For years one of Cyprus’ most famous artists lived and worked in one of Famagusta’s most historic buildings

“My uncle used Palazzo as his studio for many years,” says Aris Finiefs, an 85-year-old, retired seaman and descendant of one of the Famagusta’s best-known families.

“He had very good relations with Turkish Cypriots inhabitants of Famagusta’s old town. He only stopped going to the Palazzo when the troubles started in 1963.”

The uncle Finiefs refers to is George Pol Georghiou, one of Cyprus’ most famous artists. The Palazzo is the so-called Queen’s House located just a two minute walk from Famagusta’s mediaeval cathedral of St Nicholas and the remains of the Palazzo del Proveditore.

According to Cypriot lore, this was the place where Caterina Cornaro, the last queen of Cyprus, found shelter after the death of her husband James II and less than one-year-old son James III.

“We don’t really know if it is true but this is what we think,” says the art historian Anna Marangou, whose family also comes from Famagusta.

“It is definitely a palazzo. It has a very beautiful entrance. It is part of Venetian Famagusta. There were a lot of palaces around the Palazzo del Proveditore. And we know that one of them, a small one, belonged to the queen.”

The Palazzo del Proveditore, originally built by Lusignan Kings, was where Caterina lived during her short marriage to James.

According to the book “Historic Cyprus” by Rupert Gunnis, the British historian who lived in Cyprus in the 1930s, very little was known about the palazzo. “Besides the Palace [Palazzo del Proveditore], little remains of domestic architecture except that of a house, a well-preserved example in the style of the Italian Renaissance. Nothing is known of its history,” he wrote.

Finiefs says that while he can’t remember when the building came into his family’s possession, he is certain that it was definitely theirs in 1918 when his grandfather Polyvios Georghiou, one of Famagusta’s wealthiest merchants, died at the age of 51.

“He left behind him three children — two daughters Elengo and Katina, my mother, and my uncle George. I know that in the 1930s the building was rented to the British government and used as a women’s prison.”

In her book “136 Hermes Street and the Painter George Pol. Georghiou”, Aris’ sister Rima Outram writes that in 1946, Georghiou decided to move to the Palazzo after her parents, Leonidas and Katina Finiefs, returned to Cyprus from the United Kingdom.

Outram says that before that the artist painted in one of the large rooms in the family’s huge old mansion located at 136 Hermes Street in Varosha.

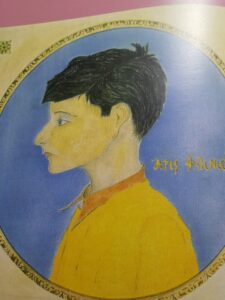

“Leonidas (…) was a doctor and George realised that he would need to offer his studio for use as a doctor’s consulting room. (…) He thought of the Palazzo. It would certainly make a good studio. (…) The site consisted of three enclosing, exterior Venetian walls, with a door and window. The inside was empty apart from a small, roughly made building constructed on the rubble of the fallen interior and accessed by some steps,” she wrote.

“Later the rooms were whitewashed and colourful old plates embedded in the walls.”

There was also a large carved Cypriot frieze, that the artist carefully covered with bright paint himself. He also added a shower room and a kitchenette. The place made him happy.

Rima and Aris did not meet their uncle until they were 11 and nine years old and found him fascinating.

He like to put groups of words together, enjoying them for their rhythm rather than their meaning, often using the same word over and over again. He would greet small children with the word “akatikito”, meaning “uninhibited”.

Rima writes that when Georghiou’s father died, 18-year-old George was sent by his mother Mariolitsa to the United Kingdom to study law. However, rather than concentrating on his studies, the young artist in waiting preferred to sit in the cafes of London and Paris where he would talk to the leading artists of the day, such as Augustus John, Ben Nicholson and Vanessa Bell. In this way he got to know the American art collector Peggy Guggenheim and the polyglot scholar Jean de Menasce. Later, in the 1950s, he was to befriend Lawrence Durrell and Patrick Leigh Fermore.

On returning to Cyprus in 1933 in response to his mother’s entreaties, he reluctantly joined the newly founded Orphanides and Murat shipping agency. As Outram puts it, he sulked for a year before quitting. Not long after, his good friend, the artist John Piper sent him a large packet of watercolour paper from the UK and he managed to acquired an easel in Nicosia. Soon he started painting. Almost around the same time he met Trude, the woman he would marry but not until some 20 years later.

“Trude [Richley] was a very nice person, I liked her a lot,” Aris Finiefs recalls. “She came to Cyprus from Austria. I think her family had a hard time there. Her father was an oficer in the army and her sister was very religious. And Trude? Trude joined a ballet troupe, came here and met George.”

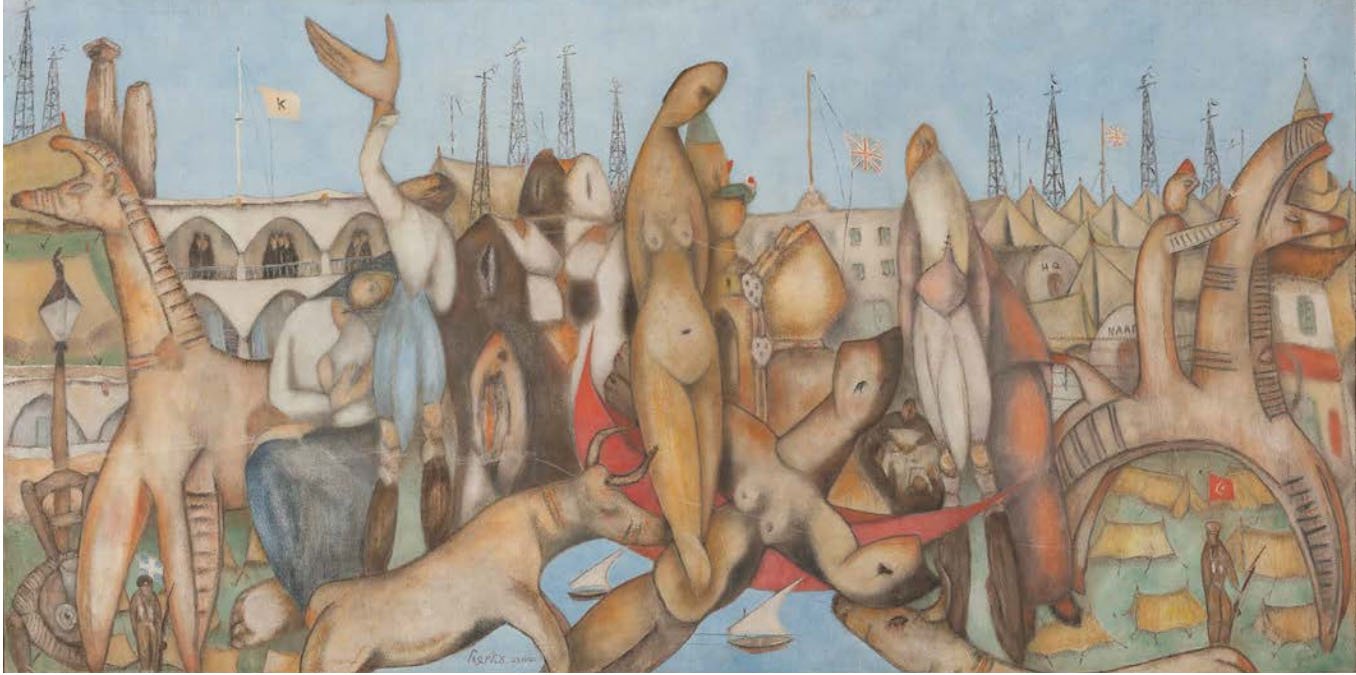

According to Outram, George got his first real breakthrough as a painter in the course of the Second World War when thanks to some British army connections he was allowed to climb Famagusta’s Venetian Walls and permitted to use that privileged overlook to paint the activities going on below him in the port. The British Council helped him acquire the oil paints be used to execute a series of splendid maritime paintings during this time. To this day, one of them hangs now in Winston Churchill’s house, at Chartwell.

“By the 1950s his was a very strong presence and people who understood art were amazed by his works,” Marangou says. “He was cosmopolitan, he knew European heritage, so everybody expected he would be heavly influenced by European art. Instead his images were strongly immersed in Cypriot life, as he came out with this very Cypriot soul.

“He went on to exhibit in the United Kingdom, in France and in Italy, and he would also proudly come back to Cyprus to show his works here. He didn’t shy from difficult subjects, his canvasses reflected the growing tensions on the island.”

While there was no shortage of people wanting to buy his works, often he would refuse to sell if would-be clients failed to pass his “sober and dull” test.

Outram describes one such situation. Somebody wanted to buy one of his large paintings but, having complained about the price, asked for something smaller instead. Georghiou offered him a smaller work but for three times the money of the larger painting. When the buyer queried and challenged this, he was promptly put in his place by the artist who coolly responded: “I do not sell by the yard.”

Starting from the early 1950s, he gradually began moving his studio back to the family mansion in Hermes street. By then Rima’s and Aris’ parents had built their own house and Trude made it clear she didn’t want to live with him full time in the Palazzo. About the same time he befriended the Izzards, a British Cairo-based family interested in spending more than half the year in Famagusta. Given this opportunity, he decided to rent the Queen’s House to them.

Ten years later writer Molly Izzard was to describe their life there in her book “A Private Life”. Coincidentally, her husband, Ralph Izzard, a journalist and naval intelligence officer, was the inspiration for one of the prototypes in Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels.

Back to Molly: “So complete, and so self-contained, did our life in the palazzo appear to me, that it came as a surprise to me the other day to hear someone recall the spartan conditions under which we lived. It is true we had few modern conveniences, and what we did have were erratic and makeshift. The electric current was feeble, and invariably failed during the tremendous thunderstorms. We cooked on a kerosene-stove and on primuses and whenever there was anything big to roast, it was carried around to the baker’s and put in the oven along with the bread.”

The Izzards lived in the Palazzo surrounded by the Turkish Cypriots who were majority in the old town of Famagusta. Georghiou would visit them regularly and when Rima and Aris were back in Cyprus from their schools in the UK they would play with the Izzards’ children.

“George was the only Greek I met who spoke of the Turks with respect and appreciation, and who cherished their town with a humane and sardonic affection,” Molly wrote. “Ah, my dear, he would say when I was a boy, this town was like a dream. I used to come here, and think I’d never see anything like it again. And I never have.”

Georghiou’s feeling that the old world was slowly disappearing soon got a jolt and was unwittingly accelerated when in 1954 the Izzards chose to move from Cairo to Beirut and left the Palazzo.

As the Greek Cypriots started fighting to end colonial rule, friendships with British people were frowned upon, and a dusk-to-dawn curfew was imposed by the authorities.

In 1954, Georghiou finally married Trude and they began to spend time in Nicosia where he was renting a flat. In 1960 he painted his renowned “Rebirth of Cyprus” and he had a large and very successful exhibition in Athens. Then, in 1963, Trude became very ill and, a series of trips to consult doctors in Vienna and London notwithstanding, was to die in London in 1965.

“After Trude died, my uncle went into a deep depression. He didn’t care about anything any more. He was lonely and stopped painting. I never realised how much he loved her. He died in 1972. And most of his paintings disappeared from his house in Hermes Street in 1974. Luckily a large group of them was returned to us by Mr Akinci a couple of years ago,” Aris Finiefs says.

He was referring to the 219 works of art, including some by Georghiou, which had been in the Famagusta municipal art gallery at the time of the invasion and remained in Turkish Cypriot hands until they returned by then Turkish Cypriot leader Mustafa Akinci as part of a confidence building measure in 2020.

And what happened to the Palazzo?

“In the early 1960s he rented it to a Turkish Cypriot family. They were in their late 50s or early 60s and used to come to our house in Varosha every month to pay him rent,” says Finiefs.

“After 1974 we didn’t see the Palazzo again until the crossings opened in 2003. Now I know what happened later: the daughter of the couple was married to [former Turkish Cypriot leader] Dervis Eroglu, and now his daughter has made a restaurant there. But we still own the place. I and my sister Rima, we have the title deeds,” he says.

“Last year I went to see it. It is still there. Not exactly the same but still there. Even some of his wall paintings are still visible.”

Sources: Historic Cyprus by Rupert Gunnis; A Private Life by Molly Izzard and 136 Hermes Street And The Painter George Pol. Georghiou by Rima Outram