After suffering a very dramatic mid life crisis, one stand-up comedienne turned her near-death experience into a show. THEO PANAYIDES meets a fast-talking live wire on her way to becoming a celebrity activist

“Are you ready, Nicosiaaaaa?” I don’t know – are we? The crowd goes wild, in any case – 500 people, maybe more, packed into the School for the Blind amphitheatre on a Tuesday night – as Katerina Vrana, the third-funniest person in the world, is wheeled in, to the pugilistic strains of ‘Eye of the Tiger’. Literally wheeled in, that is: in a wheelchair, by a middle-aged nurse called Fotini. For the past five years, since falling critically ill in April 2017, she’s been largely unable to walk without help, almost lost her vision – she actually did go blind for a while – and speaks in a slow, slurred fashion, like a drunk person trying to convince those around her that she’s stone-cold sober. To quote the Greek title of her show: ‘I Almost Died’.

She was 40 when it happened; she’s now 45. “It was a very dramatic mid-life crisis,” she quips dryly, in English (she’s completely bilingual), sitting in a coffee shop with a decaf cappuccino the day after the show. The ‘Funniest Person in the World’ contest, a kind of comedy Olympics organised by the Laugh Factory (she came third, representing Greece), was in December 2016. The winner was Malaysian, and invited a few of the other contestants to perform in his home country; there was even going to be a documentary, ‘What’s Fun in Malaysia’ – but then she almost died while on the tour, says Katerina, so the documentary got shelved “because it wasn’t so fun in Malaysia”.

It all happened so fast. She started feeling ill on a Tuesday – an intestinal perforation, “so a hole opened up in my bowels, which is very sexy”; by Friday she was hospitalised, by Friday night she’d almost died. The intestinal perforation led to sepsis, septicemia, then to septic shock “which is very serious, eight out of 10 people die.” Her issues now are mostly due to blood clots, at the cerebellum (the area in the brain governing balance and co-ordination) and behind the optic nerve. “There was no blood going to my eyes, because of the blood clot.” She went blind, but the doctors prescribed massive doses of cortisone and anticoagulants and “I’m now much better. I can see. Not very well.” At one point she asks Fotini – sitting at the next table – for a cigarette, and they go through a well-practiced dance as the nurse holds up the lighter and Katerina squints and bobs her head, trying to see the flame so she can touch it to the cigarette.

“My main issues are balance – it’s difficult to walk without aid – and very fine motor skills. I can’t drive, can’t put on my makeup, I can’t type. And my eyes. My eyesight is slightly fucked. My speech is okay, because I can still be understood.” The muscles and nerves in her legs are perfectly fine, it’s purely a matter of co-ordination. “My body’s just not sure what’s upright. I can stand – but I can’t stay standing for long, because my body thinks ‘Oooh, this way is up’ then ‘No it isn’t, you idiot, that’s down!’.” She laughs, in fact she laughs all the time – which raises an interesting question. People are forever being told that the way out of personal crisis is to try and hold on to your sense of humour; is it better or worse when crisis strikes a comedian, whose sense of humour is such an essential part of their being?

On the one hand, it’s worse – or at least more poignant. Katerina’s stage personality – which is also, she insists, her real personality – was a fast-talking live-wire, built on exuberance and happy energy; her jokes weren’t very edgy (there was stuff about the Greeks always yelling, and the English forming orderly queues) but the point was the person behind them. You can see her performing at the Comedy Store in London, circa 2009, whooping at the audience and chattering away at a speed of knots. “We don’t have a lot of time, so I’m going to talk about myself,” she informs them breezily. “And, if there’s time, we’ll move on to you.” In Greek, her most famous routine is (or was) the one where she plays a waiter in a taverna, running through the meze menu in about 30 seconds at ridiculous speed then asking “What will you have?”. She mentions that routine during the show in Nicosia – the audience applaud in recognition – then takes a stab at doing it at her current slowed-down pace, just to show how impossible it is, and she’s obviously being a good sport but still… it’s a bit sad, isn’t it?

Katerina rolls her eyes, as if to say ‘Can you believe it?’ – but she is still laughing and it is indeed pretty amazing, so much so that you start to wonder if she might be faking it. Her exuberance is almost too perfect, sitting there with her cigarette and coffee – bright pink dress, big frizzy hair, giant earrings – chatting away even with her slurred speech and disoriented body. “Freshly disabled” says her bio on Twitter (@vranarama), making a joke of it. Is it a performance? – but in fact that question misses the point. It might well be ‘a performance’ – but only because Katerina is a natural performer; this is who she is. Did she always want to be a stand-up comedian? “No. I always wanted to be onstage.”

Cracking jokes wasn’t necessarily her bag, though her family in Athens had – and have – a great sense of humour (“They’re not really entertainers,” she explains. “They’re just naturally silly people”). She actually studied Drama, at Royal Holloway just outside London, then spent two decades struggling, like most performers. She did some acting, small dramatic roles in obscure productions. She did the usual admin and back-office day jobs, to make ends meet. At one point she turned to comedy improv, honing her craft by going to open-mic nights – you can always find one in London – and riffing for five minutes at a time. She’s never been the type of comic who writes down the jokes; she learned by doing (“I’m good at ad-libbing”), and seeing what an audience found funny. Then came the crisis in Greece and she suddenly found herself getting invited to panels and talk shows, as a bona fide Greek who nonetheless spoke English without an accent.

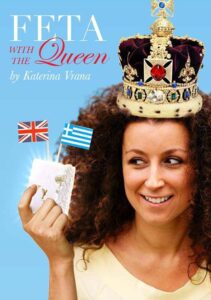

She toiled all through her 30s, gradually becoming better known. In 2009, she made the finals of a big competition in the UK. In 2013, CNN – reporting from the Edinburgh Fringe – named her as one of ‘13 funny female comedians to watch’. Then came About Sex (and its predecessor Feta With the Queen, another big hit in Greece), then came the ‘Funniest Person in the World’ accolade, the kind of exposure that can lead to a sitcom role or a Netflix special. And then, just as her career was finally taking off after years of struggle… well, that’s where we came in. Speaking of jokes, it looks like the universe is also pretty good at playing jokes, no?

“Clearly I must’ve raped babies in my previous life,” she agrees, deadpan – but in fact that kind of bad-karma fatalism isn’t her style. “I never think like that, I have to say. For me, it was just cause and effect. My body was giving out signs that things weren’t well from a year before. For a year I wasn’t feeling well, I had stomach pains, I had massive issues – I ignored all of it. I kept saying, ‘After the next show, after the next tour…’ So at one point my body went, ‘Bitch, I can’t wait for you! I’ve tried. You’re taking forever’. So I don’t blame the universe, I blame mostly myself – which is why I’m not angry. I was a malakas”.

Everyone knows ‘malakas’, of course, the ubiquitous Greek ‘wanker’ – but in fact ‘malaka’ (actually Malacca) was also the Malaysian city where Katerina almost died. “For a Greek comedian,” she guffaws, “that’s a godsend!” This is how she turned her experience into comedy, for those who may be wondering – not by trying to make light of obviously awful things, but by riffing on the things she actually does find funny. Even at the time, she always knew this was going to be good material. “The number of times I was lying in bed thinking ‘This could make a good joke. This too. And this’…The [only] issue was, how soon can I get onstage? Can I get onstage in a bed with, like, an IV in my arm?” She laughs at the image. “Or do I have to wait?”

It’s therapy too, that goes without saying. Everyone deals with life-altering crises in different ways – and a natural performer will (naturally) do it by performing. It’s important to be supported “in the way that you need to be supported,” says Katerina: “I need a lot of humour, a lot of fun. I hate pity!”. Live shows give her energy (she tried performing over Zoom, but it wasn’t the same); she’s a person who craves warmth, and human contact. Did this whole experience make her more spiritual, at all? “Basically, what happened confirmed my deepest beliefs,” she offers. “Because I woke up from nearly dying, feeling such a deep sense of peace and love – it felt like I was flooded with love for everyone. To the point where my brother was like, ‘I don’t know what drug they have you on, but this is ridiculous!’.” Katerina smiles: “I’ve always believed that the strongest thing is love”.

Love doesn’t die, it appears – it just changes form, like energy. Katerina was in a relationship when all this happened, but it didn’t survive the upheaval. “He was amazing,” she makes clear. “He’s still amazing, he’s a lovely person. It’s just, through this process we became friends and lost the…” She shrugs, letting the sentence trail off – but her love is still there, it just got swept into performance and social activism. One might think her days are boring, given her limited mobility – but in fact she’s constantly in the media doing interviews and panels, “because right now there’s a wave in Greece with regards to disability rights, and visibility of disabled people”.

The universe, it seems, wasn’t just being sadistic. The timing was terrible, yet oddly fortunate. Katerina Vrana is a comic using her disability for comedy (it’s part of the way she lives with it) – yet she’s also, now, a disabled person using her comedy to become a celebrity activist on behalf of the disabled. She’s always been “driven by my dreams,” she says; those years of struggle and silly part-time jobs were so frustrating. I’m tempted to joke that getting sick was a great career move, but worry about sounding crass; I needn’t have worried. “One of my favourite jokes is that, if I had known I’d get this famous, I would’ve tried to die sooner!” adds Katerina, and laughs again.

And the future? What’s the prognosis? “There is no prognosis.” She’s getting better, slowly, erratically. She’s full of plans, including a return to the UK (Covid willing). Stand-up comedy is never really about the gags, it’s about the person revealed behind them – and her story reveals an uncommonly strong, forthright person. “It requires a lot of confidence,” she tells me, “and a kind of skewed way of looking at things. Because you have to be able to find the funny anywhere.” When life gives you lemons, as they say, make lemonade. Or just make jokes about lemons, that works too.

Click here to change your cookie preferences