In a military man and academic who appears to be a ‘posh Brit’ THEO PANAYIDES finds a fascinating history of stories that reflect on the history of Cyprus and led their teller to be decorated by numerous governments

Names flit and hover in the study of Jo Carby-Hall’s Nicosia home, memories of those he’s encountered in the course of his nine decades. (He turns 90 in a few months.) Some of the people were central to his life, like his mother Nina (née Caruana) – a striking woman gazing out from a black-and-white photo in the living room – or his father Daniel, an architect by profession and a brigadier in the Territorial Army. Others are more tangential, turning up en passant, often just a name and a quick thumbnail sketch, sparking a story or else prompted by another story.

People like his great-grandmother Mathilde Gerard, for instance, daughter of the French ambassador in what was then Smyrna, who fell in love with a banker named Cababe in Cyprus – he may have been Lebanese – and ran away from home at 19, hired a Turkish fisherman’s boat to get her to Paphos, then rode a mule to Nicosia to be with the man of her life. People like Donald MacKinnon, a moral philosopher who was Jo’s supervisor at Aberdeen University (he later became Professor of Divinity at Cambridge; he was a brilliant mind) who spoke in a mournful, lugubrious tone, like a bell tolling, and was nowhere to be seen when Jo knocked on the door of his office one day: “Come innn, come innn, come innn,” intoned the prof, finally revealed to be hiding under his desk. “It’s all right Mr Carby-Hall, come in, I am sheltering from the evils of this world.” People like Ahmed, an Egyptian PhD student at the University of Hull (where Jo has been based since 1970) who was brutally beaten in a racist attack just a couple of months ago. Quick mention of mysterious people like Dr Siman – a dentist who was “known throughout the Middle East” – and Vahan Gregorian, a distant relative in Paris who “wanted to write a book about me”.

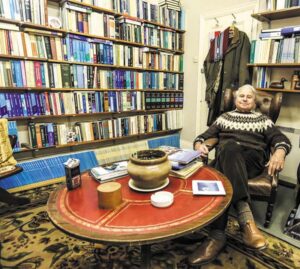

Jo in his office in Hull

Jo’s been around, even more than most people his age. He holds three doctorates and four state orders. He’s been awarded the Knight, Officer and Commander of the Cross grades of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland – but also has a necklace of beads from Kalabit tribesmen in Borneo, who knew him as ‘The Man From the Sky’. (We’ll get to this later.) Some of the people whose names haunt the study are famous. Jo has encountered both Makarios and Nicos Sampson, for instance – the former at lavish parties at the home of his aunt Militsa Stavrinidou, whose family owned Eleftheria newspaper back in the day. As for Sampson… well, he shot Jo in the leg, and in fact the bullet remains embedded in the bone even now. We’ll get to this later too.

There’s another, quite important person in the house with us, who’s also incidentally planning to write a book about him. That would be Diane Ryland, a law researcher at the University of Leeds (Jo himself is now director of international legal research at Hull) who first met him 28 years ago, while he was married to his ex-wife Hilary, and much later became his partner. Diane makes us coffee – her first-ever stab at Cypriot coffee – and sits in the next room, listening attentively. He refers to her often (“Diane knows him,” he’ll add when mentioning someone) and she, in turn, will sometimes get up and come into the study to add a caveat or jog his memory; the couple are a team, indeed they’ve been cooped up together for two years (they live in Beverley, near Hull) in Full Covid mode, not even going to the supermarket. This is their first trip since before the pandemic, here to check on the house that belonged to Jo’s parents.

He’s not exactly what you might expect. The name sounds so British – yet in fact his dad was the only British element, marrying into a cosmopolitan Cyprus-based family that descended from Mathilde Gerard and her Lebanese banker to a Maltese shipowner named Caruana, Jo’s maternal grandfather and a colourful figure in his own right. (He owned three ships and always gave a concert – playing the violin himself – when one of his ships came through Larnaca; then he went bankrupt, and ended up working for the exiled king of Hejaz.) Jo’s English, even now, has the clipped cadences of the posh Brit but also an accent with more than a trace of the Middle East; he speaks five languages, having been born in Lydda (now Lod) in what was then Palestine, and imbibed Arabic as his childhood tongue. At home with his mother, “when we were angry we spoke French to each other,” he jokes, “when we were very happy we spoke Greek. And my father didn’t speak a word of anything but English. He’d always say ‘What’s wrong with English?’.”

That said, Jo was seldom ‘at home’ growing up. The house has been theirs for generations, indeed his family used to own the whole street, 13 plots of land (this particular house, built on two of those plots, was torn down in 2000 and rebuilt in the original style) – yet he himself never lived in Cyprus as a child, having been a boarder since the age of five (!) when his dad was transferred to Egypt. Three idyllic years as the only little boy in a girls’ school in Jerusalem (“I wish I knew then what I know now,” he adds with well-practiced glee) were followed by six challenging years at a French Jesuit school in Lyon which was “hell,” he recalls. “They drummed into you things… I was fed with Hell, Purgatory.” The priests warned that even going to an Orthodox church was an act of sacrilege, which would surely send their young charge to Hell. “I did not like it – but I became a fanatic,” says Jo. “At the age of 14 I was a fanatic Catholic, they put me in a seminary because I had ‘the vocation’… When my parents learned that, I was immediately sent to an English school!”

Jo’s mother

He finished his schooling at King’s School Sherborne – but it’s worth going back a bit, to consider his time at the Jesuit place. The boy was smart enough to see that the priests couldn’t answer his questions, and surely cosmopolitan enough to be wary of the monolithic Catholic doctrine – yet his reaction wasn’t to become cynical, or rebellious; it was to become a fanatic. At the risk of assuming too much, that little detail hints at two salient traits in Jo Carby-Hall. The first is that he’s amiable, gregarious, happier to get along with people than chafe against them. The second is that he’s an idealist.

The amiable side is no surprise in a man who’s had to ingratiate himself with strangers since the age of five. He’s friendly and extremely courteous, without being stuffy or formal; his name is Joseph but “everyone calls me Jo… All my students call me Jo”. He makes a point of not being flamboyant. “I’m a simple man,” he tells me. “We all have our ambitions – but my ambitions are quiet ones, behind the scenes.” Yet he’s also had (and continues to have, at nearly 90) a remarkable two-pronged career – actually three-pronged, if you add his work as honorary consul of Poland – in both academia and soldiering. “We’re a military family,” he offers by way of explanation. “I’ve been in all three services.” Jo spent three years as an RAF pilot, 10 years in the Royal Artillery (the unfortunate side effect being that he’s almost deaf in his left ear) and has been in the Royal Naval Reserve since 1968. “We were fighting for democracy. I believe in democracy,” he explains, showing a glimpse of the idealistic side.

That’s his retort when I ask about fighting in Borneo – back in the 60s, when the Brits were called in to resist Indonesian dictator Sukarno’s attempted incursions in Malaysia. “I was there for a whole year, living in the jungle… I even had a pet monkey.” He was the FOO, Forward Observation Officer, meaning that he went up in a helicopter – hence the Kalabit calling him ‘The Man From the Sky’ – to locate the enemy, send rough co-ordinates to the gunners 20 miles away (flying through high mountains, with the jungle below so dense it looked “like cauliflower”), “and then drop as quickly as possible,” he recalls with a laugh, “so as not to get shot by your own people! Then you go up again, to see if you’ve hit the target.” Jo had a young wife back home and no real business risking death on the other side of the world, especially as a reservist – but it didn’t matter. Like he says, they were fighting for democracy.

Being an idealist doesn’t mean being a fanatic, at least not since his Jesuit phase. “I believe in democracy. I don’t believe in Communism,” he declares – this time apropos of joining the Intelligence service during the Cold War, specifically the JSIU (Joint Services Interrogation Unit), renting out castles with suitably hellish dungeons in order to train SAS soldiers to resist Soviet interrogation. “I’m not a Communist – [but] I’m not an ultra-conservative either. I’m sort of…” He gestures to indicate ‘in the middle’. “Slightly to the right, perhaps, but not much.” That said, he’s seen active service in several wars – Yemen, Afghanistan, Iraq, in the north Atlantic during the Cold War – though he’s only been wounded once, by the aforementioned Nicos Sampson who shot him in the leg outside the Magic Palace cinema in Nicosia, in 1956 or thereabouts. Jo was in RAF uniform but off duty, waiting for his girlfriend; Sampson fired a shot from about 15 feet, fortunately ricocheting off the columns outside the cinema, then ran away. “Coward!” yelled our hero, clutching his wound, as the Eoka man fled the scene.

That unwanted encounter with Sampson represents his soldierly side – but the meetings with Makarios are a lot more revealing of Jo’s true nature. Aunt Militsa would always invite her nephew to her glitzy shindigs “because I was good company for the party. And this is what I hated about colonialism – the English were here, and the Greeks were here”. His job, in other words, was to bring the two sides together – a task well suited to his cosmopolitan nature, his brand of convivial idealism, even rhyming with his later academic work as a specialist in Labour Law, trying to forge consensus between warring stakeholders. The profusion of names hovering in the room is oddly appropriate: a lifetime’s worth of people, and Jo – a people person – embraces them all.

“I’ll always fight for the underdog,” he says. “I’ve always done that.” In his quiet way, he’s extremely active – even now, at nearly 90, though he’s slowed down a bit and suffers from glaucoma, and his hearing is shot from all that artillery fire. His work ethic is remarkable; he’ll work till one in the morning and be up at six. “I publish a lot, I’ve had two books published last year” – and articles, and chapters in books – but he’ll also just talk to people, and help when he can. He’s the kind who’ll ask nurses about their families, and chat to security guards about their legal problems. He was the one who accompanied Ahmed (the aforementioned Egyptian PhD student) to hospital, and insisted there was evidence of GBH when the cops were reluctant to act – though ‘insisted’ is perhaps a bit strong. His style is calm, respectful; he’s not the type to try to bulldoze people.

Diane suddenly bursts into the room, concerned that he’s being too modest. “You are kind, considerate,” she blurts out, with the air of someone going a little too far but unable to stop herself. “You spell your case out. People listen to Jo,” she says, turning to me. “I mean, you probably think I’m biased – but I think I’m absolutely blessed. This gentleman has changed my life. I’m absolutely blessed – and I didn’t mean to be saying this,” she adds, catching her voice as it wavers a little. “You’re speaking to someone who is very, very special. He treats everyone as if whoever he’s with is the most important person, and the time he devotes to everyone is unbelievable.”

Jo says nothing, looking red in the face as if flushed with emotion. The time he’s devoted to me is also impressive; we’ve been talking – he’s been talking – for over two hours, going from theatres of war to mad academics to the old vanished Cyprus – though of course we’ve barely scratched the surface, how could it be otherwise? I say goodbye, still a little dazed and trying to make sense of it all. 90 years compressed into two hours in an old house in Nicosia, one story cueing another – and a quote-unquote ‘simple man’, shuffling through the names of a lifetime’s encounters.

Click here to change your cookie preferences