Archbishop Makarios III, a towering figure in Cyprus’ modern history, was president of Cyprus from August 16, 1960 until he died unexpectedly of a heart attack on 3 August, 1977, aged 63.

By Michael Theodoulou

During this period, Cyprus gained independence from Britain, suffered periods of intercommunal violence and, in 1974, was subjected to a Greek-inspired coup and a Turkish invasion that split the island.

A born survivor, Makarios defied several assassination attempts and was skilled at turning mistakes and even political disasters to his advantage.

For Greek Cypriots he was a respected, hugely popular and unifying figure. But the smaller Turkish Cypriot community saw the statesman-cleric as a champion of exclusively Greek Cypriot interests. By the time he began to address Turkish Cypriot concerns he had already lost their confidence.

Abroad, opinion was also mixed, although no-one doubted he was charismatic. The Times (London) carried a respectful obituary in 1977, describing Makarios as “a familiar and respected figure of the councils of the United Nations, the Commonwealth and of the Third World”. Sir Alec Douglas-Home, Britain’s prime minister from October 1963 to October 1964, was less impressed. He thought Makarios a “stinker of the first order”, according to a US diplomatic cable. Meanwhile, in another cable from 1964, a US state department official described Makarios as a “wolf in priest’s clothing”.

In some Washington circles, the statesman-cleric was nicknamed the “Castro of the Mediterranean”. He had appealed for Soviet support at the height of the Cold War, attempted to limit Nato’s influence in Cyprus, and played a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement. Makarios also enjoyed the support of Cyprus’ large communist party, Akel. What the US failed to appreciate was that his good relations with Moscow and the island’s communists were not ideological, but tactical.

The son of a shepherd, Makarios was born Michael Christodoulou Mouskos on August 13, 1913 in the Paphos district village of Panayia. Like many bright, hard-working children of poor Cypriots, he received his education from the independent, self-governing Greek Orthodox Church of Cyprus. At the age of 13, he became a novice at the celebrated Kykko monastery, emerging seven years later with a new clerical name – Makarios, meaning “the blessed”.

He took his divinity degree at the University of Athens in 1942, was ordained in 1946 and, with a scholarship from the World Council of Churches, studied theology and sociology at Massachusetts University in Boston for two years. He was elected bishop of Kition (Larnaca) in 1948 while he was still in the US.

In 1950 he was elected archbishop and head of the Cyprus Orthodox Church at the age of 37. It was the only elective job allowed under British rule and it meant that, like so many of his predecessors under foreign rule — notably that of the Ottomans — he also assumed the role of Ethnarch, or national leader.

Unsurprisingly, Britain viewed him as the political leader of a Greek Cypriot struggle to end its colonial rule. A four-year armed insurrection was launched in April 1955 by a right-wing underground guerilla organisation, Eoka (the National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters) led by General George Grivas, a Cypriot-born Greek army officer. The aim was not independence, but enosis (union) with Greece, which had mass Greek Cypriot support. The Eoka campaign was accompanied by wide-scale civil disobedience.

Makarios negotiated with the island’s British governor but when these talks proved fruitless, he was arrested for sedition in March 1956 and exiled to the Seychelles.

Many Greek Cypriots, meanwhile, quit the police force, either in solidarity with Eoka or because of intimidation by it. To help counter the insurgency, the colonial authorities replaced them with recruits from Turkish Cypriot community, which made up 18 per cent of the island’s population and preferred to stay under British rule.

This, together with Britain’s saying that Turkey should have a say in Cyprus’ future, led to Greek Cypriot accusations that Britain had adopted a policy of divide-and-rule.

While Grivas had forbidden harming Turkish Cypriots at the outset of the revolt, these Turkish Cypriot recruits inevitably bore the brunt of Eoka’s attacks on the police force. Inter-communal relations, peaceful until then, rapidly began to deteriorate.

With Turkish support, the Turkish Cypriots formed an underground guerrilla organisation, the Turkish Resistance Movement (TMT), whose declared aim was to prevent union with Greece, and began to call for taksim, (partition) and union with Turkey.

Makarios was released from the Seychelles in 1957 and, forbidden to return to Cyprus, went to Athens. By early 1959, he had reluctantly accepted a compromise agreement struck in talks between Greece, Turkey and Britain. It meant giving up enosis and accepting a qualified independence instead.

On his return to Cyprus in March 1959, he received a rapturous welcome from the Greek Cypriot community and in December that year was elected president of the future Republic of Cyprus. At the time, the BBC reported: “One of the first people to hail the archbishop’s success was the leader of the Turkish community, Dr Fazil Kucuk, once one of his bitterest rivals but now a staunch ally and soon-to-be vice-president.”

Cyprus became an independent state on 16 August, 1960. By treaty, Greece, Britain and Turkey became guarantor powers of the island’s independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity under the terms of Cyprus’ constitution, with rights to intervene militarily to uphold these. The following year, Makarios became one of the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement.

There were soon disagreements between the two communities over the workings of the complicated constitution, which was largely drawn up by Greece and Turkey, with little input from the islanders themselves. The trust and goodwill needed to make the new state’s power-sharing arrangements work had been eroded in the years leading up to independence.

In November 1963, Makarios proposed major amendments to the constitution, which he argued were necessary to make the state more functional after repeated deadlock in government. Turkey rejected the proposed changes, as did the Turkish Cypriots, who saw them as an attempt to undermine their political power in the Republic.

Violent clashes erupted in December 1963 and a dividing ‘green line’ was established in Nicosia. A UN peacekeeping force, Unficyp, was established in March 1964.

Large numbers of Turkish Cypriots began to move out of ethnically mixed areas into defended enclaves. Greek Cypriots alone were represented in the government, which was recognised internationally as the island’s only legitimate authority. Turkish Cypriots said they were forced out; Greek Cypriots said they left to set up their own parallel administration.

Violence continued periodically until 1967 when a major crisis nearly brought Greece and Turkey to war. After the Cyprus National Guard, commanded by Grivas and staffed with many mainland Greek officers, attacked Turkish Cypriots in and around two villages in the Kofinou area, Turkish warplanes buzzed Nicosia and Ankara threatened a military invention. Greece was forced to bring home thousands of its troops and to recall Grivas: this was, in effect, proof that Athens would not be able to come the aid of Greek Cypriots in any showdown with Turkey.

Makarios now accepted that enosis was not possible for as long as Turkey was determined to prevent it and declared that while union with Greece was desirable it was not feasible in the prevailing circumstances. Seeking a fresh mandate, he called elections for February 1968 and secured 96 per cent of the vote, trouncing his only rival, who ran on a platform for enosis. He then began to use his unique legitimacy as the Greek Cypriots’ spiritual and temporal leader to wean his community away from the notion of enosis: independence was the only practical solution.

Uniting with a Greece ruled by a right-wing military dictatorship that had seized power in a coup in Athens the previous year held little appeal for most Greek Cypriots, not least followers of the large communist party, Akel, whose support Makarios enjoyed. The Greek Cypriot economy had also improved significantly since independence and was delivering a better standard of living.

Now accepting that the Turkish Cypriots could not be sidelined, Makarios authorised Glafcos Clerides, president of the House of Representatives, to begin peace talks with their leader, Rauf Denktash, which began in mid-June, 1968.

But Makarios’ new policy of unfettered independence had put him at odds with the junta in Athens in 1970. In March that year he walked miraculously unscathed from the wreck of his helicopter when it was shot down in a junta-backed assassination attempt. With the failure of its silver bullet solution, the junta began a wider campaign against Makarios.

With the junta’s help, Grivas returned secretly to Cyprus in 1971 to prevent Makarios’ “betrayal of enosis” and founded Eoka B, a violent right-wing underground organisation committed to the archbishop’s overthrow. As attacks mounted on his supporters and police stations, Makarios established a loyal tactical police reserve in 1972. Many of its members were Makarios loyalists who had been in the original Eoka in the 1950s and used their experience against Eoka B. Surprise raids on its hideouts led to many arrests.

Makarios’ enemies in Athens were no match for him at the political level. He easily survived an ‘ecclesiastical coup’ in 1972 by three bishops (of Kyrenia, Kition and Paphos) who demanded that he resign as president, claiming that his political duties violated canon law. He had the three – all pro-enosis fanatics closely tied to the Greek junta – defrocked the following year and was returned unopposed for a third term as head of state.

Makarios became convinced that Greece was seeking to remove Cyprus as a source of friction with Turkey and irritant in Nato, if necessary by “double enosis” – the partition of the island between Greece and Turkey. When Grivas died of a heart attack in January 1974, Eoka B came more directly under the control of the Greek junta which, following a change of leadership the previous November, was even more hostile to Makarios.

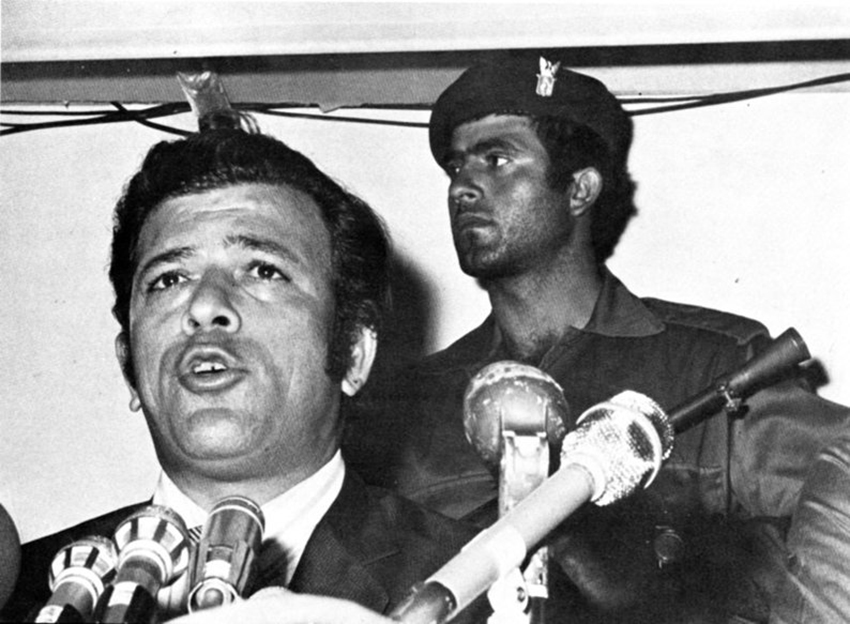

On July 3, 1974, he publicly accused the junta of using Greek officers in the National Guard to subvert his government and demanded that Athens withdraw 650 of them immediately. Instead, on 15 July, Greek officers in the National Guard, directed from Athens, launched a coup against Makarios aimed at enosis. The presidential palace came under heavy bombardment but he managed a lucky escape. He fled to Paphos and was then flown from RAF Akrotiri to safety in London.

The junta installed Nicos Sampson, an ex-Eoka killer who had taken part in attacks against the Turkish Cypriots in 1963 as president.

On 20 July – five days after the coup – Turkey invaded northern Cyprus, invoking its rights as a guarantor power. This brought the collapse of the coup three days later and with it the fall of Greece’s military dictatorship. Sampson had lasted just eight days as president. With the constitutional order restored, Glafcos Clerides, the respected president of the House of Representatives, became acting president of Cyprus until Makarios returned to a divided island in December 1974.

The UN Security Council unanimously passed a resolution calling on Turkey to withdraw its troops from Cyprus. Turkey refused, and continued to refuse despite repeated UN Security Council resolutions making the same demand over the following decades.

Within a month of the Turkish invasion, the ‘green line’ became a 180 km-long UN-controlled frontier slicing across the entire width of the island. Some 165,000 Greek Cypriots fled or were expelled from the north, and 45,000 Turkish Cypriots eventually moved in the opposite direction. The Turkish Cypriots, around one in five of the island’s population, were left holding 36 per cent of its territory with 35,000 Turkish troops enforcing the island’s de facto partition.

In February 1977, Makarios signed a High Level Agreement with the Turkish Cypriot leader, Rauf Denktash, which became the basis for future negotiations. It envisaged Cyprus re-united as a bi-communal federation. By accepting a federal solution, the Greek Cypriots in effect conceded that the bi-communal unitary state of 1960 was irretrievable. In future, Cyprus would need to consist of two units, with the Turkish Cypriots enjoying a large degree of autonomy.

Following Makarios’ death in August 1977, some 250,000 Greek Cypriot mourners filed past his coffin.