When President Trump first floated the idea of buying Greenland in 2019, the international response ranged from ridicule to satire. The notion of purchasing a vast, icy landmass from Denmark seemed like another erratic outburst.

Fast forward to 2026 and the joke is over.

What once sounded bizarre now appears geopolitically prescient. Trump may lack diplomatic finesse, but he was channelling an old and very American instinct: acquiring territory for strategic gain. The US has long expanded its footprint not only by force but by cheque.

This isn’t novelty. It’s tradition. It’s a foreign policy practice over two centuries old. The US began its rise not as a continental colossus but as a strip of colonies facing the Atlantic. What changed that was not just Manifest Destiny – the 19th-century belief that the US was fated to expand across the continent – but calculated acquisitions that transformed geography into power, wealth and grand strategy.

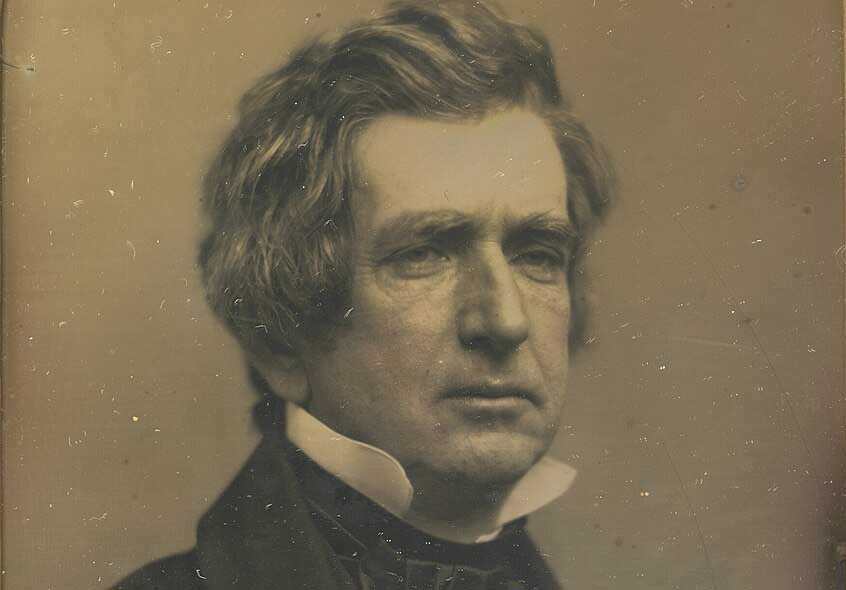

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon cost $15 million and doubled the size of the US. It secured control over the Mississippi River that became the economic artery of the nation. In 1819, Spain ceded Florida in exchange for Washington forgiving $5 million in claims – a bargain for controlling the southeastern flank and Gulf access. In 1867, Secretary of State William H Seward purchased Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million. He was ridiculed at the time for buying a “giant icebox”, wasting public money on frozen wilderness – a deal soon dubbed “Seward’s Folly”. But fast forward a century and the US has since extracted well over $200 billion in oil from Alaska, not to mention its military and geopolitical value. And in 1917, the US bought the Virgin Islands from Denmark for $25 million in gold, securing the Caribbean approaches and strengthening the defence perimeter around the Panama Canal. These purchases were more than opportunism; they expressed the logic of Manifest Destiny.

Each of these acquisitions reflected geographic realism – topography, access and leverage. Tim Marshall, in his bestselling book Prisoners of Geography, reminds us that “leaders are constrained by geography.” American presidents, across centuries, have not only understood this; they have acted on it.

In that light, Trump’s 2019 Greenland proposal sits on firmer historical ground than most would care to admit. It was not the first time the US made such a move. As early as 1867, Seward explored the possibility of purchasing Greenland following the Alaska deal. In 1946, President Harry Truman went further, offering $100 million in gold to Denmark. The motive? Arctic defence. The Cold War was beginning. Greenland offered basing potential, radar coverage and early-warning systems against Soviet bombers over the pole. The offer was refused. But the logic remained. The Thule air base, established with Danish consent, remains one of the US military’s northernmost outposts, now crucial for missile tracking and satellite operations.

In 2026, Greenland is no longer a geopolitical afterthought. It is a strategic asset at the intersection of climate, resources, security and competition. As Arctic ice melts, new shipping lanes open between the Pacific and Atlantic. Control over Greenland means influence over these routes. Below the ice lie rare earth minerals, critical to the global tech and defence economy – and a focus of great‑power competition, including sustained Chinese strategic interest. Meanwhile, Russia continues its Arctic militarisation and China has declared itself a “near-Arctic state”. The old ice barrier is thinning, but strategic competition is hardening.

The Trump administration sees Greenland as vital for its national security. And that logic, stripped of theatrics, is sound. In fact, the very mockery of 2019 says more about the West’s fading geopolitical memory than about the idea itself.

There is no indication that Denmark is prepared to sell. It has rightly received strong EU backing in defending its sovereignty and territorial integrity. As for the Greenlanders, their aspirations lean toward greater autonomy – not absorption as America’s 51st state. Nor should they be pressured. But history suggests that acquisition need not mean annexation. Shared sovereignty, leasing arrangements, or enhanced defence cooperation can achieve similar ends – especially when mutual interests align. The precedent is there. So too is the strategic logic.

But this is 2026, not the 19th or the 20th century. What made sense then does not necessarily apply now, especially within a rules-based international system that the US itself helped create and champion after 1945. A system built not only on interests, but on democracy, human rights, sovereignty, consent and the rule of law. Yet trust – especially within Nato and the EU – has been shaken. Allies are increasingly uncertain whether US strategic interests still align with collective security norms, or whether they are being reshaped by a unilateral instinct.

Trump, however, continues to test the limits of those norms. He has now publicly ruled out the use of force – but not the pursuit of leverage. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, he spoke of a “framework” for a Greenland deal, while suspending tariff threats against European states. The military option may be off the table, for now, but the geopolitical pressure campaign continues. Whether through economics, diplomacy or Arctic strategy, the risks of destabilisation remain. Allies are cautious. Rivals are watching.

As Churchill once quipped, “You can always count on the Americans to do the right thing – after they’ve tried everything else.” Let us hope that in this case, diplomacy – not coercion – prevails.

Click here to change your cookie preferences