THEO PANAYIDES meets a man, born in Ceylon, who grew up all around the world with books and continues to live for knowledge, questioning everything even though he considers himself completely replaceable

We open at CVAR, the Centre of Visual Arts and Research in Nicosia, and an evening lecture called Approaching Art & History in Cyprus by Johann Pillai. Johann, shaven-headed, with alert expression and mellifluous English accent, is a smooth talker. I later find out that he had a mishap, crossing from the occupied north at the Ledra Palace checkpoint by mistake – he had to cross back in a hurry, running to the Ledra Street checkpoint then on to CVAR, and arrived drenched in sweat – but you’d never know. His theme is myths and fictions, the constructs we use in approaching art and history.

“The meaning of an artwork, or text, or historical event is not inherent in it,” he says from the podium, “but produced by the observer or reader in the act of seeing, framing, and interpreting it”. He prefers not to take the extra step of applying that explicitly to Greek and Turkish Cypriot versions of history – but does point out that group identity is also a narrative, a “collective fiction”. And of course, he adds, so the narrative doesn’t get reshaped, “there are warning signs posted everywhere and carved in stone, saying: ‘I will not forget’.”

With Anber Onar (wife) in Malaysia, 2015

A week or so later we meet at Mod, on the Turkish side just past the checkpoint, a day after his 59th birthday. He orders in Turkish, a language he speaks fluently though not quite with the ease of the native speaker. He’s been here 30 years, since 1992, with his wife Anber Onar, the two of them running an ‘arts and culture initiative’ called Sidestreets for about seven years (2007-14) in between sojourns in academia. He was here for the days of hope in the early 00s, from the opening of the checkpoints to the 2004 referendum, then for what you might call the days of cope, with bicommunal events and artists crossing back and forth – then by 2010-11 “it started fizzling out, and everybody went back into their corners. And of course the governments did nothing to help”.

The failure of the Annan Plan was the pivotal moment, of course. “I think, in the north, there was total disbelief when the majority said ‘No’ in the south. Because people here really thought this would be it. The ‘No’ vote was basically saying ‘OK, Turkish troops will be here forever’, so they couldn’t understand why this had happened – and the conclusion seemed to be ‘People in the south don’t want to live with us’. And that was a shock.” It all seems a long time ago now, the mood having curdled to “a kind of resignation… I think everyone would love it if there was some kind of solution – but I don’t know if the movement for peace has just turned into a ritual now… Because attitudes seem to be hardening on both sides”.

So much for politics. Johann is no stranger to this kind of fluid existence, that sense of reality shifting as you cross the Green Line (a simulated reality, like he said in his talk, etched out of constructs and fictions). The full name on his passport is actually ‘Niranjan Anthony Johan Pillai’ – because civil strife had already broken out in his native Ceylon in the 60s (before it became Sri Lanka) so his parents gave him a Sinhalese name in addition to his English and Dutch ones, “and they said ‘Depending on which way the conflict goes, use this name or that name’. They were very practical, my parents!”. That said, politics is only a tiny part of our conversation – and even the politics of Sri Lanka played little part in his life, since he left in 1967, at the age of four, and hasn’t been back since the 70s. Instead he grew up all over the world and remained, as he puts it, “external” to his various communities, cultivating a healthy (or perhaps unhealthy) suspicion of politics, ideologies, belief systems, and everything else that claims to give meaning to life.

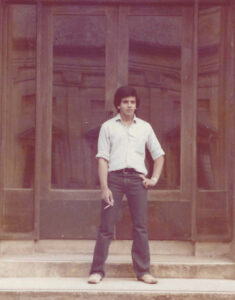

End of school in England, 1981

Johann’s parents were scientists, biologists in fact. His mum was a so-called ‘burgher’, descended from the Europeans who colonised Ceylon; his dad was Tamil, and a world authority on the microscopic marine worms called polychaetes. In 1967 he started working for the UN Development Programme, specialising in aquaculture – and from then on the family moved around, always to developing countries, first to New Guinea in Indonesia, then Tunisia, then Nepal, Tanzania, Nigeria. By that time, Johann and his sister had been sent to boarding school in England – in his case Prior Park College near Bath, run by the Irish Christian Brothers which, he admits, was “not pleasant”. In fact, “by the time I was 12 or 13, it became very clear to me that religion was a waste of time. So I was reading Nietzsche, things like that. I was [always] very interested in literature… From the time I was about six, we didn’t get toys, we got books”.

It was that kind of family: serious-minded, big on education, rather introverted, fearless when it came to scientific fieldwork. New Guinea, in particular, was an adventure, taking a double-engine Cessna (his parents wouldn’t fly in the same one together during the five years they were there, since the planes crashed so frequently) to a tiny settlement surrounded by a Stone Age culture where the men wore penis gourds and smeared themselves with pig fat in the cold season. Johann went to a missionary school, run by Mormons. There was no power, no running water, and stories of cannibals up in the hills. “My father rigged up a sort of contraption on the roof to collect rainwater, so we had a tank.” The local food was largely unpalatable, “so every week a plane would fly in from Australia to bring eggs and cheese, Kraft cheese in cans. We grew up on skimmed milk and canned food, and Fanta and Sprite”.

Food didn’t matter, in any case; even when his mother cooked, it was mostly ham-and-cheese sandwiches and what she called ‘Greek stew’. What mattered was science, going to the beach and learning the life cycle of every weed and crustacean; what mattered was literature, the kids getting “pillow cases full of books” for Christmas. Johann devoured detective stories, Agatha Christie and Perry Mason. Even now, though his projects tend to be literary – he’s currently working on an Edgar Allan Poe story called The Sphinx and an 18th-century German philosophical text, charmingly titled On Incomprehensibility – his strengths are largely scientific, and forensic. “I don’t write fiction myself. My creativity is in the analysis.”

All these elements – the rather cerebral scientific family; the citizen-of-the-world upbringing; the fact that he went to college in America in the early 80s, at the height of post-modernism – may have played a part in his restless, consciously untethered, intellectually curious, outside-looking-in sensibility. “I don’t have answers to things. I have the questions.” Then again, maybe he was always that type.

His sister, after all, having gone through a similar childhood, stayed in England and runs her own medical practice – but Johann started out doing Genetics and Microbiology at the University of Miami (where he met Anber, back in 1982 during their first semester), transferred to Yale and a BA in Literature, and has since taught all kinds of courses: World Literature, Modernism and Postmodernism, Political History of Cyprus, Semiotics for archaeology and art history students, even Jazz Appreciation in the music department. For the past year (after two stints in Turkey and a decade-plus at Eastern Mediterranean University) he’s been teaching Art History and Critical Thinking at a dance school – “the most amazing place”, the Pera School of Dance near Kyrenia. It’s unclear if dance students really appreciate a critical-thinking course – but they come from all over the world (the school has a great reputation), which delights his own internationalism.

Some might accuse Johann Pillai of being part of a post-modern globalist elite with no solid principles of their own – and he’d probably agree, except that he’d laugh and consider it a compliment. He has little time for God and country; “There are two great horrors, I think, in the world,” he tells me, “and those are nationalism and religion.” He lives for knowledge, and information. He gets news on everything (he’s on hundreds of Facebook groups, though he never posts anything personal) and forms his views accordingly. “If there’s one thing that I think I can pass on to students – apart from general unhappiness,” he quips, laughing heartily – “it’s to question everything… Question everything, and then decide where you want to stand.”

So, if someone were to ask what he believes in, the answer might be intellectual rigour, or something like that?

“No. I don’t believe in anything.”

Well, everyone believes in something.

“No. I don’t have beliefs. Because ‘belief’ to me already implies that you subscribe to something as a truth.” There are things he’s committed to (like women’s rights), and things he feels are generally fine, like democracy – though democracy only works with an educated public; “If you have a bunch of sheep who follow what their leaders tell them, then you don’t have a working democracy” – but nothing’s set in stone, and he’s always ready to tear down a truism if new information arises. “A scientist’s job,” he notes, “is to disprove.”

He’s a rationalist, a materialist. He doesn’t trust in history, or meaning, or memory. (They’re all convenient fictions we create without knowing.) He doesn’t believe in fate, or the concept of a soul, or life after death. Everything is chaos, and chance, and randomness – but our minds aren’t very good at grasping chaos, “and so people have to invent stories that connect things together”. He doesn’t even seem to believe in humanity, at least as some kind of higher good. “I think the problem is that everyone likes to think they’re special,” he notes mildly. “I don’t think like that. I’ve always thought I’m completely replaceable… I’m not interested in anybody remembering me as a person.”

It sounds a little shocking – though something should perhaps be made clear at this point, namely that talking to Johann is by no means disagreeable. He’s not grumpy, or disparaging; he doesn’t rage, or sneer, or put things down. He’s actually irreverent, eternally amused. Talking to him feels a bit like talking to a hippy or a travelling musician, asking dumb stuff like ‘But don’t you have a home? Don’t you earn a salary?’ while he chuckles and shakes his head. Beliefs and ideologies are indeed the slightly more exalted cousins of bourgeois fetishes like homes and salaries.

“I think there has to be a sense of irony in everything in life,” he muses – and seems to find succour in sharing weird stories (on the subject of life after death, for instance, did I know that you can now have the ashes of your cremated loved one inserted into a sex toy, the better to enjoy posthumous pleasure?) and enumerating random bits of trivia. His boarding school was once the private home of Ralph Allen, who invented the postal system. Radio Ceylon (which he’d listen to as a child) purloined its radio equipment from the wreck of a WWI German submarine. Johann went to study in Miami because his parents had a friend in that city, a 90-year-old orchid grower named Mr Ling. After almost two hours of chatting, he mentions that he’s written a book on mosaics – a subject that hadn’t previously come up, though the book (The Lost Mosaic Wall) is actually the convoluted tale of a lost artwork that Johann tracked down; his very own detective story, like the ones he read as a child.

But what makes him happy? “What makes anyone else happy?… Good conversation, good food, good exhibitions…” Not fatherhood, admittedly; he and Anber – who’ve now been together for 40 years; she was his first serious relationship – agreed from Day One that neither one wanted children. That said, there was something like parenting in the disadvantaged kids they helped during the Sidestreets years – the so-called Young Lights programme, teaching the children of labourers brought in from Turkey during the late-00s building boom (the old town of Lefkosa was something of a ghetto in those days). Most of the kids ended up with university scholarships – a tangible good that’s surely meaningful, even to an ornery post-modernist like himself.

“People have asked me ‘Where do you feel that you belong?’,” muses Johann Pillai. It’s a tough one. Not only is there no fixed idea in his life, he shies against the whole idea of a fixed idea in his life. Still, he says, “if the answer is ‘Where do you feel at home?’, then there is one place that I always feel at home – and that is the university. Because I can walk into a university anywhere in the world, and I know,” he points by way of illustration: “There’s a department where they speak my language. There’s a library. That’s the cafeteria… So my identity is not a national identity. It’s an academic identity”. A constant anchor, in a world of myths and fictions.

Click here to change your cookie preferences