one ever dared say anything to me, obviously” – his bearlike bulk also coming in handy years later when he worked as a news photographer for the Athens News Agency, in the chaotic years (2008-12) when that city was shaken by riots. He stood tall among the protesters, braving tear gas and even getting arrested (he spent a night in jail, among other things) – but he was never really one of them, he was just there for work and not overly political anyway, just as he never quite fit in at school. “I was okay with everyone, but – not compatible, let’s say. I was only compatible with one of my classmates, and we’re still friends now.” (This was the friend who helped him hold the record-breaking glass plate – it took two people, at 200x120cm – so collodion could be poured over it.) After all, shrugs Dimitris, his beliefs were much the same as a teenager: “All my life I’ve never been afraid of death. All my life I’ve been reading dark books” – he cites Kafka and Irvin Yalom – “all my life I’ve been listening to dark music”.

Is he at least more sociable now?

“No, I’m not sociable! Generally, anything sociable stresses me out. When I’m not in my studio, I’m a bit…” he shakes his head to indicate mental discomfort. “I’m in my space right now, that’s why I’m a little more sociable. But no – I mean, I’ll only go out if I know everyone in the group, and if they all know who I am and what I’m like. Because sometimes I’ll talk all night, sometimes I won’t say a word. My friends know this about me, that I’m just a massive mood swing.”

It’s a silly question really, asking if he’s sociable. It feels right to ask, since we’re having such a nice chat – even in the evening gloom of the warehouse (at one point he relents and calls “Okay, Google, lights on!”; “Yes, master,” chirps the female robot), even when his views seem a little eccentric. Even when he says he’d quite like to be executed by guillotine, even when he recalls how much he enjoyed himself at the Museum of Mediaeval Torture Instruments in Prague, his tone is affable and congenial – yet it’s still clear that he must be something of a loner, just because of the ambrotypes.

Dimitris Mina isn’t just a photographer, he’s a one-man show; one could even call him an obsessive – and indeed he’ll accept that description (he’s been diagnosed with OCD, he notes). “Yeah, it is a bit obsessive that I want to do everything by hand, that I want to control everything myself.” Control is important, mixing his own chemicals, crafting his own bespoke cameras and sometimes disturbing images – he sells a few, and he does get commissions, but they’re not the kind of art most people want to hang on their living-room wall – in the companionable gloom of this lonely warehouse, with his music and obliging Google robot for company. Being in the Guinness Book of Records is great, he says, but it’s not the real point: “At the end of the day, I did all this for me. Just for me”. His photos are extensions of himself, suffused with a bone-deep, inexplicable melancholy.