By Michael Theodoulou

At the time, the Annan plan of 2002 to 2004 was the UN’s most concerted and detailed attempt to reach a federal solution to the Cyprus problem. Named after the then UN secretary-general, Kofi Annan, it was supported by much of the international community. (See below for a summary of the plan’s provisions.)

There was strong backing in particular from the EU because Cyprus, represented internationally by the Greek Cypriots, was set to join the bloc in 2004. The EU was keen to see the island re-united first.

However, in twin referendums on 24 April 2004, Greek Cypriots overwhelmingly rejected the Annan plan, with 75.8 per cent voting against, while Turkish Cypriots accepted it, with 64.9 per cent in favour.

Annan presented a first version of his plan in November 2002 and a fifth and final version in March 2004. He had wanted the final text to emerge from negotiations between the two sides but, amid continuing deadlock, finalised the text himself. (In contrast, the 2015-16 drive for a settlement is wholly “Cypriot-owned”, with the UN acting solely as a facilitator.)

The Annan plan was opposed by the hardline veteran Turkish Cypriot leader, Rauf Denktash, but most Turkish Cypriots were enthusiastic. They hoped that a settlement would enable them to end their isolation by entering the EU alongside the Greek Cypriots in a reunited Cyprus.

Greece also supported the Annan plan, as did Turkey where the Justice and Development Party, AKP, won a landslide victory in November 2002 under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdogan. He had made Turkey’s membership of the EU a priority and knew accession was impossible while Turkey occupied northern Cyprus.

There was less incentive for the Greek Cypriots who, in April 2003, had already been guaranteed EU membership. President Tassos Papadopoulos was stridently opposed to the Annan plan and in a televised speech urged Greek Cypriots to reject it. He argued that it was tailored to suit Turkish interests at the expense of Greek Cypriot rights and would legalise the island’s de facto partition instead of reuniting it. Papadopoulos also calculated that Greek Cypriots could secure a more favourable Cyprus settlement once they were in the EU.

His speech prompted the communist party, Akel, a coalition partner in the Papadopoulos administration, to withdraw its earlier support for the UN proposals. Disy, the right-wing party then led by Nicos Anastasiades, backed the Annan plan, which was also supported by two former presidents, George Vassiliou and Glafcos Clerides.

Annan expressed dismay at the Greek Cypriot ‘no’ vote, as did Washington, London and Brussels. Cyprus entered the EU a week later on 1 May 2004, with only the Greek Cypriots enjoying the benefits of membership. The acquis communautaire, or body of EU law, was suspended in northern Cyprus pending the island’s reunification.

A Summary of the Annan Plan

The Annan plan proposed the establishment of the United Cyprus Republic, “an independent state in the form of an indissoluble partnership, with a federal government and two equal constituent states, the Greek Cypriot State and the Turkish Cypriot State”.

The structure of this bizonal, bicommunal federal republic structure would be based on the Swiss model.

The state would have a single international legal personality and single sovereignty. People would hold two citizenships: that of the common state and of the component state in which they lived. The latter would complement, not replace, Cypriot citizenship. Acquiring Cypriot citizenship would be covered by federal law, meaning that the federation controls immigration.

Any unilateral change to the state of affairs established by the agreement would be prohibited, in particular union of Cyprus in whole or in part with any other country or any form of partition or secession.

The federal government would be responsible for foreign policy and international relations, ensuring that Cyprus “can speak and act with one voice internationally and in the European Union”. It would also be responsible for Cypriot citizenship and issuing passports, immigration, antiquities, and some other matters.

The powers of the constituent states would consist of anything not governed by the common state. (In other words each would have a large degree of autonomy.) They would cooperate through agreements and constitutional laws that would ensure they did not infringe on each other’s powers and functions.

Governance

The new state would have a federal parliament made up of two houses. A Senate (upper house) would have 48 members with an equal number from each of the two communities while a Chamber of Deputies (lower house) was to have 48 members, no fewer of them 12 of them Turkish Cypriots. Decisions by parliament would require a simple majority vote of both houses to pass. There would also be separate legislatures in the two component states.

Executive power would be vested in a presidential council with six voting members. Parliament could also choose to add some non-voting members. No less than one third of the voting and non-voting members would come from each constituent state. No less than a third of members from each category would be Turkish Cypriots.

The presidential council would be elected on a single list by special majority in the Senate and approved by majority in the Chamber of Deputies for a five-year term. The presidential council would try to reach decisions by consensus. If this was not possible, then decisions would be taken by simple majority of members, provided this comprised at least one member from each constituent state. The council would elect a member from each constituent state to rotate every 20 months in office as its president and vice president.

The member hailing from the more populous constituent state would be the first president in each term. The foreign affairs minister and European affairs minister would not come from the same state.

A supreme court would have an equal number of judges from each constituent state and three non-Cypriot judges that would not be Greek, Turkish or British. The court would resolve disputes between states or between the federal government and the states.

Territory

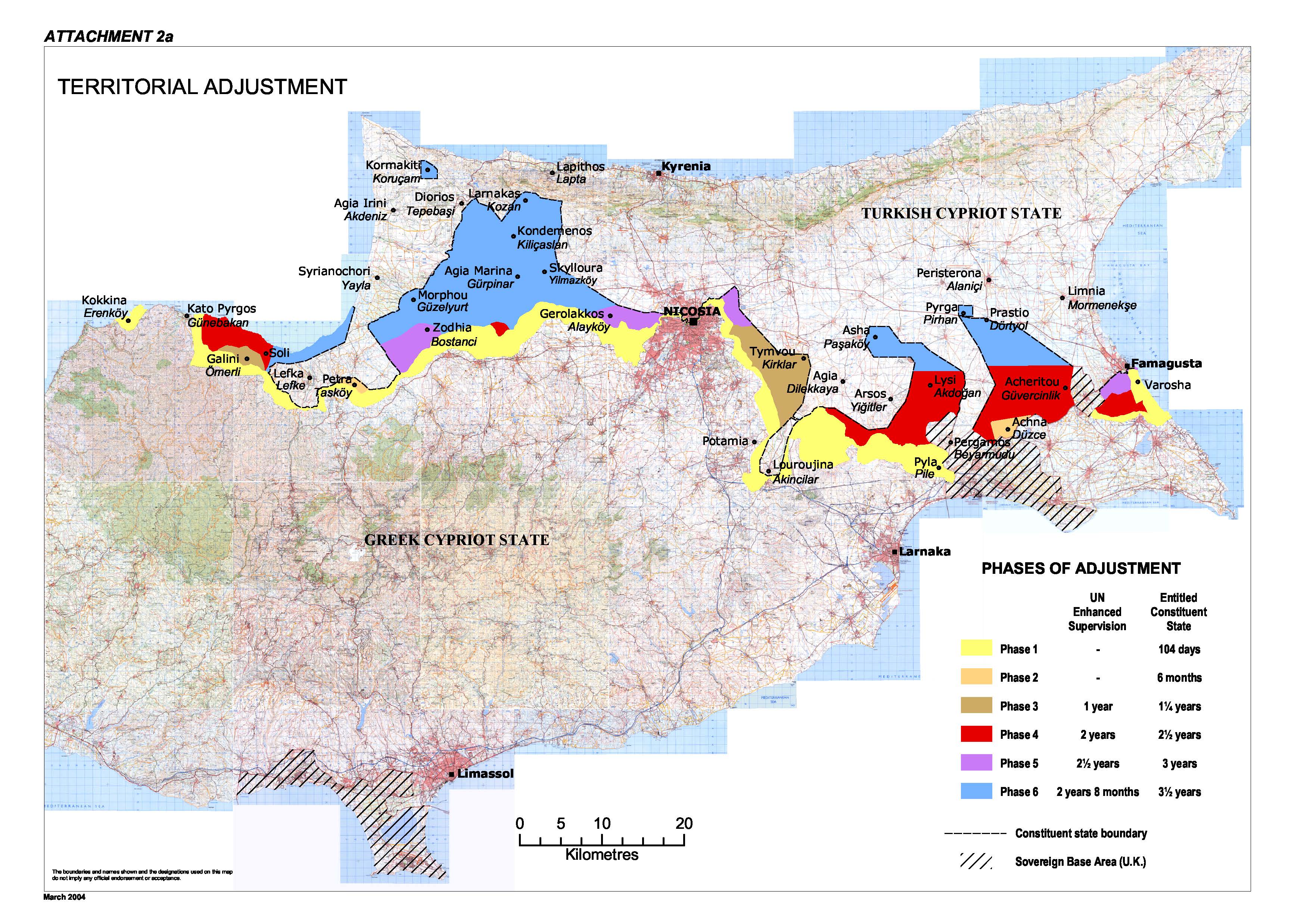

There would be significant territorial adjustments in favour of the Greek Cypriots. The Turkish Cypriots made up 18 per cent of the population at the time of the 1974 invasion but were left in control of 36.2 per cent of the island’s territory. Their territorial share would be reduced to 28.5 per cent. This would take place in six phases over a 42-month period, starting 104 days after the agreement came into force.

Property

The plan’s complex property provisions included restitution, compensation and exchange.

Greek Cypriots displaced in 1974 from territory to come under the control of their constituent state would get their properties back. Those not entitled to return to their homes would be paid compensation in guaranteed bonds based on market values at the time they were lost, adjusted to reflect the appreciation of property values since then.

All other dispossessed owners would have the right to reinstatement of one-third of the value and one-third of the area of their total property, and to receive compensation for the remainder.

Among other provisions, current users of properties originally owned by displaced Greek and Turkish Cypriots who have made “significant improvements” to a property could apply for its title, provided they paid for the value of the property in its original state. Cypriot citizens required to vacate property to be reinstated would not have to do so until adequate alternative accommodation was made available.

Security and Guarantees

The three 1960 Treaties of Establishment, Guarantee and Alliance would stay in place. Britain, Greece and Turkey would remain as guarantor powers.

In the event of the Annan plan’s acceptance, Britain said it would relinquish almost half of the 98 square miles of territory covered by its two sovereign military bases under the Treaty of Establishment. (Britain has since periodically reiterated its offer, most recently in September 2016.)

There would be a phased demilitarisation of Cyprus. All Cypriot security forces would be disbanded while Greece and Turkey would each be allowed to keep up to 6,000 troops in Cyprus until 2011. That would be reduced to 3,000 each by 2018 or earlier if Turkey joined the EU before that date.

After that, numbers would be scaled down to the original 950 Greek and 650 Turkish troops envisaged under the 1960 Treaty of Alliance. This would be reviewed every three years with the aim of an eventual total withdrawal of all Greek and Turkish forces.

You can read the full text of the Annan Plan here

If you have difficulty seeing maps or other parts of the Annan Plan, you can access its various sections separately here.