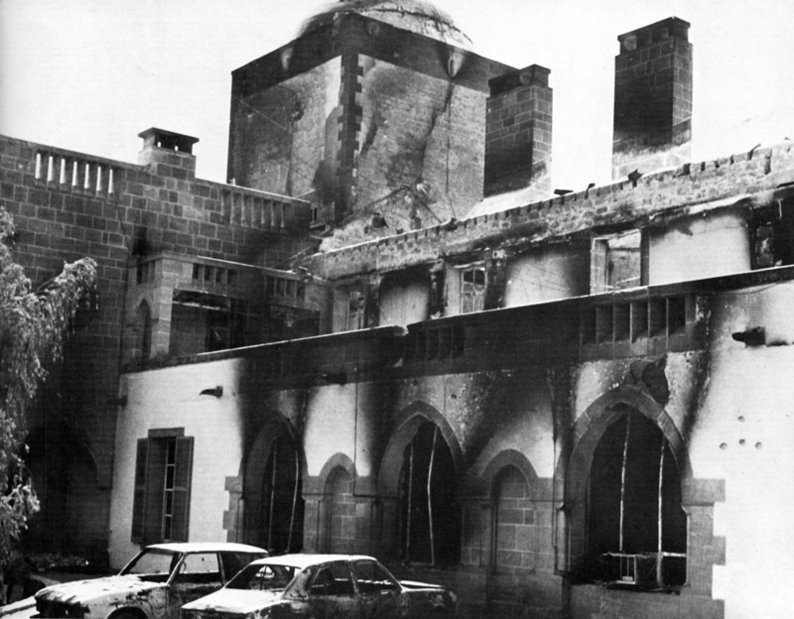

Sirens are sounded in the Republic of Cyprus every year at the exact time President Makarios was overthrown on July 15, 1974. Makarios was receiving some Greek Egyptian children at the presidential palace when all hell broke loose, and they had to be led away to safety after which he made his escape to Paphos.

From Paphos Makarios was saved by a British helicopter and taken to Akrotiri from where he was flown to Malta and then to the UK. On arrival in London he set a humorous tone: “they tried to kill me, as you see I am alive but tell me, were my obituaries good?” he asked reporters before heading for the Dorchester Hotel in Mayfair. Whatever criticisms people had or still have of Makarios he had a great sense of humour.

Makarios was a month shy of his sixty first birthday and had been president of RoC since independence in 1960 and archbishop since 1950. He was behind the campaign against the British to unite Cyprus with Greece (Enosis) that began with a plebiscite among Greek Cypriots in 1950 and an armed struggle by Eoka – acronym for nationalist organisation of Cypriot fighters – between 1955-1960. It was commanded by colonel George Grivas a Greek Cypriot officer in the Greek army who had been recruited for the task by the Greek government and who was a constant thorn in the side of Makarios’ pragmatic approach to Enosis later on.

Eoka and the church were an IRA-Sinn Féin type duo but after independence Makarios pulled away from the ultimate goal when he announced in elegant Greek that while Enosis was desirable it was not feasible. This was primarily because of Turkish opposition, but also for a variety of Byzantine complexities including the nature of the regime in Greece, which had become a military dictatorship in 1967, and because he relished his unique status as head of church and state.

The 1970s, however, were a very difficult decade for Makarios and Cyprus and it is now possible to look at the events of July 15, 1974 in perspective with the benefit of hindsight.

It is said that the first draft of history is contained in reports by journalists of events as they occur. The second draft is when enough time has passed for the glimmerings of cause and effect to be faintly discernible on the horizon even to an historian manqué like myself. The short interregnum between the overthrow of president Makarios on July 15, 1974 and the resignation of Nicos Sampson as president a week later belies the fact that it was the culmination of long standing divisions in the Greek Cypriot body politic that came to a head on that fateful day.

Makarios fought his first presidential election in 1960 against John Clerides a lawyer politician who had support both from the left and the right but not the overwhelming majority of Greek Cypriots who voted the archbishop to be their first president by a convincing majority.

Makarios was returned unopposed next time round but in the 1968 presidential election he was challenged by a pro Enosis candidate, Dr Takis Evdokas, an unknown American trained psychiatrist who stood in order to embarrass Makarios over his alleged betrayal of Enosis. Makarios won hands down, but the fact of an election marked the beginning of a campaign to remove him from power.

In 1970 his helicopter was shot down as it left the Archbishopric within the walled city of Nicosia. It is not easy to disentangle fact from fiction about the downing of the president’s helicopter. Very shortly after the shooting, a former minister of interior was removed from a plane as it was taxing to take off from Nicosia international airport. He was later found shot dead in mysterious circumstances. He was not the sort of guy to fall for any kind of sting operation but standing back years after the event it is clear the gloves were off, and RoC stayed on the brink of internecine war until July 15, 1974.

In the meantime Grivas returned to Cyprus and set up a replica of the original Eoka that fought for Enosis against the British, rebranded this time as Eoka B, ironically to fight for Enosis against Makarios who founded the movement.

Makarios branded Eoka B as a rebel terrorist organisation and created his own military force to face them down. The danger of internecine fighting loomed larger and larger when in 1973, apropos of nothing ecclesiastical, there was an attempt to unfrock Makarios as archbishop by the three metropolitan bishops of Cyprus on the ground that as a head of the church he could not hold political office. This sounds reasonable in retrospect but was absurd at the time given he had been president since 1960.

He managed to see the unruly bishops off by calling a supreme synod of neighbouring orthodox churches that ruled he could only be unfrocked by twelve of his peers. Makarios survived and the three wayward bishops were replaced.

It is, however, now the law in Cyprus that an archbishop cannot become president, not least because in an ostensibly religious country like RoC, an archbishop has an unfair advantage among voters over rival candidates owing to his venerable status as head of the church. The change in the law has not stopped the church from meddling in politics but at least the separation of church and state is now enshrined in constitutional practice.

General Grivas died in January 1974 and matters came to a head in early July when Makarios decided to expel the Greek army officers in control of the Greek Cypriot national guard. On being asked on British television in an interview set in an idyllic setting in the garden of his palace, what he would do if the officers refused, he smiled and said: “I shall disband the national guard and they can stay here as tourists.”

In hindsight that was not very funny at all, even though I must confess I laughed out aloud when I heard him say it as he seemed to be doing his best to promote Cyprus as a tourist destination even as he felt the invisible hand from Athens seeking his extinction.

Alper Ali Riza is a queen’s counsel in the UK and a retired part-time judge

Click here to change your cookie preferences