In March this year, a new firm appeared in Turkey’s corporate registry. Azu International Ltd Sti described itself as a wholesale trader of IT products, and a week later began shipping US computer parts to Russia.

Business was brisk, Russian customs records show. The United States and the EU had recently restricted sales of sensitive technology to Russia because of its Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, and many Western tech companies had suspended all dealings with Moscow.

Co-founded by Gokturk Agvaz, a Turkish businessman, Azu International stepped in to help fill the supply gap. Over the next seven months, the company exported at least $20 million worth of components to Russia, including chips made by US manufacturers, according to Russian customs records.

Azu International’s rapidly growing business didn’t come from a standing start, Reuters reporting shows: Agvaz manages a wholesaler of IT products in Germany called Smart Impex GmbH. Before the invasion, Russian custom records show that the German company shipped American and other products to a Moscow customer that recently has imported goods from Azu International.

Reached at his office near Cologne in October, Agvaz told Reuters that Smart Impex stopped exporting to Russia to comply with EU trade restrictions but sells to Turkey, a non-EU country that doesn’t enforce most of the West’s sanctions against Moscow. “We cannot export to Russia, we cannot sell to Russia, and that’s why we just sell to Turkey,” he said. Asked about Azu International’s sales to Russia, he replied, “This is a business secret of ours.”

Contacted again shortly before publication, Agvaz said Smart Impex “observes all export restrictions and manufacturer bans” and “has not circumvented Western sanctions against Russia.” He said he couldn’t answer questions about Azu International. Turkish corporate records show he sold his 50 per cent interest in the Istanbul company on Nov. 30 to his co-founder, Huma Gulum Ulucan. She couldn’t be reached for comment.

Azu International is an example of how supply channels to Russia have remained open despite Western export restrictions and manufacturer bans. At least $2.6 billion of computer and other electronic components flowed into Russia in the seven months to Oct. 31, Russian customs records show. At least $777 million of these products were made by Western firms whose chips have been found in Russian weapons systems: America’s Intel Corp, Advanced Micro Devices Inc (AMD), Texas Instruments Inc and Analog Devices Inc., and Germany’s Infineon AG.

Entrance door of a building homing a business center where the microelectronics trading company Azu International, registered by Gokturk Agvaz, has its offices in Istanbul, Turkey, November 15, 2022. REUTERS/Dilara Senkaya

A joint investigation by Reuters and the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a London-based defense think tank, details for the first time the global supply chain that continues to feed Russia with Western computer components and other electronics. The investigation into this trade identified a galaxy of obscure importers and exporters, like Azu International, and found that shipments of semiconductors and other technology continue to arrive in Russia from Hong Kong, Turkey and other trading hubs.

One Russian importer, OOO Fortap, based in St. Petersburg, was set up by a Russian businessman in April and has since imported at least $138 million worth of electronics, including US computer parts, according to Russian customs records. They show that one of Fortap’s biggest suppliers is a Turkish company, Bion Group Ltd Sti, a former textile trader that recently expanded into wholesale electronics. Bion’s general manager declined to comment.

Another Russian importer, OOO Titan-Micro, registered an address that’s a house in a forest on the northern edge of Moscow. It, too, has imported Western computer components since the invasion, according to the customs records.

Some of the suppliers – including firms in Hong Kong and Turkey – have ties to Russian nationals, according to a review of company filings.

The customs records – which Reuters purchased from three commercial providers – don’t identify the precise type of semiconductors and other electronic products, nor do they show what happens to the components once they arrive in Russia. Reuters reported in August that Western companies’ mass-produced chips, in many cases not subject to export restrictions, have shown up inside missiles and weapons systems the Russian military has deployed in Ukraine.

Reuters provided to Intel, AMD, Texas Instruments, Analog Devices and Infineon data from Russian customs records that detail shipments of their products that have arrived in Russia in recent months. Reuters excluded data between Feb. 25 and March 31 to account for shipments that might have been in transit before the invasion or before the manufacturers’ announced suspensions.

A spokesperson for Intel said the company is taking the findings “very seriously and we are looking into the matter.” The spokesperson said Intel adheres to all sanctions and export controls against Russia and “has a clear policy that its distributors and customers must comply with all export requirements and international laws as well.”

Similarly, a spokesperson for AMD said the firm “strictly complies” with all export regulations and has suspended sales and support for its products in Russia. “That includes requiring all AMD customers and authorized distributors” to stop selling AMD products into Russia.

Infineon, too, said that after the invasion, it “instructed all distribution partners globally to prevent deliveries and to implement robust measures that will prevent any diversion of Infineon products or services contrary to the sanctions.”

A Texas Instruments chip dated 1988 is seen on a circuit board found inside a Russian 9M727 missile that was collected on the battlefield by Ukraine’s military and presented to Reuters by a senior Ukrainian security official, in Kyiv, Ukraine, July 19, 2022. To match Special Report UKRAINE-CRISIS/RUSSIA-MISSILES-CHIPS REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko

Texas Instruments said it has not shipped to Russia since the end of February. Analog Devices didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A spokesperson for the US Department of Commerce said, “Since the start of the invasion, Russia’s access to semiconductors from all sources has been slashed by nearly 70 percent thanks to the actions of the unprecedented 38 nation coalition that has come together to respond to (Russian President Vladimir) Putin’s aggression. It is no surprise that Russia is working hard to circumvent controls.”

But the Reuters review of Russian customs data found that since the invasion, the declared value of semiconductor imports by Russia has, in fact, risen sharply. The spokesperson said the Commerce Department had analyzed different data and therefore couldn’t comment on Reuters findings.

Putin’s office and Russia’s Ministry of Industry and Trade didn’t respond to requests seeking comment for this article.

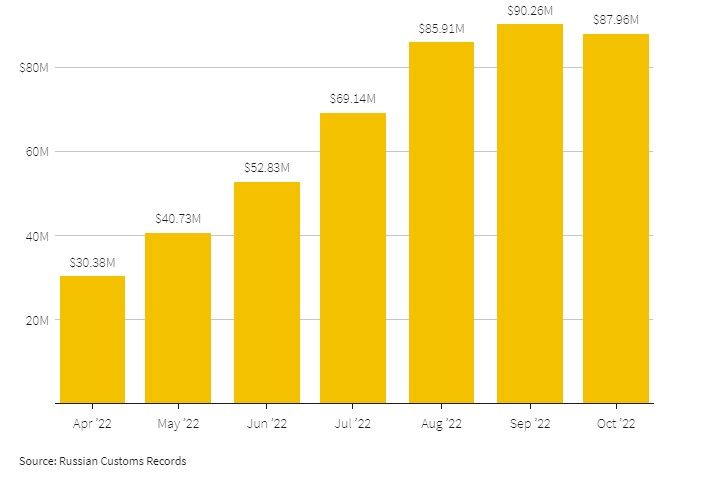

Exports of Intel products to Russia

On March 3, 2022, US semiconductor maker Intel Corp said it had suspended all shipments to customers in Russia. Reuters found at least $457 million worth of Intel products arrived in Russia between April 1 and Oct. 31, 2022.

Stacks of boxes

Among the firms shipping Western technology to Russia is a Hong Kong- registered company called Pixel Devices Ltd. A Reuters journalist who visited Pixel Devices’ office in a Hong Kong business tower found a small room with cardboard boxes stacked to the ceiling, and no employees. There was little sign that the company has shipped at least $210 million in electronics to Russia since April 1, including at least $50 million in Intel and AMD products through Oct. 31, according to Russian customs records.

Company records show that Pixel Devices was incorporated in 2017 by a Hong Kong firm called Bigfish Investments Ltd, controlled by Kirill Nosov, a Hong Kong resident with a Russian passport. Nosov told Reuters in an email that he helped set up the firm but doesn’t work for it and isn’t in a position to comment about its activities.

Pixel Devices’ current owner is a Singapore company, Asia Global Neolink Pte Ltd, which in turn is owned by a Seychelles company called White Wings Ltd, according to Hong Kong and Singapore company records. Pixel Devices’ only director at present is Pere Roura Cano, a Spaniard, who is also listed as a director of Asia Global Neolink and runs an aviation club in Catalonia. Reached by telephone in Spain, Roura Cano confirmed that Pixel Devices has been shipping semiconductors and other products to Russia.

“I’m beginning with these people and I’m not sure what goods are moving,” he said. “I cannot inform you more; it’s our private activity.”

Pixel Devices’ website, www.pixel-devices.com, was originally registered in 2017 with a web-services firm in St. Petersburg, according to internet intelligence firm DomainTools. The website states that Pixel Devices’ “Components & Subassemblies” division serves businesses in diversified sectors including military and aerospace. In response to questions from Reuters, Pixel Devices said it doesn’t sell products to the military sector and prohibits its customers from reselling to defense companies. It said some of the information on the website is “quite outdated.”

Pixel Devices said it has been supplying IT equipment to Russia for several years and “it is possible” that it shipped Intel and AMD products this year “as part of long-term contracts.” It said it acquires its products from manufacturers or their resellers and doesn’t supply components “that violate any binding policies imposed on the company by its partners, vendors, or distributors.” Intel and AMD told Reuters that Pixel Devices isn’t an authorized distributor of their products.

Pixel Devices said it couldn’t confirm the accuracy of the values found by Reuters of the company’s exports of electronics to Russia; it didn’t provide its own figures. It also noted that export restrictions aren’t universal and there isn’t a complete ban on the export of IT equipment to Russia. The company said it doesn’t sell to entities controlled by sanctioned individuals.

Pixel Devices also said it’s not surprising that no one was in Pixel Devices’ office recently because most employees work remotely or in warehouse operations.

Russian customs records show that Pixel Devices’ main client in Russia is a company in St. Petersburg called OOO KompLiga. Its website, states that the firm can supply a wide range of IT products and parts. According to the customs records, since April 1, KompLiga has imported at least $181 million worth of electronics, almost exclusively from Pixel Devices.

KompLiga’s general manager, Aleksandr Kotelnikov, told Reuters he was reluctant to provide details on how his company manages to continue procuring Western electronic components. “I’d rather not disclose details about my company’s work so as not to tip off rivals and give them a helping hand in their hard work,” Kotelnikov wrote in an email.

“Iron curtain”

Not every Russian company is reluctant to discuss how to deal with export restrictions. A Moscow-based logistics firm, OOO Novelco, has been advising Russian businesses on how to continue importing foreign goods.

In September, Novelco organized a seminar in Moscow for its clients on “how to find alternative ways to deliver goods” to Russia. In a 45-minute presentation entitled “Foreign trade tactics and strategies to compensate for sanctions,” Novelco’s chief executive, Grigory Grigoriev, urged companies to stockpile products and develop diversified pools of suppliers from more than one country.

One Novelco executive offered a tip for clients tempted to use the Chinese territory of Macau as a shipping point to Russia: “We do not recommend sending cargo through this airport, despite the attractive rates, as there are enormous waiting times, cancellations.”

To resolve shipping problems, he and other Novelco executives have recommended on the company’s YouTube channel using lessons learned during the pandemic, such as transporting goods through third countries, rather than directly from a supplier.

In interviews with Russian media and in a series of posts on LinkedIn, Grigoriev described recent trade restrictions on Russia as tantamount to erecting an “iron curtain” around his country.

Grigoriev said in one LinkedIn post that Novelco had set up an affiliate in Istanbul and has been shipping goods to Russia from Turkey, which doesn’t enforce all US and EU Russian trade restrictions. Once merchandise arrives in Turkey, “shipments are processed for re-export and cargo can follow to Russia by air, sea, road and rail transport,” Grigoriev said in the post.

In March, Grigoriev registered in Istanbul a company called Smart Trading Ltd Sti, Turkish corporate records show. Since then, the company has shipped at least $660,000 worth of products made by US semiconductor makers, according to Russian customs records.

Some other Russian firms believe it is unwise to discuss publicly how to handle trade restrictions.

In an August blog post, a senior executive at F+ tech, a Russian IT equipment manufacturer that relies on many imported components, said the business of procuring foreign parts requires discretion.

“We ourselves increase the risks of sanctions by publicly reporting on who will carry what and from where,” Evgeny Krivosheev, F+ tech’s head of production and development, wrote in a blog post, which was published by Russian business daily Vedomosti and on the company’s website. “Such publicity attracts unnecessary attention.”

A spokesperson for Krivosheev’s company said the executive wasn’t speaking about any particular firm.

EU shipments

Many recent shipments of Western computer parts to Russia have arrived from China and other countries that haven’t joined the United States and the EU in restricting exports to Russia.

But there are some exceptions, Reuters found. Customs records show shipments of Analog Devices and other US components directly from the EU.

Elmec Trade Oü, an electronic-components wholesaler based in the Estonian capital Tallinn, shipped at least $17 million worth of goods to Russia between April 1 and Oct. 31, according to Russian customs records. These included chips made by Analog Devices and other US manufacturers, the records show.

Elmec Trade’s general manager, Aleksandr Fomenko, told Reuters that his company buys its products through official channels, follows all legal requirements and complies with all sanctions and export restrictions.

Asked how his company could continue to export Analog Devices and other Western chips months after the manufacturers announced they had suspended sales to Russia, he said that “the majority” were orders placed last year. The shipments were delayed because of pandemic-related transit disruptions, he said. Analog Devices didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A spokesperson for the European Commission didn’t respond to questions about Elmec Trade. In general, the spokesperson said, “The EU takes circumvention very seriously, as it is a practice that can undermine the effectiveness of EU sanctions.” The spokesperson noted that the 27-member bloc has been encouraging other countries to align with EU measures adopted against Russia.

Eleventh floor

The US government has placed export restrictions on scores of companies to try to stop the flow of sensitive high-tech components to Russia. But the probe by Reuters and RUSI found that there appears to be an active roster of substitute players ready to replace such entities.

Take the case of AO GK Radiant, a Moscow-based distributor of computer chips and other electronic parts that celebrated its thirtieth anniversary in June. It states on its website that its objective is to provide Russian clients with “the best solutions from global manufacturers.”

Indeed, Russian customs records show for years the company had imported millions of dollars worth of Western-designed chips.

But in July 2021, the US Department of Commerce added the company to its trade restrictions list, alleging that it was “involved in the procurement of US-origin electronic components likely in furtherance of Russian military programs.”

Russian customs records show that GK Radiant’s imports have since plummeted. The company’s founder, Andrei Kuznetsov, declined to comment.

The company’s head office remains on the eleventh floor of a building at 65 Profsoyuznaya Street in Moscow. There also appears to be another importer of Western computer components operating on the same floor. It’s called Titan-Micro.

The house, where, according to Russian corporate records, electronics distributor OOO Titan Micro is registered, is seen in Moscow, Russia November 10, 2022. REUTERS/Stringer

Russian customs records show that Titan-Micro began importing Analog Devices and other electronic components in November 2021, nine months after it was established. Titan-Micro has since imported at least $12.7 million in parts, including $9.9 million worth since April 2022. It has used some of the same suppliers as GK Radiant, including Sinno Electronics Co Ltd, a Chinese company that was placed under export restrictions by the US Department of Commerce in June for allegedly providing support to Russia’s defense sector. Sinno Electronics didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The address for Titan-Micro listed in Russian corporate records leads to a wooden house, deep inside a birch forest in northern Moscow, with no apparent sign of business activity.

The company’s general manager, Nadejda Shevchenko, hung up when Reuters reached her by phone. But a Titan-Micro employee, who declined to give his name, later said employees weren’t working at the wooden house, but on the 11th floor of the business center at 65 Profsoyuznaya Street.

That’s where GK Radiant also operates.

Click here to change your cookie preferences