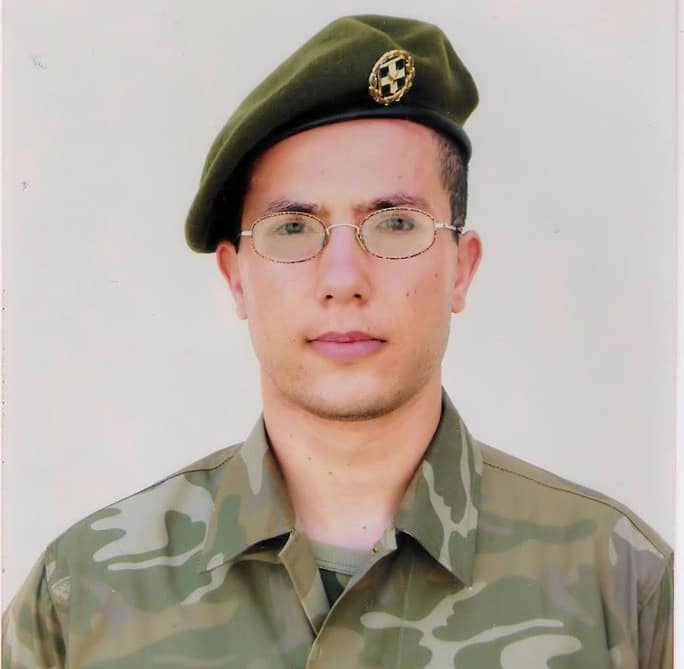

In one of the founders of Nicosia’s American Medical Centre, THEO PANAYIDES finds an assertive and dynamic medic looking to the future from the healing environment of his clinic

Maybe it’s because I can only see the eyes. I always prefer being unmasked when doing interviews, for obvious reasons, but we are after all in a hospital – the American Medical Center (AMC), on the outskirts of Nicosia – and it wouldn’t do for its co-founder Dr Marinos Soteriou (he’s also director of the Cardiothoracic Surgery Department) to be flouting Covid rules in public, so here we are. All I can see are his eyes above the surgical mask – and I notice heavy bags under those eyes. Has he not been sleeping well?

“Well,” he replies in perfect English, honed through decades abroad including 14 years in the US, “I think this specialty requires that you’re available 24/7… So, inevitably, the phone will ring multiple times every evening – so sometimes you get a good night’s sleep, sometimes you don’t.” I’d assumed the doctors on the night shift would take care of patients, even those requiring surgery – but no, it’s apparently quite common for Marinos to be roused late at night and brought in to operate, wiping the sleep from his eyes. “There are real emergencies that can’t wait till morning, and they have to be operated on… If somebody has a ruptured aneurysm, or other medical emergencies that have to be addressed on the spot – these people have the so-called ‘golden hour’, if you intervene within that time period they have far better results,” he explains. “It’s like firefighting.”

He must live quite close by, I venture, conjuring up a mental image of a groggy doctor speeding down the highway, trying to make it to the OR before the hour is up.

“Actually I don’t live ‘close by’, I live on the premises of the hospital. My house is attached to the building! As they say, the farmer’s shadow is the best fertiliser.”

Marinos is obviously all-in where the AMC is concerned – and has been since 1999, when he started the business (then known as the American Heart Institute) with Dr Christos Christou, and especially since 2011 when they moved to these stunning new premises, unlike any in Cyprus and indeed (he claims) probably in Europe. The main entrance is impressive enough, all glass walls and bubbling fountains, the structure reaching out to enfold visitors like the wing of a plane (or mother hen), then the waiting area is leafy and high-ceilinged – an indoor garden, as he puts it – like the lobby of a five-star hotel. None of this is accidental, Marinos being an architecture buff with a fondness for Mies van der Rohe who was closely involved in the design of the hospital.

It’s worth dwelling on these details – both because the AMC is his brainchild, his legacy (“something [to be] left behind when we’re gone,” as he puts it), and because they help to illustrate what kind of person Dr Marinos Soteriou is, a big-picture type with a visionary bent and a faith in technology. He is, by his own account, assertive and dynamic, which apparently is a surgeon thing: different fields of medicine tend to attract different personality traits, and the surgeons tend to be the most aggressive – because “you invade somebody, literally, and you’re not supposed to do that in Nature. God didn’t make us to be opened and closed,” he adds with dry humour, “and making incisions, and finding organs and fixing them. That was not the idea, I think”.

His sense of humour is deadpan in general (though it could be that he’s smiling broadly behind the mask; masks are a nuisance), the humour of a man who’s used to his jokes not always being understood by those around him. Marinos has a quietly assured, smartest-guy-in-the-room vibe. It’s no surprise that he’s always wanted to be a doctor, since his childhood days as an accountant’s son in Limassol – nor is it really a surprise that what tipped the balance to becoming a heart surgeon was the “major breakthrough” that occurred in 1982 when the first artificial heart was implanted by Dr William DeVries in Utah. It made a huge impression on Marinos, then a 23-year-old medical student at the University of Cologne – and of course it was a technological breakthrough as much as a medical one but the line between the two is rapidly blurring, especially these days.

Like the AMC building itself, with its Bauhaus designs and carbon filters – there’s even a helipad! – he tends to embrace the new and different; he looks to the future. “We’re now going through the Fourth Industrial Revolution,” he tells me. “There’s a whole bunch of new technologies coming up that are going to change completely the way we deliver healthcare.” Marinos rattles off a list, “starting from stem cells, mRNA technology, wearable devices, artificial intelligence, telemedicine… We’re now at the sub-cellular level of DNA, where we can diagnose things way ahead of them happening”.

Pretty soon, it’s going to be possible to identify those prone to cancers long before they actually develop the cancer – even from “the minute they’re born”, for some diseases: “You’re going to get a drop of blood, analyse their DNA and know what’s going to happen a few years down the line. We’re going to have technology to splice – we do have technology to splice – that DNA and put a specific gene in there, if something’s missing”. Medicine is changing beyond recognition; even Covid had a silver lining, having enabled mRNA vaccines to emerge after decades of research, “and I think that’s going to change medicine, for sure”. Haemophiliacs missing a clotting protein will be jabbed with the mRNA coding for that protein, cancer patients injected with a vaccine that’ll recognise the spike on the cancer cell, “and the cancer is treated”. The sky’s the limit.

It’s a little strange to be sitting in a hospital – however magnificent – in Nicosia talking about this stuff; wouldn’t he rather be in New York, doing cutting-edge medicine? After all, one of Marinos’ favourite books, a book he gave to his children as a present (he has twin girls, now in their 20s; his wife is also a doctor, and works at the AMC), is Jonathan Livingston Seagull, the early-70s bestseller that’s all about self-improvement, the fable of a seagull who works to become the best possible seagull. “The idea is that everyone else is playing but [Jonathan] is perfecting his technique of how to fish and how to fly higher and so on, and even though he was a seagull – he wasn’t an eagle or anything – he was always pushing himself to the next level”. One might say it’s a surgeon’s kind of book, fitting in with the high-flying, competitive characters one tends to find in the profession.

“It’s important to try to improve, as much as you can,” he declares. “Try to learn as much as you can, and try to use these things to create good.” The eyes seem to flash with the import of what he’s saying: “Every human being should try somehow to contribute, to some extent, to the wellbeing of the whole species”.

One might assume that someone so laser-focused would be restless here, obsessed with a need to ‘fly higher’ – but Marinos Soteriou isn’t entirely that kind of person. “I think I’m more in the multi-tasker category,” he observes mildly – and that’s the point with a big-picture type, they’re not just focused on one thing. In Isaiah Berlin’s famous division of people into foxes and hedgehogs (where “a fox knows many things, but a hedgehog knows one big thing”), Marinos seems like the latter but is actually the former. He’ll happily go on tangents, like for instance the first-ever documented ‘pros and cons’ list (Darwin apparently made one, to decide whether or not to get married), and he also talks of things outside the narrow realm of medicine: climate change, financial turmoil, the state of the world in general.

A big-picture person can discern the smaller (but real) satisfactions of being a good clinician in a small place, not quite an eagle but still a successful seagull – though he’ll also see the flaws and limitations of that place: we speak here of Gesy, our national health system, of which Marinos is a frequent and outspoken critic. “We have been deceived,” his business partner Dr Christou told this newspaper in January 2012, a few months after the hospital opened, meaning they’d embarked on the project with the assurance that a health system would be in place by the time they’d finished. Since then, however, a health system has indeed been launched – and the AMC, unusually among private hospitals, isn’t part of it. “As they say,” notes Marinos in his dry way, “be careful what you wish for.”

There isn’t space here to enumerate all the problems he finds in the system – but the basic point is that everyone’s cashing in, making for a gravy train that’s heading straight for a cliff edge (though it’ll surely be kept on the rails until the next election, at least). Patients are getting tons of tests, there’s a “circus of unnecessary testing”; most GPs – far from being the gatekeepers of the system – have become playmakers passing people on, functioning “like a concierge service” and making money for nothing; public hospitals are endlessly subsidised; worst of all, “everyone’s trying to do more and more procedures” (i.e. operations), so seriously ill patients – who might linger in a hospital bed – are discouraged in favour of quick, in-and-out cases. “A lot of them die,” he adds soberly.

And what of his own cherished project? On the one hand, many hospitals offering an inferior product to the AMC are doing just as well, if not better: “There’s a lot of wheeling and dealing inside the healthcare system”. On the other, medicine is changing in ways that go far beyond Cyprus – and he’s well placed to take advantage. A big-picture type can see all sides. I’m a bit surprised, given his earlier enthusiasm for mRNA, when we talk about autoimmune diseases and he wonders if the vaccines will lead to a spike in such cases, as some are predicting (“We hope and pray that this was the right thing to do, and most likely it was. But the fat lady didn’t sing yet”) – but I shouldn’t have been surprised. He’s able to take a step back, indeed that’s his strength: a big-picture type goes beyond narrow politics, whether it’s Covid or Gesy.

Meanwhile Dr Marinos Soteriou keeps working, performing 200-300 operations a year as well as a leading role in the running of a big private hospital. His nights are interrupted, his days often frantic; he’ll sometimes skip lunch altogether. He has no other passions to speak of, except maybe architecture – and has absolutely no plans to retire anytime soon. “My ambition is probably to die with my boots on.” And his scalpel in his hand? “If I can,” he replies with another dry chuckle.

“I think we all strive for a bit of recognition, and being at a certain level in the pack.” Like Jonathan Seagull, we all – obviously including the ambitious, heart-surgeon types among us – yearn to be the best seagull we can be, “and we all, in our own weird twisted way, want to achieve that somehow. Some people more, some people less… Everyone is striving to have a position in the group.”

Not everyone wants to be the alpha in the pack, though.

“Well, you don’t have to be the alpha,” he replies with a smile (or it’s probably a smile; masks are a nuisance). “You just have to be someone who’s content with what you’ve achieved.” He, I assume, feels that contentment, despite – or because of – doing too much, and not getting enough sleep most of the time. You can see it in his eyes.

Click here to change your cookie preferences