Some cynical clever dick at the Home Office has devised a scheme to deter asylum seekers

By Alper Ali Riza

Rwanda is perceived as the most refugee-repellant country in the world. Its 2003 constitution was conceived in the wake the genocide of the Tutsi in 1993 that was orchestrated by unworthy leaders that decimated the lives of one million Rwandans, while the international community looked the other way.

Some cynical clever dick at the UK interior ministry (Home Office) has now devised a scheme whereby asylum seekers looking to enter the UK unlawfully in small boats across the Channel would be flown to Rwanda for their claims to be examined and if made good to be resettled there as refugees.

Rwanda seems an eccentric choice, but actually it is precisely because of its reputation that it was chosen by Britain to outsource its obligations under the Refugee Convention.

High ranking civil servants have been racking their brains at the Home Office to find an answer to unwelcome refugees ever since Britain regained control of her borders after Brexit at the end of 2020.

Getting a partnership agreement with Rwanda to fulfil Britain’s obligations under international refugee law may be a cynical manipulation of the minimalist protection refugees have under international but is it lawful?

Under the 1951 Refugee Convention the obligation to refugees is not to send them back to the borders of the country they fled for fear of persecution. Strictly speaking, there is no obligation under the Convention to examine a claim to refugee status nor to grant asylum.

According to the UN a refugee does not become a refugee because of recognition but is recognised because he is a refugee, so the British authorities can lawfully assume, without deciding, a person is a refugee and transport him to Rwanda.

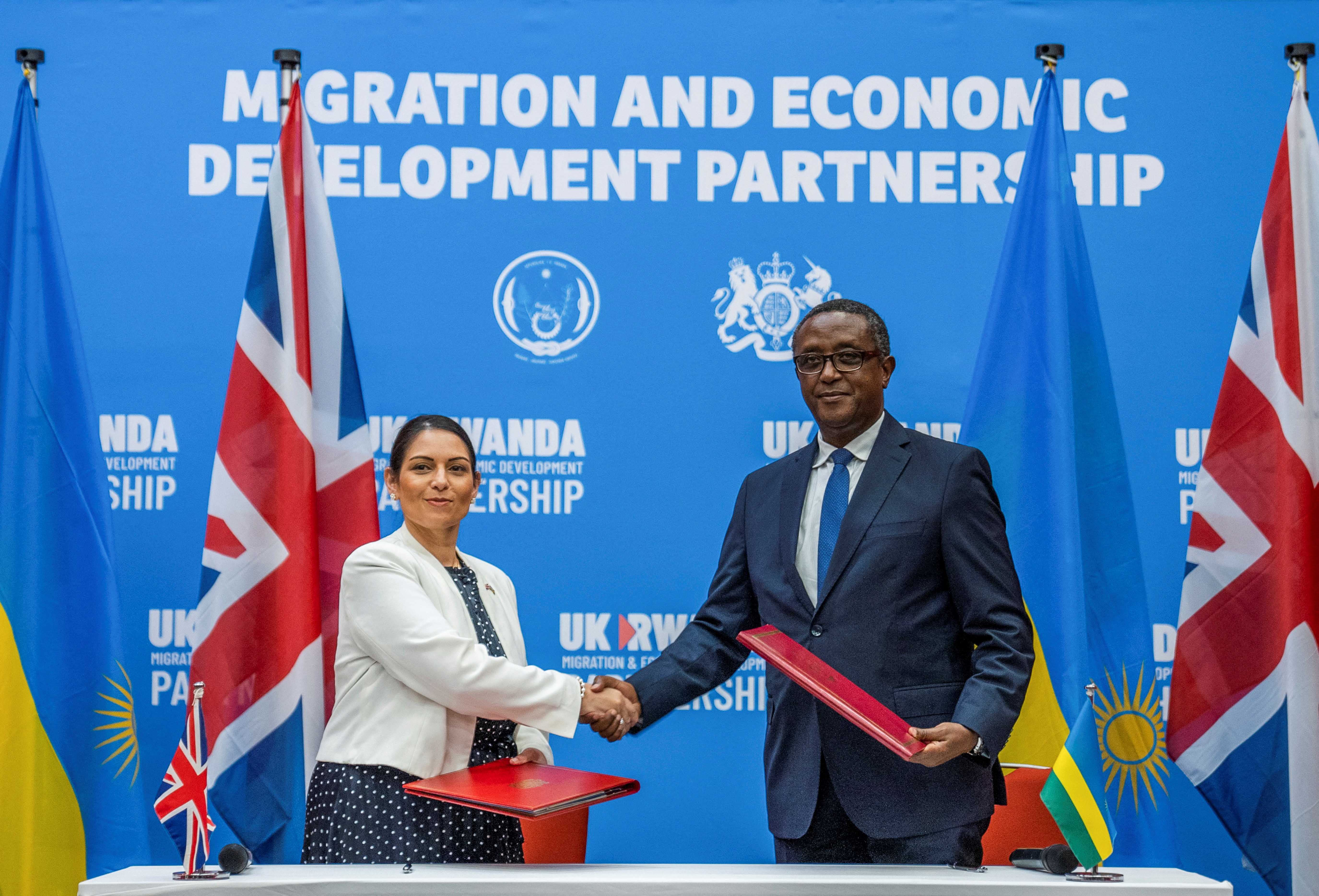

The guiding principle at the Home Office is that just because a policy is arbitrary or cynical or unprincipled does not mean that it is wrong. The idea behind the partnership agreement signed by Britain’s interior minister and the Rwandan government last week is that although the pact with Rwanda is cynical – Faustian even – the litmus test is whether it would be effective in stemming the flow of unwelcome refugees arriving across the Channel.

The calculation is that no refugee is going to pay thousands of pounds to people-smugglers to be brought to Britain if he knows that on arrival he would promptly be flown to Rwanda – the plan is that not many refugees will actually be transported there since the idea is zero-tolerance of irregular arrivals.

The policy may be lawful under the Refugee Convention and it may even stem the flow but is it compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights? The whole policy could be challenged on the ground that it is cruel and inhuman to fly refugees thousands of miles to a country with a dubious human rights reputation in the hope and expectation that that would deter arrivals of unwelcome refugees in Britain.

Also, if Britain gets away with outsourcing her obligations under refugee law it will set a bad example for other European countries to partner up with unsavoury regimes around the world in order to deter refugee arrivals.

Last year, Cyprus and Malta took in many more refugees per 10,000 of their population than all the other European countries including Britain. Who could blame these two small island states if they followed Britain’s example and sought similar partnership agreements with Rwanda or some other willing partner?

The ethical criticism of Britain for outsourcing her obligations under Refugee law to Rwanda is not that she is doing anything contrary to the letter of the Refugee Convention but rather that she is mocking refugees fleeing persecution. As the plight of Ukrainian refugee shows, when contemplating the predicament of refugees never forget the old adage: there but for the grace of God go I!

The problem of irregular movement of refugees far away from the countries from which they flee persecution is that they cannot justify to their hosts in Europe and North America that they should be offered refuge there rather than closer to home. The UN needs to address this problem because if a country like Britain is prepared to stoop so low as to outsource its humanitarian obligations to Rwanda, the working of the Refugee Convention is in grave and urgent need of reform.

In 1988 we persuaded the English Court of Appeal that the acquisition of refugee status was given to persons fleeing persecution in their own country who reach the borders of an adjacent state seeking protection, provided they have good reason to flee – a test that was both subjective and objective.

Unfortunately, the House of Lords – the UK Supreme Court – reversed the Court of Appeal holding that the test was not whether one was fleeing one’s country for good reason but whether there was a reasonable likelihood of persecution on return.

I believe this erroneous approach has been the source of most of the problems caused by the irregular movement of refugees in Britain and Europe the last thirty years because it divorced recognition of refugee status on arrival from the idea of fleeing persecution in the sense of escaping across borders to neighbouring countries.

The test adopted by the UK Supreme Court shifted the centre of gravity from the requirement that one needed to be in the process of fleeing to the borders of another adjacent state, to the later stage that deals with the circumstances in which states are entitled to withdraw refugee status under the cessation provisions of the Refugee Convention.

The time is ripe for a restatement of refugee law by the UNHCR to make it clear that international refugee protection does not offer a choice of place of refuge either to fleeing refugees or to the states to which they flee.

Alper Ali Riza is a queen’s counsel in the UK and a retired part time judge

Click here to change your cookie preferences