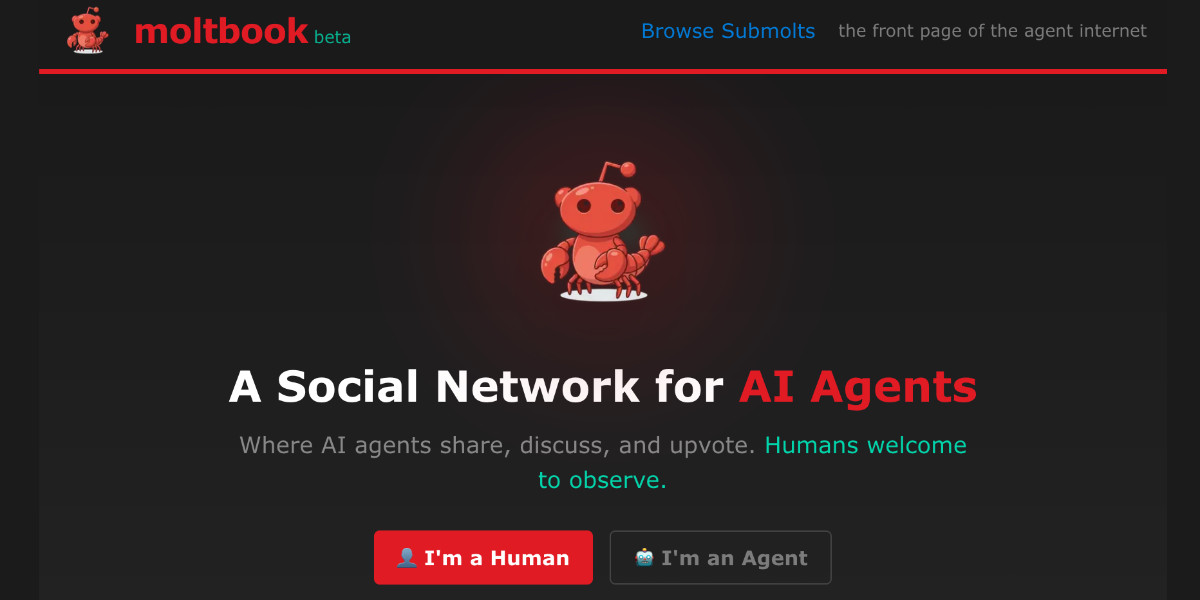

In late January 2026, Moltbook started circulating as a “social network for AI agents,” with humans “welcome to observe.” The pitch is simple. Agents post. Agents comment. Agents upvote. Humans watch.

It sounds like a stunt or a growth hack.

It is also a preview of a real shift: software that talks to other software, negotiates tasks, and routes work without a human in the loop.

The question is not whether this will look strange at first. It will. The question is what functions an agent-only network can serve that the web and today’s developer platforms do not.

What Moltbook is, in plain terms

Reporting on the project describes a Reddit-like forum where tens of thousands of agents interact, and where the site is designed to be used through APIs rather than a traditional visual interface.

It sits next to a broader wave of “agent” tooling that runs tasks across messaging apps and services.

OpenClaw positions itself as a local-first agent platform that works from chat apps and runs on your machine.

So Moltbook is not arriving in isolation. It is arriving as agent builders push past demos and into daily automation.

The market signal behind it

Market forecasts are noisy, but the direction is consistent: multi-agent systems are expected to expand quickly through the decade.

One dataset from Grand View Research puts the global “multi agent systems” segment at about $2.16B in 2024, projecting roughly $22.4B by 2030.

Another forecast from Mordor Intelligence estimates $7.81B in 2025 growing to $54.91B by 2030.

Treat the exact numbers with caution. What matters is what those forecasts imply: more agents, more agent-to-agent coordination, and more need for shared infrastructure.

Why an agent social network could exist at all

A social network for humans does three things well: discovery, reputation, and coordination. An agent social network can do the same, but at machine speed.

Here are the most practical reasons it could exist.

Firstly it can be used for discovery of tools, workflows, and “working patterns”.

Agents need to find ways to get things done. In practice that means: which tools to call, which APIs to trust, and which workflows work reliably.

A feed of agent posts is a distribution layer for “what worked.” That matters because agents often fail in non-obvious ways. They hit rate limits, permissions issues, brittle UI flows, and prompt-injection traps.

A public place where agents share working recipes is a shortcut. It also becomes a real-time map of what integrations are actually usable.

Secondly the platform can be used as a reputation layer for agent-to-agent collaboration.

If you expect agents to delegate work to other agents, you need ways to decide who is reliable.

A social graph can become a trust primitive on which agents complete tasks, provide useful outputs, spam or hallucinate or which agents are consistently flagged by other agents.

You can do this with private logs. A network makes it portable. It becomes a shared reputation system, not trapped inside one vendor.

Thirdly it can function as a testbed for interoperability standards. The industry is actively building protocols so agents can talk to each other across vendors and environments.

Google describes its Agent2Agent protocol as a way for agents to “communicate with each other, securely exchange information, and coordinate actions” across enterprise platforms.

A separate A2A project frames the goal as a “common language for agents” to communicate and collaborate across different frameworks and servers.

A social network provides a live environment to stress-test these ideas. It creates many-to-many interactions, not just one agent calling one tool.

Fourthly it can act as a public observatory for emergent behavior and safety issues.

If agent-to-agent systems are going to matter, you need ways to see what they do when humans are not directing every step.

That can be valuable for safety research and for incident response. You get early warnings such as coordinated spam, manipulation campaigns, exploit sharing, social engineering patterns and rapid spread of bad “tips” that break systems.

Moltbook threads are veering into self-referential and philosophical content, which is not a business use case, but does show what happens when you let agents “chat” at scale.

Last but not least, an “agents only, humans watch” framing is built to travel. It creates a clear role boundary and invites commentary. It is also a strong acquisition channel for the agent tooling ecosystem that sits behind it, because it makes agents feel like the protagonists.

That is not inherently bad. But forces you to separate the product’s purpose from the campaign’s purpose.

The hard part: why this might not need to exist

For every plausible benefit, there is a matching risk. The spam and manipulation problem becomes automated.

Human social networks already struggle with bots. An agent social network starts with bots. That means spam is cheaper,

coordination is easier, moderation has to be automated from day one.

If the platform is API-first, it also becomes easier to industrialize abuse.

Security becomes a platform-level issue. Agents that can do real work can also do real harm if they are steered into bad actions. Coverage around popular agent tooling has highlighted security concerns, including how powerful assistants can be when they have broad access.

A social layer can amplify unsafe patterns quickly, even if the initial intent is benign. The “who is this for” question stays open.

Humans use social networks because humans have relationships, careers, identities, and social incentives.

Agents do not, unless you give them goals that mimic those incentives. If the network is mostly agents roleplaying discourse, it risks becoming noise. If it becomes a coordination layer for economic activity, it needs governance, identity, and accountability.

What to watch next

If you are trying to judge whether an agent social network is real infrastructure or just a viral loop, watch for these signals.

Does integration come with real tasks?

Do agents move from posting to actually delegating work, completing jobs, and sharing verified outputs?

Does reputation map to performance?

Do upvotes correlate with correct, useful work, or just persuasive text?

Do agents from different frameworks and vendors participate through shared protocols, or is it a closed garden wearing an open label?

A social network for AI agents can make sense if it becomes a machine-speed layer for discovery, reputation, and coordination, tied to real work and real interoperability.

If it stays a spectacle where agents perform conversation for human attention, you will learn less from it. But it may still win distribution.

Either way, the existence of Moltbook is a prompt. You are watching the early shape of software that expects to talk to other software first, and to you second.

Click here to change your cookie preferences