Varosha, the once vibrant modern sector of the mediaeval era-walled port city of Famagusta, has been one of the world’s biggest ghost towns since August 1974.

By Michael Theodoulou and Jean Christou

Its 40,000 Greek Cypriot inhabitants fled the advancing Turkish invasion army, taking few possessions in the belief they would be able to return within days.

The Turkish military soon surrounded the empty, and by now looted town with a barbed wire fence that extends into the sea to keep people out. Varosha was for decades entered only by Turkish military patrols and the occasional UN visitor until 2020 when the Turkish side unilaterally decided to open the fenced-off area, causing shock, outrage and heartbreak across the Greek Cypriot community, sparking protests, and drawing wide condemnation from the international community.

While houses in numerous other Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot villages abandoned in 1974 had been resettled by displaced people or used to house incoming Turkish settlers. Varosha had been the anomaly. It was special — a Forbidden City.

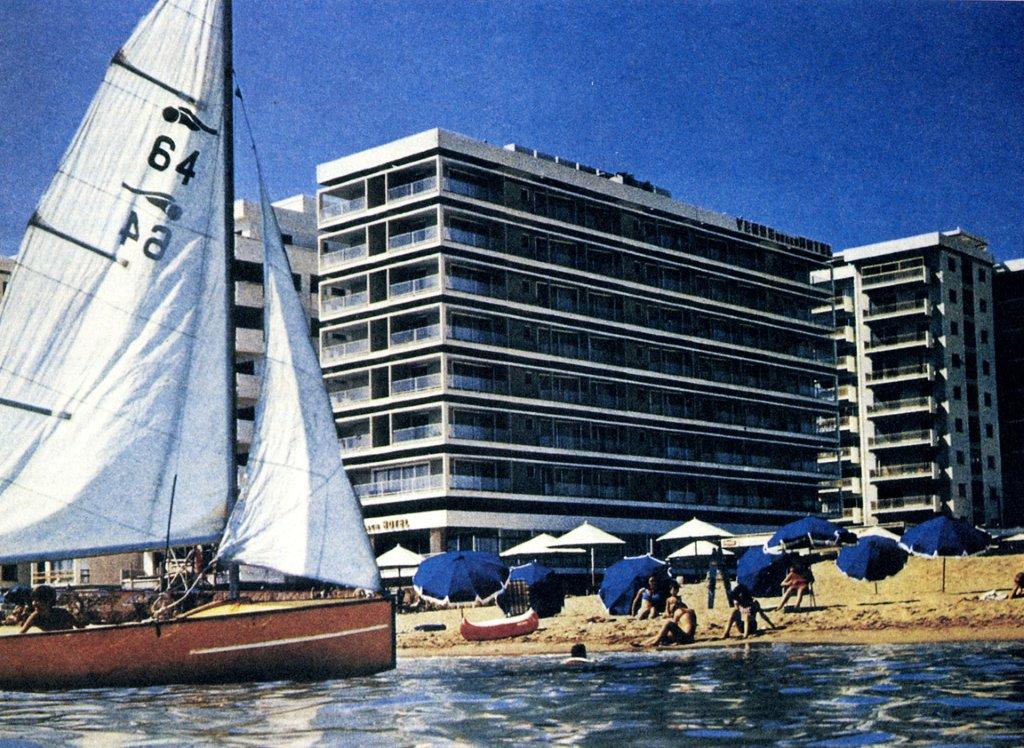

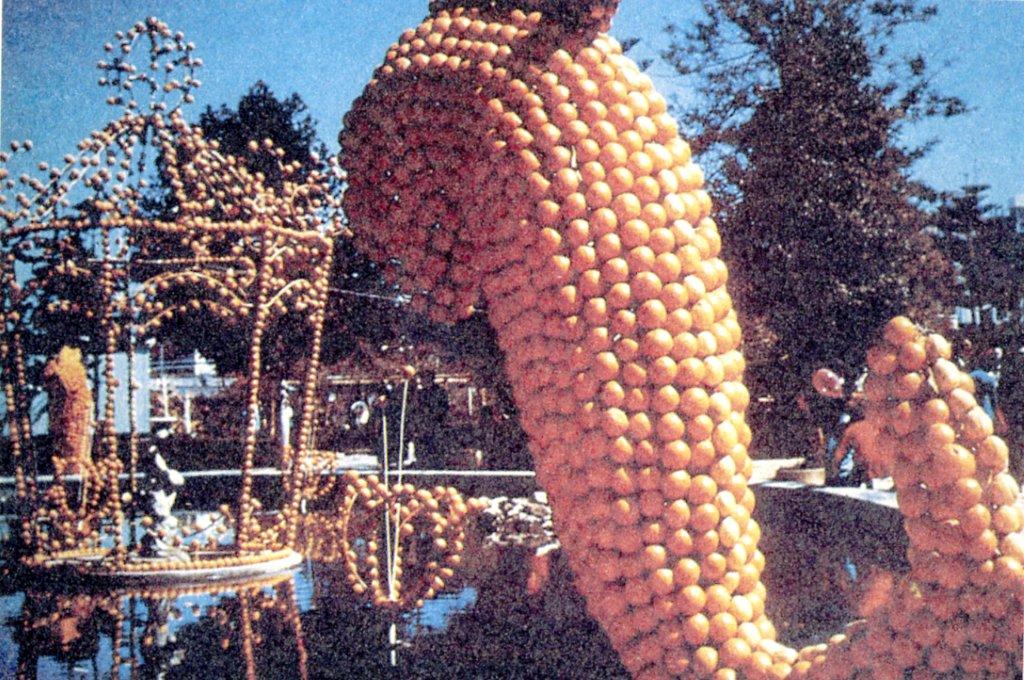

It had been a tourist boom town until it became suspended in a time warp. Its golden beaches and bustling hotels attracted the international jet-set and were graced by Hollywood stars, among them Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Sophia Loren, Raquel Welch, Paul Newman, Brigitte Bardot, and even the Swedish pop group Abba who first performed together at a Varosha hotel, long before they won the Eurovision Song Contest in 1974. Ironically, that was the same year Varosha was abandoned.

Varosha in its heyday. (Special thanks to Jimmy Freeman and Dinos Lordos for helping in the collection of these photographs)

Proposals to re-open Varosha to allow the return of its former inhabitants have featured prominently in all peace plans and confidence-building recommendations over the decades dating back to the 1970s. A 1984 UN Security Council resolution called for its handover to UN control and prohibited any attempt to resettle it by anyone other than those who were forced out.

Greek Cypriot hopes rose in 1993-94 with a UN-backed initiative to re-open Varosha in return for the re-opening of Nicosia’s mothballed airport — which is in the UN buffer zone – for use by both communities.

But Varosha continued to remain a symbol of the seeming intractability of the island’s frozen conflict, with many convinced Turkey has held it as a valuable bargaining chip to play only in the final stages of an overall settlement.

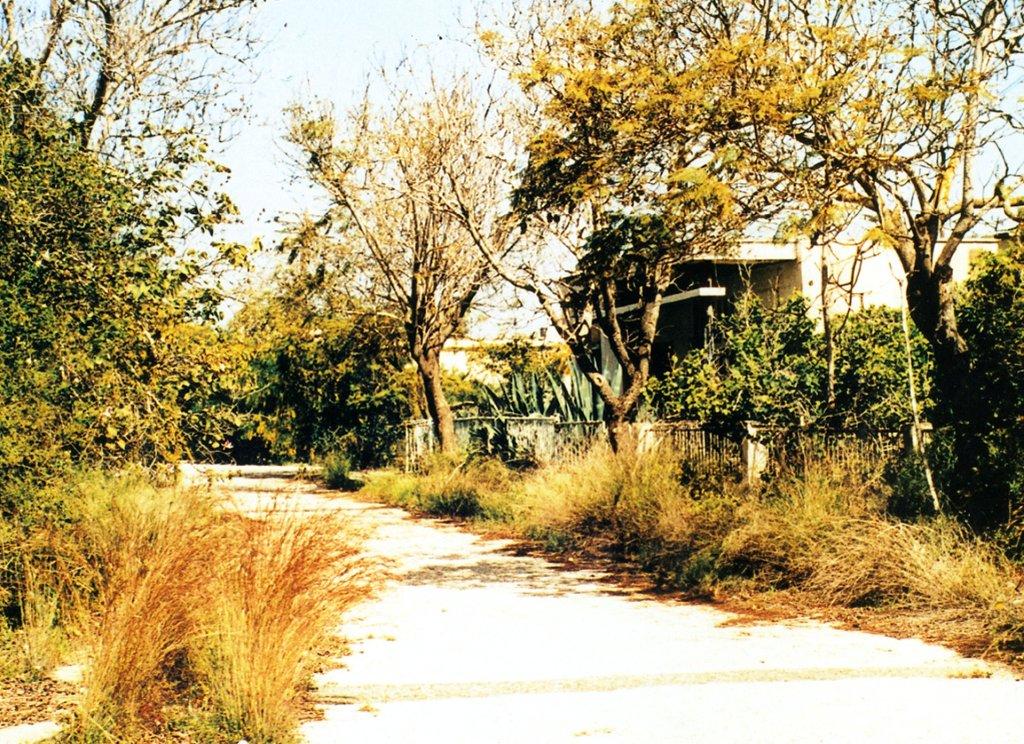

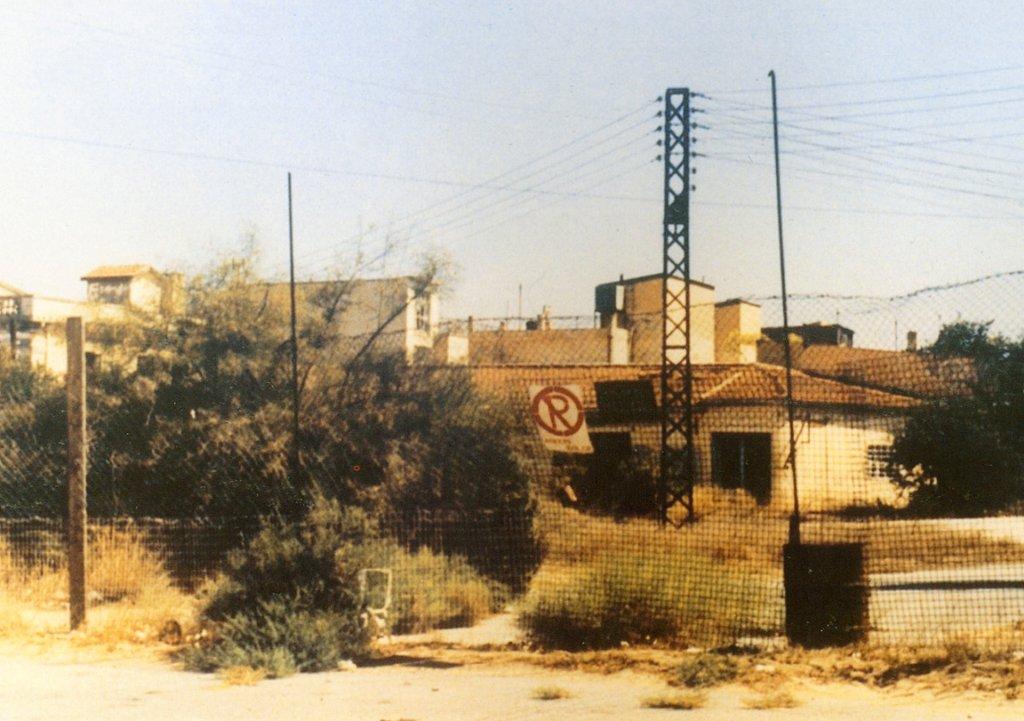

The seaside town long resembled a stage set for a post-apocalyptic movie in which a plague killed all the people, leaving only increasingly dilapidated and crumbling buildings standing with windows blown. Trees and shrubs grew in cracked and buckled roads roamed by stray cats and rats.

On paper, Greek Cypriot town planners had been preparing for Varosha’s return for years. The first step would have included a clean-up operation, inspection of buildings to determine if they could be made safe or needed demolishing, and the reconnection of water and electricity.

Returning Varosha to normal, it was estimated would have taken at least six or seven years. The cost of rebuilding the town was also difficult to estimate until experts were granted access to the six square kilometres it covers, but some economists suspected it would be at least €5bn but that was an early 21st century estimate and two more decades have passed since then.

Over the years, various groups devised plans to rebuild and re-inhabit Varosha, including the Famagusta Ecocity Project, which aimed at transforming it into a ‘smart’, ecologically friendly town. The project was formed by architects, engineers and ecologists, architects, engineers from both the island’s communities.

Varosha as it is today. (Special thanks to Jimmy Freeman and Dinos Lordos for helping in the collection and captioning of these photographs)

But every single plan for the return of Varosha was thwarted in 2020 when the Turkish side opened it up. After threatening for years, the area was opened to visitors on October 8 after some preliminary work was done along the seafront.

The Cyprus government immediately took up the issue with the EU and the UN Security Council.

The EU’s foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, said that reopening of the area, was “a serious violation”. “It will increase tensions and make it more difficult to reach an agreement on a particularly difficult situation for all of us in the Eastern Mediterranean,” he said.

The only hope of preventing further provocative actions and violations in Varosha would be through resuming the Cyprus talks, Famagusta mayor Simos Ioannou said.

Ioannou also said that the move, approved by Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan and announced by then Turkish Cypriot ‘prime minister’ Ersin Tatar in Turkey. Reportedly the announcement was made to aid Tatar in his election campaign, and indeed he was elected later in October as the new Turkish Cypriot leader, ousting the more moderate Mustafa Akinci who spoke out against opening Varosha.

Ioannou stressed that the move was taken, in part, to tank the Cyprus talks. He also stated that reopening the beach was a step towards the complete resettlement of Varosha. “They will proceed with opening larger areas of the beach, creating infrastructure and facilities while finding further excuses to keep on expanding,” Ioannou said.

He was not wrong. Despite the international condemnation, new EU and UN resolutions, which as usual, proved to be toothless against Ankara’s moves, the work on repairing parts of Varosha continued and thousands of visitors both from abroad and from the government-controlled areas have now visited the parts of the fenced off town that were upgraded. In the first two months alone, the number was put at 70,000.

Following a visit by Erdogan’s to Varosha in November 2020, the Turkish side even changed the name of the town’s main thoroughfare, Kennedy Avenue. The avenue, a symbol of the island’s erstwhile main tourist resort, was renamed after Semih Sancar, the chief of the general staff of Turkey from 1973 to 1978, including the 1974 Turkish invasion.

After he was elected, Tatar pledged to open “every square metre of the town”.

August 2020: Varosha: A Catch-22

Adding insult to injury, the Turkish side later invited Greek Cypriot refugees to claim their Varosha properties back through the Immovable Property Commission (IPC).

In October 2021, the Turkish Cypriot side began a new phase, clearing part of the area they had demilitarised for resettlement by Greek Cypriots who wish to reclaim their properties.

Barbed wire was removed and bulldozers and trucks carried out road repairs along the avenue that once showcased well-known Greek Cypriot shops and businesses.

The Turkish Cypriot side had announced earlier in 2021 that 3.5 per cent of Varosha, around five square kilometres, would be demilitarised and open for settlement on a pilot basis.

Populating Varosha is Verboten

Tatar said the reopening of Varosha for settlement was in line with international law and the north’s position on a two-state solution.

He said opening Varosha had brought many benefits for the Turkish Cypriots in terms of tourism, the economy but also politically.

Turkish Cypriot authorities expected 3,000 Greek Cypriots to file IPC applications for Varosha. By June 2021, they said they had received 344. This had risen to 500 by the end of 2023.

The Law Office of the Cyprus Republic was providing the government with legal advice on how to handle the issue. Attorney-general Giorgos Savvides said his office had set up a dedicated team to explore what legal measures, if any, Cyprus could take.

News broke later that a new part of the Golden Coast beach in Varosha, stretching to the Venus hotel, was almost ready. The beach was where Erdogan visited in November 2020, having a ‘picnic’ with Tatar and his wife.

The government repeatedly called on Varosha refugees not to turn to the IPC arguing this would help speed up Turkish plans for the fenced area and would be the last nail in the coffin of the Cyprus problem.

In July 2021, The UN Security Council condemned the Turkish side’s Varosha plan and called for the immediate reversal of their actions there.

“The Security Council expresses its deep regret regarding these unilateral actions that run contrary to its previous resolutions and statements,” it said.

“The Security Council calls for the immediate reversal of this course of action and the reversal of all steps taken on Varosha since October 2020.” The statement followed three days of haggling and three drafts.

The UN resolution was parroted a week or so later by the EU but Brussels stalled on taking any concrete action against Turkey, which ticked off the Greek Cypriot side. Two months later, the EU’s foreign ministers agreed to only consider “the possibility of measures” against those involved in activities in Varosha and offered mumblings of “solidarity” with Cyprus as they kicked the can down the road.

It was also considered insulting that the Commission wanted to “verify accusations by Cyprus” about what is going on in Varosha “as if Turkey and the Turkish Cypriot side has somehow been acting in secret instead of constantly bragging publicly about the changes going on there” as a CM editorial writer observed.

By February 2022, Tatar was bragging that the moniker ‘fenced-off Varosha’ “was no more” and the area was now open.

He said over 400,000 people had visited since its ‘opening’ and that hundreds of Famagusta refugees had now applied to the IPC. A month later, he announced that a marina would be built there as numerous reports continued to abound about the sale of Greek Cypriot hotels in Varosha.

Greek Cypriots sold Varosha properties because no solution in sight

Rumblings continued throughout 2022 and 2023 and into 2024 with the Turkish Cypriot side continuing to move forward and the Greek Cypriot side seemingly unable to do anything about it, and with a new negotiations process still in its infancy with the appointment of a new UN envoy only in January 2024.

In the same month, the UN Secretary-General’s report noted that in Varosha, “no steps were taken to address the call made by the Security Council in its resolution 2646 (2022) for the immediate reversal of the action taken since October 2020”.

An exasperated UNSG Antonio Guterres said: “I have repeatedly stressed the importance of the parties refraining from taking unilateral actions both in and adjacent to the buffer zone that could raise tensions, while also calling upon all parties to engage in dialogue to resolve their differences. I reiterate my concern over developments in the fenced-off area of Varosha and note that the position of the United Nations on Varosha remains unchanged.”