The latest series of works by Zenon Jepras reflect his lockdown. THEO PANAYIDES meets a man who puts his success down to luck and compulsion

Can we say self-deprecating? Zenon Jepras’ website (www.zenonart.co.uk/) playfully describes him as “publicity shy”, and also offers this glowing endorsement: “Zenon Jepras was born in 1969 in Wales to Greek parents from Cyprus and Corfu. Consequently, he’s the most famous Welsh-Greek artist in Cyprus”. I suppose it’s something, after 25 years in the game.

He’s low-key, sitting outside the Alpha CK Gallery in Nicosia where his latest exhibition – titled Ithakas – is about to go up; smallish, bald, bespectacled, and so softly spoken that I strain to catch what he’s saying, even on a quiet side street. He was “small and fast” – that was his secret – in his days as a teenage rugby star. (This was in Wales, where rugby is a religion.) His views are firm but quietly expressed, his sense of humour sly. “Maybe I’m regarded as quite geeky,” he offers mildly when I ask what he’s like in a group of friends; “Lots of useless information, that kind of thing.” Had the story of his life been filmed in the 60s (before he was born, alas), he might’ve been played by a young Donald Pleasence.

Then there’s the art – and of course that’s a whole different matter. It’s not just that he’s very successful, Ithakas being his 23rd solo exhibition in 25 years. (That self-deprecating bio is misleading in another way too: he’s not ‘in Cyprus’, having lived all his life in the UK.) It’s also the art itself, which is as in-your-face and exuberant as the man himself appears – at least in interview mode – to be mild-mannered and self-effacing.

“I like populating large canvases with lots of characters doing various things – sometimes quite nonsensical,” is how he puts it. His striking, pop-surrealist art, strongly influenced by German Expressionist painters like Max Beckmann and Otto Dix, is figurative but also narrative, in the sense that a story’s being told; his people always seem to be caught in mid-action. They’re fleshy, thick-limbed, often sensual, sometimes grotesque. They jostle and crowd against each other, a reminder that all the paintings in Ithakas were done during lockdown – indeed ‘The Rule of Six’ is explicitly a riff on the UK government’s Covid guidance, except that the figures in the piece (blissfully enmeshed in a kind of conga line or human centipede) “are very much not socially distancing”.

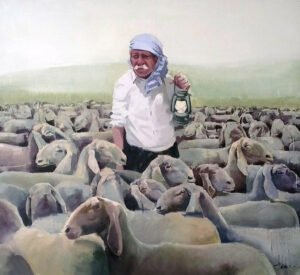

- Christos Theodorides

- Christos Theodorides

- Christos Theodorides

- Christos Theodorides

The background in that work is a kind of emetic, mustard-yellow floral wallpaper; the background to ‘The Moths of Ithaka’ is a profusion of pink flamingos. Vivid use of colour is a Jepras trademark: his colours aren’t representational but “theoretical and emotional”, meaning he paints things with whatever colour fits best, not what it ‘should’ be in real life. Zany humour is another trademark: the crowd on board a small boat in ‘Odysseus Unbound’ includes a seagull, a macaque monkey, a grinning skeleton and a man taking a shower. His intricate style recalls graphic novels, or the jam-packed creative anarchy of Mad magazine; no surprise that he started out, back in childhood, drawing caricatures – “satirical paintings of world leaders” – before becoming an omnivorous reader of art books, making his own childish copies of what he discovered in Matisse and Picasso.

As a kid, “I didn’t know art history was a thing,” he admits with a chuckle. “I don’t think I was taken to a gallery – well, took myself to a gallery – till I was about 16”. His background is firmly working-class: his mum cleaned hotels, his dad was admittedly not a fish-and-chip-shop owner – like most UK Cypriots of that generation – but an accountant whose clients were predominantly fish-and-chip-shop owners, plus a few barbers and hoteliers. It made for a certain culture shock when Zenon decamped to London to study physics at UCL, finding himself among English public schoolboys (not many girls doing physics in those days) after the “fairly average” Welsh state school of his childhood.

It sounds like a happy but slightly disconnected childhood, with himself as the smallest, youngest member of a somewhat overwhelming family. His mum (now unfortunately stricken with dementia) “was a very, very strong character and a dynamo, a non-stop person,” he recalls affectionately; his late father also sounds quite dynamic, a serious man who founded and ran a Greek school in Cardiff and always spoke English to his youngest son. Zenon has two half-brothers, but they’re 15 and 10 years older. Easy to imagine the boy poring over his art books, not unhappy or unloved – not at all – yet also wishing he could somehow convince others to take his calling as seriously as he took it himself. “I mean, I do have an interest in maths and physics, even now,” he shrugs, recalling the UCL degree he tried (in vain) to complete so as not to disappoint the family. “But it was quite obvious from the age of 10, if they were looking. My parents should’ve known that I was on my way.”

That said, his parents had a point. Having dropped out of physics, Zenon purposely applied to the best art school in the country, “the most difficult art college to get into – which was Glasgow School of Art, at the time”. One presumes he felt a need to prove to himself that he wasn’t deluded about having talent; but talent, it turns out, isn’t everything. “‘You’re here because you’re all very talented’,” he recalls the head of department at Glasgow telling the new intake – about 100 students – at the introductory meeting. “‘It’s very difficult to get into this school. But only two of you will still be engaged as a painter, as an artist, one year after leaving our school’… Those were the statistics at the time.” The school was insanely rigorous, hours and hours of technical training; students arrived in the morning and often didn’t leave till midnight. Yet 98 per cent of the best young artists in Britain were statistically fated to give up just a few months after completing their degree. The art world is ruthless.

So why do some artists make it? Luck, for a start, “a big stroke of luck early on,” as Zenon says. “And that’s quite often in the form of a big collector coming in, taking a shine to your work in your first show and buying up most of it, which then creates a wave of interest… I know artists who are 10 times more talented than I am, naturally gifted, who didn’t get that break, that stroke of luck, and so they left it.” His link to Cyprus has been useful in this regard, allowing a way in to a smaller market (his folks moved back in the early 90s; he’s been visiting every couple of months ever since) – and indeed most of his solo exhibitions have been here, including the first one in 1996 when a big collector (media magnate Nicos Pattichis) duly took a shine to his work and helped him on his way. That show was called Odysseia, based on The Odyssey – and Ithakas, too, is based on Homer, albeit with an assist from Cavafy: a full-circle journey, echoing Odysseus’ own journey.

Luck, we repeat, is important. But there’s something else too, something more important than luck. You need – how to put this nicely? – to be a little bit nuts. “It’s a compulsion,” explains Zenon softly. “It’s not something I can stop doing for any length of time… So, even if I wasn’t making a living out of it, I’d still be doing it.”

The compulsion has nothing to do with making money. It even has nothing to do with ‘self-expression’, that weasel word so beloved of well-meaning profs. It’s not a compulsion to show the work and receive applause or acclaim. It’s purely a compulsion to paint, just because… well, because it’s a compulsion. “It’s not about recognition or selling, it’s about doing it. When I do these paintings, as soon as they’re done and I’m satisfied – and I don’t stop till I’m totally satisfied with every little square inch of it – it’s out the door, out of the way, in fact it gets rolled up, I’m quite merciless. And I’m on to the next one.”

He tends to think in series (like the series of paintings in Ithakas), spends a few months doing sketches and preparatory work, will sometimes succumb to “white-canvas terror” for a while – the fear of getting started, basically – but then he plunges in, smearing an oily rag on the canvas “to spoil the surface – so the spell is broken, if you like – then I’ll work into the drawing with charcoal, then there are stages where I’ll paint very loosely in quite liquid paint”. Each canvas takes between 10 days and three weeks to complete – “then I’m always looking to the next one, and the next one. So you can see how that turns into a compulsion”.

One may wonder how he ever gets out of the studio – an impression he likes to reinforce, in his mild-mannered way. “I live with my wife and my daughter, who’s now 16, and they’re both very spontaneous and social,” offers Zenon wryly. “They are a pair of party chicks who like to go out and socialise a lot – which is great, because that gets me out of my shell… Left to my own devices, I’d probably live in my studio and not come out much.” His wife was an artist herself – they met in Lempa in 1991, at the art college run by Stass Paraskos – but describes herself as a “lapsed artist” (she still works in the art world, curating and installing exhibitions). “With her,” he explains matter-of-factly, “it wasn’t a compulsion”. She loves painting, and will offer valuable advice on his own work – but could (and can) live without it, whereas Zenon can’t. “I’m afraid my daughter is already showing signs,” he adds lightly, shaking his head at the prospect. “Very regrettable signs that I’m trying to suppress, without any luck. She’s probably much more gifted at her age than I was. But, again, I don’t know if she has that same urge to do it all the time.” That said, she’s being rather teenage about the whole thing (“Dad,” she quipped recently, “you literally watch paint dry for a living”), so hopefully not.

This, in a nutshell, is the Zenon Jepras persona: the quiet man, forever overshadowed by louder, more outgoing family members, ruled by an ungovernable urge to keep producing vibrant, exuberant, larger-than-life art. I presume it’s quite close to the truth – but it also edges close to a certain stereotype, the Van Gogh epigone whose crazed, sumptuous style functions as a kind of lifeline, almost a kind of exorcism, and that’s not him at all.

“I’m not a loner,” he insists. “I’m not – absolutely not! – any kind of artist that needs to be miserable, or in some despondent state in order to work, to be inspired. Quite the opposite: I have to be happy, I have to be cheery, I have to be generally in a good frame of mind”. Recall that he played rugby at school, “a hooker, right in the middle of the scrum” – and in fact he was great at it (he even played for Cardiff Boys, the town team), and in fact he loved hanging out with his teammates, and they all knew about his artistic endeavours and wished him well. He’s not detached from the world, lost in some fey artistic bubble; “I’m not shy to be political”. I mention what a weird year it’s been, with the pandemic, and he sounds quite reproving: “Well, ‘weird’ doesn’t really cover it, does it? It’s been catastrophic!”. (His politics are left-ish, as you might expect from an artist in the leafy London neighbourhood of Herne Hill.) He doesn’t actually have to be dragged out from the studio by his wife and daughter, indeed he’s something of a regular when it comes to after-art drinks; the photo next to his self-deprecating website bio shows him raising a bottle of Keo.

The art reflects the man in being clever, humorous, and (perhaps) more virtuosic than poetic. Zenon doesn’t really come across as the lyrical type; he’s too knowing, too mordant. There’s a lot of the classicist about him, even beyond his affection for classical texts. He reads a lot, having recently switched to fiction after years of nothing but non-fiction (at the moment it’s Drive Your Plough Over the Bones of the Dead by Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk), and buys physical books over Kindle. He dabbles in Instagram (only for work), but anyone who posts pictures of delicious meals or lovely holidays gets an immediate unfollow. You might say he’s a craftsman, lost in his work, put off by all things flashy, drawn to old-fashioned virtues like self-deprecation, wit and technical excellence.

Actually, it’s even more specific than that: he’s a problem solver. “It’s a process of problem-solving and decision-making,” says Zenon Jepras, to describe how his art gets created. “And problems get solved.” The geeky side, the interest in maths and physics, the methodical way he goes about things, even the compulsion to keep working – like a crossword or Sudoku fan spending hours doing puzzle after puzzle – all speak to an interest in the moment itself, the craft, the problem, beyond any overarching theme or destination. As with all Ithakas, it’s about the journey.

Ithakas continues at the Alpha CK art gallery in Nicosia until June 30

Click here to change your cookie preferences