In an internationally known and respected referee, THEO PANAYIDES meets an entertaining and organised man still capable of fancy footwork who is shocked by the increasing violence in his native South Africa

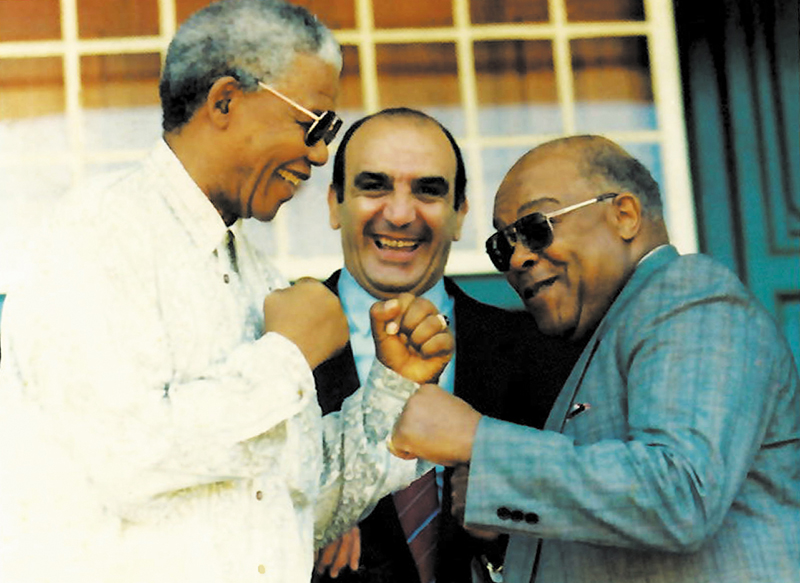

Stanley ‘Stan’ Christodoulou deeply admired Nelson Mandela, the charismatic leader of his native South Africa; more intriguingly, the feeling was mutual. Stan, one of the great boxing referees of the past 50 years – inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2004 – was awarded the State President’s Award by Mandela for his services to grassroots boxing in South Africa, despite having already received the award (which is meant as a once-in-a-lifetime honour) from Mandela’s predecessor FW De Klerk. The two men also met fairly regularly, at luncheons and state events, and would often swap boxing stories, Mandela being a big fan and former amateur boxer himself; Stan, even now, is delighted to recall that “his two favourite boxers were mine as well: Sugar Ray Robinson – pound for pound the best middleweight of all time – and Joe Louis”.

Stan with Nelson Mandela and IBF president Bobby Lee

Robinson and Louis are familiar names, of course – but I can’t say I’ve ever watched footage of their fights, nor would I really consider myself a boxing fan. I’m not entirely sure how our conversation’s going to go, sitting at a café in Nicosia with Stan and his wife Mary; fortunately, talking to the now 76-year-old boxing legend – the first man to referee world-title fights in all 17 weight categories, though also, for many years, the executive director of the South African Boxing Board of Control, which was how he kept running into Mandela – is an entertainment in itself. He talks spectacularly fast, seems to have total recall of the thousands of fights he’s judged or refereed, and punctuates his stories with oft-told jokes and distinctive turns of phrase. His style is direct, assertive: “The ref was right,” he declares at one point, apropos of some long-ago bout, “and I’ll tell you why”.

He’s a man’s man, big and bluff and hearty. Mary is quieter and more circumspect, acting as a kind of gentle brake on his more boisterous tendencies. He shows me a photo of himself as a handsome 17-year-old, a time when – remarkably – he was already overseeing fights in South African townships. D’you know, he goes on, I was talking to the wife recently “and she said to me, ‘When we married, you looked like a Greek god’. ‘And now, darling?’ ‘Now you look like a god-damn Greek!’.” Stan roars with laughter; Mary smiles but shakes her head shyly, to show it’s not true.

They’ve been married for 51 years, and raised four children. They’re only in Cyprus for a few days, for his brother’s memorial service (it’s been a tough time: Stan lost two of his three older siblings in the space of a month), though they’re hoping to move here sometime next year, driven away by the usual concerns over crime in South Africa. How they met is a story in itself, suggesting something of Stan’s personality. He was driving his mother and sister to his other sister’s house in Pretoria, he recalls, and stopped for a packet of cigarettes. As he came out of the store he ran into Mary coming in, and – he indicates thunderstruck love at first sight – “I got a shock, you know?… I said ‘I love you!’. Just like that, spontaneous.”

“My friend Nitsa had a shop, and I said I’d help with baking the cakes for her little one’s birthday party,” says Mary, taking up the thread. “And as I’m walking into the shop he’s coming out, and he looked at me and said, ‘I love you! I love you, do you want to go steady with me?’. I thought, ‘He’s mad, I’ve never seen him in my life before’.” Nitsa, it turned out, wasn’t in the shop, so Mary left – “and as I came out he was sitting in the car, waiting!”. Stan started driving alongside her; “I was getting nervous. He said ‘Can I give you a lift?’, I said ‘No thank you, I don’t accept lifts from strangers’.” These days we’d probably call him a stalker and throw him in jail for harassment – though admittedly his mum and sister were also in the car, and Stan’s mother soon began asking after Mary’s family (she’s also Greek-South African, though from Crete and Limnos rather than Cyprus). In the end, Stan hurried back to Johannesburg, spruced himself up – then returned to Pretoria to meet Mary’s parents, that same night.

It’s a good story – though probably not a very representative one. Stan may have been impulsive in matters of the heart, but his style has always been organised, rigorous: “I’m a systems man,” he tells me. Then again his own parents had a similarly whirlwind courtship, albeit not exactly a ‘romance’ since it was an arranged marriage and his dad was 30 years older. Dad came to South Africa in the late 1920s and opened a shop in Brixton, Johannesburg – “a very tough area”, like its South London counterpart, so that his son “grew up fighting the local guys… I had a lot of street fights”. It was all in self-defence, he pleads, though it got quite intense (he had a few serious scraps, even with men twice his age, and was even starting to graduate from fists to bottles as he grew older) – and meanwhile he was also obsessed with boxing, collecting books and magazines some of which he still has today. (His filing system is impressive; he’s ‘a systems man’.) Stan became an amateur boxer, and quite a handy one (12 fights, 12 wins), but a broken knuckle sustained in a street fight got in the way – so instead he worked in a bank and kept his head down, till one day in 1963 when Willie Toweel walked in.

As a ref he’s been involved in some classic bouts, from his world-title debut (his “baptism of fire”, as it says in the book), Arnold Taylor vs. Romeo Anaya for the bantamweight title in 1973 – a four-knockdown epic named by The Ring magazine as the greatest bantamweight fight in its history – to Marvelous Marvin Hagler vs. Roberto ‘Hands of Stone’ Duran for the middleweight title in 1983. His style was unobtrusive; like all the best people in every field, he made it look easy. “They’d call me ‘the invisible referee’… At the end of the day I’m just there, I keep out of the way, I enforce the rules and I want justice”. He’d train like a boxer himself – a ref needs his own fancy footwork, just to be able to keep up for 15 (now 12) rounds – and would also pray before each fight (he’s very devout), asking the Lord “to fill me with His holy spirit”. Once or twice the footwork deserted him and he got in the way of a punch, including a slam to the chest in a heavyweight fight that felt like he was having a heart attack.

There were other issues too. Once, in Korea, as Stan walked to the corner to mark his score card between rounds (this was in the days when the ref was also one of the judges), a disgruntled trainer attacked him with a pair of scissors. Another time, in Madrid in the mid-70s, the welcoming committee included what he calls in the book “a very attractive Spanish senorita” who made it clear she’d do anything – anything! – for the local fighter to win. “I’ve never been unfaithful to my wife, I love her immensely. Look at her picture,” demurred Stan, showing the girl Mary’s photo. “I said, ‘You can rest assured, I’ll be as fair as possible’.”

Looking back, that senorita was definitely barking up the wrong tree – because any hint of corruption seems to be anathema to his upbringing, his religious beliefs, and indeed his personality. Stan recalls his Polis-born mum – a very dynamic woman, by all accounts – telling him she’d “rather put you six feet under than [have you] disgrace our name”, and the same approach ruled his tenure at the Board of Control. “I’m a very stringent person with systems, and decency – and I made sure that there must be integrity. Like as a referee, you never compromise your integrity.”

The same was true, apparently, with being a dad. “He taught his children honesty, integrity… He was a strict father, that’s why they were all successful,” volunteers Mary. “Because he was very strict, they wouldn’t dare bring a bad report home.” That said, he could be gentle too. “He was away a lot, but when he came home he always made up for it with the children. Playing with them, they’d climb on his back…”

“Follow my eyes,” says the man himself with a mischievous twinkle, looking at Mary as if to say ‘She’s the reason why’. “Follow my eyes… If I didn’t do that, you know what I’d get for supper? Hot tongue and cold shoulder! And no dessert!” he adds with a broad wink, and an enormous laugh.

“That’s one of his jokes,” she smiles, shaking her head with practised embarrassment. “I think I married him for his sense of humour more than anything.”

It’s quite sweet, the mutual appreciation between this long-married couple – and they’ve been through a lot, but life in South Africa sounds especially bad right now. “I’ve seen some brutal fights,” notes Stan, yet he’s still shocked by this level of violence: “They used to break in, but before they robbed you, now they shoot you and kill you as well. It’s out of control.” There’s a paradox here, insofar as he’s shocked by violence yet spent his whole professional life around violence (he still judges bouts, and refereed till a couple of years ago) – yet he doesn’t really see the paradox, because of course boxing isn’t ‘really’ violence.

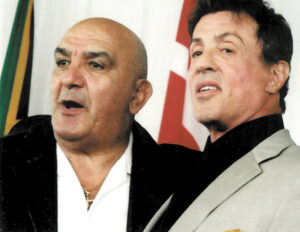

Stan with Rocky Actor Sylvester Stallone

“Professional boxing is unlike most other sports,” he admits in his book. “In a modern world that’s becoming increasingly sanitised and over-regulated, boxing remains what it has always been, a brutal test of fire for the two fighters”. Stan never officiated in a match where someone got seriously hurt – “No, thank God, praise the Lord, never!” – but he’s seen a boxer die in the ring, and of course everyone saw Muhammad Ali in his later, punch-drunk years; “That’s the ugly side of boxing”. Yet he’s also adamant that – as long as systems are in place, of course – the sport is about as safe as it can be; fighters are closely monitored, and made to take an MRI if damage is suspected (“They don’t do that in rugby, or other sports”). It’s the referee’s dilemma, nonetheless: stop a fight too soon and you go against the very art of boxing (not to mention getting crucified by the big-money types who may have bet thousands on the outcome), stop too late and you could end up with a fighter with brain damage. “I’d rather stop it one punch too soon than one punch too late, that’s always been my motto. But you’ve got to time it right.”

He’s still going, as already mentioned, still full of energy, nor would the move to Cyprus mean retirement per se (if anything, it’d make it easier to officiate in Europe). Stan’s hobbies have always been sporty, golf and cycling in the past, bowls nowadays (“Old man’s marbles,” he quips). I suspect he’s a natural athlete, even if he didn’t actually compete in the ring – he’s got an athlete’s discipline and forthright, truth-telling personality, especially when you add his strict values and iron-clad respect for the rules.

“I sum things up as they are,” he concludes. “Maybe I’m not popular, but I do it correctly and justly.” It’s too bad he didn’t stay in the banking world, with his love of systems; “I’d have been a wealthy man,” he agrees. “But I’m happy. When the bug bites you…” The bug bit a street-fighting kid in a rough-and-tumble part of town; 60 years later the kid’s done it all, carving his own little footnote in boxing history. The life and times, indeed.

Click here to change your cookie preferences