THEO PANAYIDES hears about the mixed blessings of growing old from a straight-speaking Limassol-based woman looking back on a life ranging from corporate wife in America to ground breaking reiki teacher in Cyprus

Growing old, as Bette Davis famously opined, is not for sissies – and, whatever else June Long might be, she gives no indication of ever having been a sissy. “I’m what they call an ‘adult child’,” she tells me. “An adult child is someone that was an adult from the time they were born.” That was in 1927, “the year of the first talking picture” (the film was The Jazz Singer, with Al Jolson), meaning she turned 95 this past May. We talk in her small flat in Limassol, with Yiangos – a former taxi driver who’s been her companion since she arrived in Cyprus in 1989 – hovering in the background and an ancient cat named Buffy shuffling about disconsolately. “I should have her put to sleep,” muses June. “But I can’t bear it.”

Growing old is a mixed blessing. Actually no, it’s not a blessing at all – but it does allow one to drop the mask of politeness and sentimentality, and tell the honest truth about oneself and others. A 95-year-old is like a child in that respect; they’re not bound by the usual social strictures – especially when they’ve been through as much, and looked death as often in the face, as June has. Her first husband “was a mother’s boy,” she says bluntly – not to be unkind, that’s just the way it was. “He wanted looking after… He was an irresponsible man.” Her opinion of the heirs to the Lanitis fortune is probably unprintable – the old Lanitis estate was just behind her apartment, Mrs Lanitis (who was Scottish) was a friend, but now it’s a building site for Trilogy, one of the infamous towers going up all over Limassol – nor shall we name the local hospital where the male nurses (though not the women) are “arrogant little bastards… The last one I had was responsible for this becoming infected,” she adds, pointing to a bandage on her leg.

She has several bandages, from frequent falls (“I keep getting vertigo”), but the nurse in question ripped off the bandage clumsily, and was very harsh with her besides. “Some men are not suited to be nurses,” she observes mildly, “because they have not – shall we say – assimilated, or absorbed, their one-third female [part].” Men are one-third female, women vice versa. Is she also one-third male?

“That’s why I survived,” she replies. “I have more than one-third male… At least I think so.”

What defines the maleness?

“My ability to take charge – which is what the male part of a man does, takes charge and sorts things out. That’s what I’ve been doing most of my life.”

And before that? What did she do? Oh, loads of things. She was in retail, a manager at Royal Doulton when she first came to Cyprus on holiday (a couple of years before actually moving here). She sold real estate in Hawaii, or tried to, and would certainly have stayed – she loved the energy – had she been more successful. She became a corporate wife for a while, with her second husband. She taught creative writing, and wrote some fiction of her own. She lived in the US for about 40 years. She worked in a post office, became a partner in a construction company in Delaware making prefabs and home improvements, even sold Avon door-to-door when things got tough. “So I have no patience with people who say ‘It’s beneath me’. Nothing is beneath you if you need a job.”

It could all have been different, of course. That’s the lesson of life, how it eddies and flows into something we never intended. “When I was a child,” she recalls, “my only ambition was to sing opera, or to be a writer.” It wasn’t just an idle dream, she was actually training to become a soprano at the Royal Academy of Music – but a blister on her hand (!) turned out to be life-changing. The blister became infected, and she went into hospital for blood poisoning. She was 17; this was 1944, hospitals chaotic and plagued with shortages because of the war. The whole experience “ran me down,” she explains, “and the rest followed” – ‘the rest’ being tuberculosis, spelling an end to her dreams of a singing career and leading to a whole year in a sanatorium. “They told my mother I wouldn’t live to be 20,” says June, with obvious satisfaction at just how wrong ‘they’ turned out to be.

What does having tuberculosis feel like?

“What does it feel like? First, you lose all your strength. You can’t breathe properly. You’re exhausted all the time, you can’t do anything. And you cough, and you cough, and you cough. And sometimes you haemorrhage.” The treatment in Britain was still Victorian (she got TB again in the US, after her divorce, but the treatment was more humane there), and involved deliberately collapsing the lungs – the idea was to give them a rest, and allow them to heal – by injecting oxygen with a needle into the chest cavity and increasing the pressure till the lung collapsed. The oxygen had to be refilled, which she did every week for five and a half years; on VE Day she had a haemorrhage, when an inexperienced doctor tried to pump in air and “went too deep with the needle”.

TB derailed her life in other ways too. Doctors said she shouldn’t have kids, and arranged for an abortion without even asking her when she accidentally got pregnant later. (“I didn’t really want to have a child by my first husband,” she shrugs, “so I wasn’t unhappy about that.”) June never did have children, nor does she have any nephews or nieces; she was an only child, and indeed “an unwanted child” – hence why she calls herself an ‘adult child’, “never looked after, always having to look after someone else”. I ask about her parents, and she gives a little laugh: “That is a drama!”. Her mum – who was also tubercular – “wasn’t well, and she was always getting herself into trouble”. (What kind of trouble? “Men. She was very attractive.”) Her dad, on the other hand, was “quite a man”, maker of the first-ever coloured photogravure picture – it’s in Watford Museum – and world-class amateur golfer.

June herself also used to be a keen golfer – and was also tomboyish as a child, climbing trees and shooting bows and arrows. (The neighbourhood kids were all boys, she explains, so she had to do everything they did.) At the risk of over-simplifying, it looks like she might’ve grown up gravitating more towards ‘masculine’ traits, maybe associating femininity with her troublesome mother – and looking for that take-charge, independent quality in men, too. Even when it came to politicians, she admired Churchill and FDR for being decisive: “De Gaulle was useless, he was just a ditherer!”. Europe was “an unholy mess” after the war, she recalls sadly. “When I look back at it, I married an American to get out of Europe.”

That was Husband No. 1, a GI she met at a party – but “the wrong man,” she admits (a mother’s boy, as already mentioned), though they stayed together for nine years. Her second husband, Richard, was altogether different. He was 15 years older, had been married before – a disastrous marriage, to a “fanatical Baptist” with peculiar ideas about sex – and worked, for most of their marriage, as a manager at Mack Trucks, a big corporation. He was the man of her life, then? “He was,” she agrees. “He was not only the man of my life; he was a friend. He was a protector. He was a teacher… He taught me how to shoot, he taught me how to fish. How to find my way in the woods.”

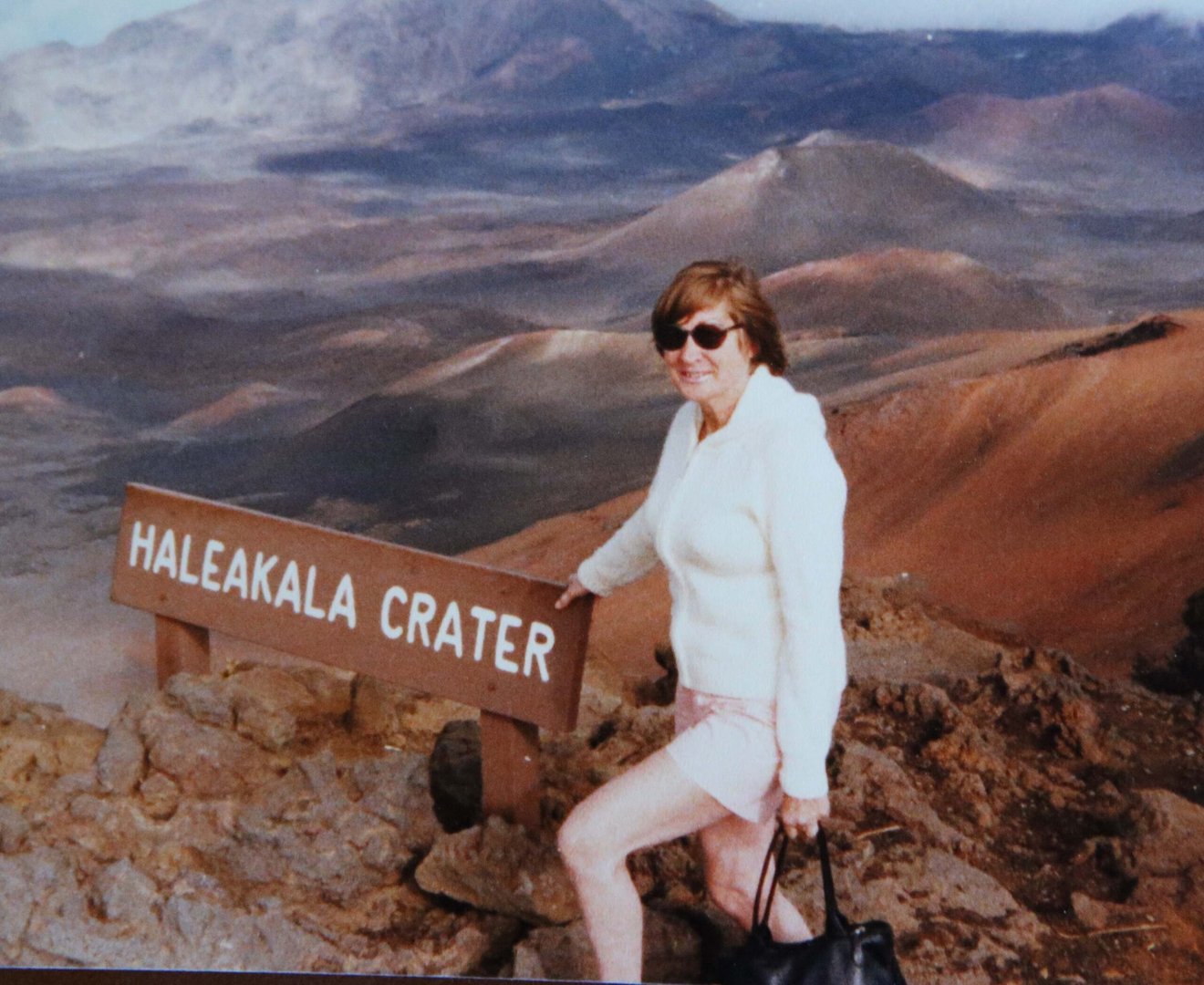

June in Hawaii

Those were the happiest years of her life, says June (though the early years in Cyprus were enjoyable too, teaching reiki and exhibiting at Mind, Body & Spirit) – living on a farm in Pennsylvania with Richard, sailing to Canada on their 36-foot boat, camping on the shores of Lake Superior in virgin forest. They never divorced, only separated; he died a few years after she came to Cyprus. Why did they not stay together, though? She shrugs: “The 15 years between us was a lot, at that time,” she offers. She was still young, looking for adventure; in the end, they wanted different things. “But I always loved him. I always will.”

Sounds like she could’ve gone back, I suggest.

“He had made himself another life. It was a good life. Why would I go back and destroy that?”

Maybe he missed her too?

“Maybe,” she sighs. “Maybe he missed me. I think maybe he did, because he didn’t divorce me.” She could never abide the corporate life, though: “Being an executive wife – which I was – you’re expected to behave a certain way”.

How?

“Well – it’s hard to explain. But you’re expected to kowtow. I could never kowtow.” This was in the 60s, of course; it must’ve been something like Mad Men, the husband in the office and the little woman back at the house. She was younger than the other wives, more of a wild child. She recalls one cocktail party when she got very drunk and ended up sitting in the lap of the president of the company; it wasn’t so bad (she and the man’s wife were friends, and played golf together), and everyone thought it was funny – but Richard was mortified. June recalls him “pushing me into the car”, feeling his unhappiness. “And then we had to have a – oh my God, ‘a lunch’. It went around. Everybody had to have a lunch, for the women – and everybody tried to outdo each other.” She hosted a few lunches, cooking fancy meals, but then “I got sick of it. So, the last time, I made them beef stew!” she recalls, and laughs uproariously. “That did it! I just couldn’t stand it anymore, it was so false.”

Should she, perhaps, have stuck it out? That’s the problem, though: you never know – even if you live to be 95 – which specific permutation of life might’ve been the happiest, especially when life is so fragile. June’s had other near-death experiences, not just TB: cervical cancer at 42, attacked by a bear while on a camping trip, getting rear-ended (hence her spinal problems) not once but twice, the second time by a “professional accident driver” who rammed into random cars for the insurance. One might say she’s lucky just to be here – yet ‘here’ isn’t really very nice at the moment.

“This is not me,” she sighs, gesturing vaguely at the flat and Limassol in general. Wrong place? “Wrong place, at the wrong time.”

She has other regrets; she doesn’t sugar-coat it. (You stop trying to sugar-coat things, when you grow old.) She’d have loved to stay in Hawaii, but it wasn’t meant to be. The dream of being a writer, like the dream of being a singer, never really panned out. “It’s not a good place to end up,” she admits philosophically. “Maybe it’s my karma – I don’t know. Maybe I did more damage than I know, and this is paying me back. What goes around comes around… Maybe I’ve hurt people.” Did she ever hurt people? It doesn’t sound like she did. She thinks about it, lost in a reverie for a moment: “Looking back, I think I hurt my husband,” she replies quietly.

In the end, it is what it is. You live your life, and end up at 95 (if you’re lucky) wherever the universe sees fit to deposit you. At one point, June mentions her great friend Francesca Pinoni who used to run Mind, Body & Spirit, and praises Francesca’s organisational skills. So what would she say are her own strengths? “Survival!” she replies instantly – and laughs, looking back on a turbulent, not always happy life. “I’ll go when I’m ready. You know what I mean?” I think I do.

Click here to change your cookie preferences