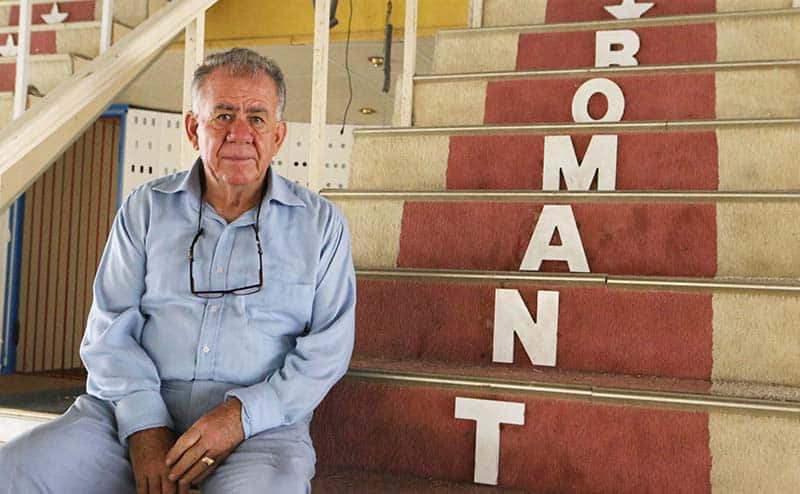

THEO PANAYIDES meets the owner of what was once referred to as the Moulin Rouge of Cyprus, a place visited by all presidents

We’re in the British bases, a few miles before Ormidia, the lone jogger in the late-morning heat being presumably a soldier from the nearby camp at Dhekelia. The road bends and suddenly there it is, an enormous sign on the old road to Ayia Napa: ‘Romantzo Restaurant’. There’s a decorative fishing boat below the sign – and the little cove is indeed a fishing shelter, Romantzo overlooking a sleepy, idyllic bay with around 20 skiffs pulled up to the shore, fishing nets bundled up in bags on their sterns. I climb a flight of narrow stairs to the restaurant, and pause at the sound of a dog yapping. A small black mutt appears closely followed by its owner, 68-year-old Constantinos ‘Dinos’ Englezou. His name is Blackie, says Dinos fondly, gazing down at the little mongrel – and he’s “my best friend”.

The photo on the bike was taken in 1973, six months before his dad was killed. “I was orphaned at the age of 19,” says Dinos (using ‘orphaned’ to mean losing his father, as befits the patriarchal society in which he grew up). It was a car crash, a head-on collision, an ironic detail given that the boy – like his dad – was mad about cars, planning to go to England and study mechanical engineering. Dinos wasn’t just some village lad from Ormidia. He’d just graduated from the American Academy with excellent A-Levels, one of 37 students in their UP (University Preparatory) class; one of his old classmates now owns three clinics in Paphos, he tells me with undisguised bitterness, another is a noted economist. His own life, however, changed radically – because, in addition to being a model pupil and aspiring engineer, he was also the oldest of 10 kids, his younger siblings ranging in age from two to 16.

Dinos had enlisted for national service in July 1973; his dad was killed on August 4 – and of course he was immediately discharged, since he was now the head of a family. With hindsight, the sole silver lining was that he was spared from having to fight in 1974 – but that was scant consolation for having to upend all his plans and somehow raise a family as a teenage boy. “I was their father, let’s say. And my mother was my wife!” he recalls with a dry laugh. “I had to find a way to make money to raise nine children. It wasn’t easy… I can’t tell you how many times I sat down and wept.”

He started out as a fish seller (in addition to running Romantzo, which never closed), teaming up with an old man “because I was too embarrassed, at 19, to be going around yelling ‘Fish!’”. They collected produce from the local fishermen and went up the coast in an old Hillman, all the way to Famagusta then back through the Mesaoria villages if there was fish left over. It brought in some money – but he soon realised that only a thriving business could provide enough of a regular income to fulfil his new responsibilities. He became a vegetable farmer, renting land from the Brits to grow potatoes and cucumbers, and made good money for a while; he brought in red soil from Avgorou at his own expense, selling a speedboat for £500 and getting a loan from his father-in-law (he was married by then) for another £500. “I was very active.” And hard-working too, by the sound of it? “Very! 18 hours a day, seven days a week – that was my life. That’s why I can’t sit still now,” he adds, gesturing vaguely at the empty space around him. “And this place that you see here, it didn’t appear just like that. You have to work to create it… This one, and the one before, and the one before that.”

Alas, the good times didn’t last very long. The place closed entirely in 2020, due to Covid, but in fact it had been moribund for years. A TV show used it for location shooting, a group of English ladies held their afternoon tea parties here, a smattering of customers might arrive for Sunday lunch – but in fact, says Dinos ruefully, “I haven’t had money in my pocket since 1998”. Ask me how much I have on me right now, he challenges, looking at me glumly from beneath his crown of grey hair.

Okay. How much?

“€10… And it’s not like I have any more in the bank or anything. And what arrived just now,” he adds, pointing to his phone which had beeped a few minutes earlier, “that’s my pension. Which I’ve been waiting for with bated breath, so I can get through the month on €600.”

The whole situation is hard enough – but what makes it even harder, I suspect, is the kind of person Dinos Englezou is. He’s always been a high achiever, “a perfectionist”. The red soil he brought for his orchard is one example; another, less obvious example has to do with the foreign staff he used to employ, mostly Bulgarians and Romanians. Many bosses picked up a bit of the language so they could converse in broken fashion, but he never did: “Because if I say something, I need to know that I’m saying it right”. He’s the kind of man who doesn’t forget a slight, or a missed opportunity – and can’t quite forget the path his life might’ve taken, had his dreams not been scuppered.

Dinos was sociable (you have to be, in his line of work) – but in fact he’s a reserved, rather introverted person: “I was low-profile, let’s say”. He’s clean-living, doesn’t drink or smoke, and was always very big on doing things right – which was also why he got on well with the Bases authorities. “One reason why this building’s here is because I was a man of good character, so they let me build it”; had he been a drunkard or drug pusher they’d surely have closed him down, “the British are very careful”. Even the Larnaca underworld, who might’ve tried to claim a piece of the action, respected him as “a good man who was raising nine orphans”. He never had any trouble, even as a big music venue in the heady 90s.

The Brits and the gangsters were helpful – but others obstructed him, and tried to destroy him. Twice he’s come up against institutional corruption: once in 1989, when ministry officials – presumably paid off by rivals – tried to close him down, claiming he was building illegally, and before that in the early 80s when a jealous neighbour got the Department of Land and Surveys in Nicosia to adjudge that a big chunk of Dinos’ land belonged to the neighbour. (“It was in the days of Diko, and he was Diko.”) The second time he was saved by the Bases commander, who took his side (just as well, since he’d mortgaged his home and staked everything on the new building). The first time was even more alarming – since, after all, what recourse do you have when a public body officially finds against you? “I didn’t know what to do… I couldn’t sleep at night.” He and the neighbour were in court for five years; he sank to the other man’s level – he couldn’t afford to lose Romantzo; he had nine mouths to feed – and went to Nicosia with bags of fish as ‘gifts’, trying to find someone to help him; it might’ve been farcical, if it weren’t so serious. Dinos tells these stories with an air of implacable sorrow, as if talking of some natural disaster – but it’s clear he’s forgotten nothing, even all these years later. “You know what I went through? You know how upset I was?” He shows me a patch of discoloured skin on his arm – a remnant of his various troubles, when his liver stopped producing melanin due to all the stress.

There’s a bit of good news, among all the bad: in 2019, after years of trying, Dinos and his offspring were granted a 25-year lease by the Bases – and Romantzo could surely work again if the wherewithal could be found to re-open it, assuming he still has the energy. It’s hard to know precisely what to make of his story. He’s morose, and undoubtedly bitter; he seems to have been so unlucky. In the end, perhaps his most noble traits were also liabilities – the sense of duty which bound him to his task, however onerous, the perfectionism that some may have seen as aloofness, the principled outlook which meant that “I never asked for help from anyone”. (Every MP and politician in Cyprus knew Romantzo; but he never sought favours.) Dinos sighs, trying to sum it all up: “Most people aren’t – well, they aren’t like me, let’s put it that way”.

There’s a postscript to this rather sad tale. It’s late October but intensely warm, a glorious day; I decide to drive the 20 minutes down the coast to Ayia Napa and have a swim. Later, at a sandwich place, I fall into conversation with the middle-aged owner and mention where I’ve just been – and this random stranger instantly nods in recognition when I mention Romantzo, its legend still stirring the blood after all these years. “It’s a shame,” he muses thoughtfully, shaking his head. “Beautiful place like that, right on the beach. They could’ve made millions…” I think back to the grey-haired man in the half-empty space, the photos, the trophies, the stairs going up to the dressing rooms – and the little black dog, his best friend.

Click here to change your cookie preferences