Driven by the pursuit of knowledge, one former civil servant who has spent most of his adult life in the shadow of Makarios Avenue tells THEO PANAYIDES about his life as a geologist, father and translator of Shakespeare

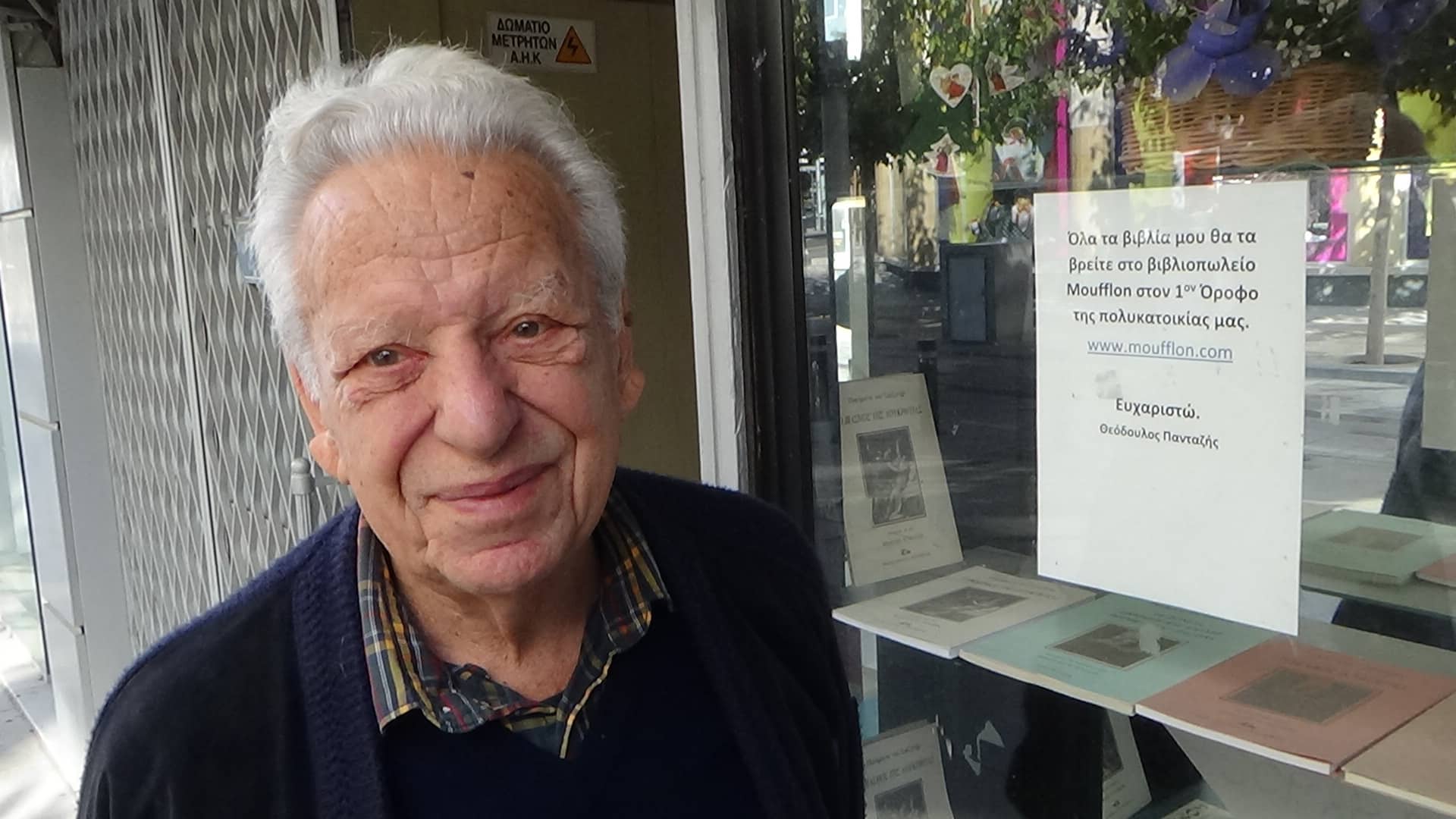

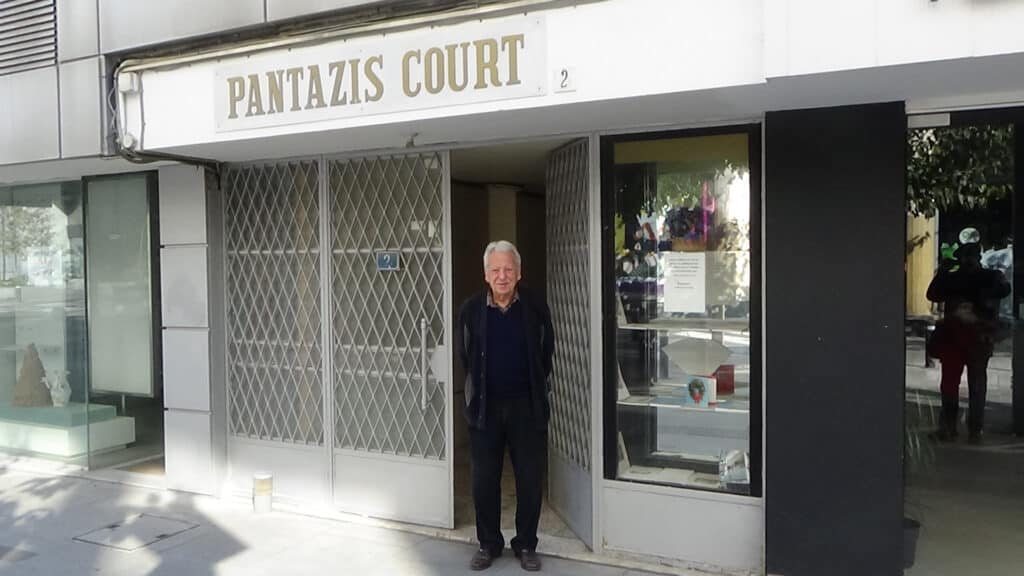

At the entrance to Pantazis Court, on the fabled Makariou (Makarios Avenue) in Nicosia, a few slim volumes sit in a glass case, accompanied by a typewritten note in Greek: “You can find all of my books at Moufflon bookshop, on the 1st floor of our building”.

The note is signed ‘Theodoulos Pantazis’ – and the books, as confirmed by a visit to Moufflon, are a mixed bag, various geological surveys from his years as a geologist at the Ministry of Agriculture but also, for instance, translations of Shakespeare, from Hamlet and Othello to a selection of sonnets. It’s all quite intriguing.

Pantazis Court is intriguing too, halfway down what used to be the main shopping street of Nicosia and directly opposite the 360 building, the redoubtable, recently-built skyscraper that promises (or threatens) a new Makariou. Stand outside the Court, gazing across the main road, and the 360 towers imposingly; take a few steps in the other direction, down Mnasiadou, and you reach the old, two-storey stone house where Theodoulos lives with his wife Marina, a bubble of tranquillity amid the fevered dreams of developers. The garden is full of citrus trees, and flowers he’s planted himself. Next to it, in an alcove below the main house, is a study and a small bathroom, with a shower for cooling off after a morning’s gardening. He can still shower without any help, he notes with satisfaction, at 87.

The threads of his life run together, not always coalescing into any particular fabric – but any 87-year-old will invariably have done a lot and lived through a lot, especially when he’s been successful in society and owned a chunk of the city’s most valuable real estate. Mementos punctuate our conversation, reminders of this or that thread. Upstairs in the house is a painting from Guyana, purchased during one of his many trips representing Cyprus at scientific conventions. Among his papers is a letter (dated July 2, 1974) from Archbishop Makarios himself, signed in beautiful red cursive, congratulating Theodoulos on his thesis – on the geology and geochemistry of Troodos – which led to a professorship at the University of Athens (something of an honorary post, since he remained a civil servant too). In the study downstairs is perhaps his proudest keepsake, though all the lettering – including his name – has faded now, seven decades later: the top mathematics prize for 1953 at the Pancyprian Gymnasium, a great honour for any 18-year-old.

It was even more of an honour – not to mention useful – for a boy from a poor family. Theodoulos grew up in Linou, the son of a welder at the Cyprus Mining Corporation; the fine stone house on Makariou (like Pantazis Court, and the property in general) came much later, from his wife’s family – but he passed the exam for the Pancyprian and everyone said he had a “mathematical mind”, so two of his friends clubbed together to sponsor a few private lessons with a Mr St George, an old English mathematician. Theodoulos still recalls – “I’ll never forget it” – the greeting this old eccentric yelled out to his new pupil, a kind of imaginary dialogue in fluent Cypriot: “Ekso shylle Englezo! Pou fefki, re pelle” – roughly translating as ‘Begone, English dog! He’s not going anywhere, mate’. It was a joke, but a topical one: ‘Britain Out’ sentiment was rife in the early 50s. Theodoulos, however, wasn’t involved, either with the first Eoka or, two decades later, with Eoka B. “I wasn’t political – and I also felt, as a personal opinion, that we actually had it very good with the English. Maybe it’s because my dad was at CMC.”

The methodical nature of colonial bureaucracy may have appealed to him. In the service, he recalls, he was always known for “writing a lot of minutes”, i.e. little notes and directions in the case file. His style is meticulous, even pedantic – though “I’m not meticulous in life, in fact I’m quite messy,” he adds lightly, gesturing at the rather disordered room around us.

His mind is mathematical, and not especially poetic. Yes, he’s translated Shakespeare (purely as a hobby), indeed his translations and related teaching aids became the standard in Greek and Cypriot high schools, at least while they were still teaching Shakespeare – but his versions of the plays are prose, not poetry: the speeches appear as run-on paragraphs, with no attempt at approximating Shakespeare’s rhythm. He did take on the job of translating the sonnets too, but that was never his favourite. “The sonnets are boring, to be honest. Very boring”; he much prefers narrative poems like Venus and Adonis, where “you’re saying to yourself ‘Let’s see what happens next’”. His trump card was never poetry, but accuracy: previous Greek translations of Shakespeare – even in the early 90s, when he did the work – weren’t derived from the originals, but from earlier translations in German and Italian. His own versions are works of scholarship, with footnotes pointing out mistakes in older versions; one predecessor, he recalls scathingly, had translated ‘sledded’ with a reference to travelling by carriage, presumably because of some ambiguity in some third language.

Like any scientist, he’s essentially driven by knowledge: the pursuit of knowledge, which also implies education. Theodoulos has enormous respect for education; we talk very briefly of his two sons (both middle-aged now, of course) – and I never do learn their names, but I find out straight away that one is “a Harvard boy” while the other is “London School of Economics and an MBA in America”. His own studies went far beyond his initial degree, in Natural Science and Geography at the University of Athens (that maths prize led to a scholarship). He was at Imperial College twice in the 60s and 70s, pursuing postgraduate courses in Geology and Geochemistry, not to mention the aforementioned thesis (the one for which Makarios offered congratulations) and the title of FIMM, a Fellow of the Institution of Mining and Metallurgy in London, bestowed in 1973.

“I like to write, I like to study, and I like to go in depth,” he explains. Since retirement – in addition to the Shakespeare translations, which actually came earlier – he’s penned about a dozen (unpublished) dissertations on various topics, from the Old Testament to the Greek War of Independence. Theodoulos Pantazis seems to be one of Nature’s scholars – a disposition that would fit very nicely into research or academia, less so in the Cyprus civil service, a subject on which he has mixed feelings.

Both his sons work in the private sector; “Stay away from government!” he recalls telling them, adding that “Theodoulos” – he likes to talk about himself in the third person – “rose up the ranks, but only up to a point”.

And what happened then?

“Then,” he notes lightly, “we reached the stage of being beheaded.” He smiles grimly: “In the end, the Makarios supporters considered Theodoulos Pantazis to be anti-Makarios”.

Any 87-year-old will have lived through a lot. Theodoulos has been through the various stages of Makarios Avenue – from buzzing thoroughfare to ghost town and hopefully back again – and he also lived through the stages of Cyprus as a nascent republic, the intrigues and rivalries, the influence of the archbishop, the corruption that outlived him and indeed became even more pervasive. He dates his own problems to 1973, when he was secretary of the association of primary-school parents (despite his scholarly nature he’s always been very sociable, he tells me, and was always a popular choice as a representative or committee member). The three bishops of Cyprus had rebelled against Makarios, trying to defrock him and oust him from the clergy – and a prominent woman called for the association to send a telegram of support to the archbishop. Theodoulos replied, quite sensibly, that it was nothing to do with them – and put the motion to the board, who agreed with his view.

“From that moment, I was branded as anti-Makarios. Though, since I wasn’t Eoka B, it was harder for them to present me in that way and bump me off – because you know, they were killing people in those days!” Things got worse a few years later when the department’s official geological drill was taken out secretly on a weekend, to do some drilling on Makarios’ land. Theodoulos found out, and made a fuss – in writing too, he says, shaking his head at his own imprudence – and was warned that his life was in danger. “I would put matches on my car,” he sighs. “If you place them just outside the door, you can tell if they’ve been moved [i.e. if the car has been opened],” he explains, noting my bewilderment.

He didn’t leave the civil service – and of course he wasn’t fired, but he was ‘beheaded’, as he says; his career stalled. He may have been too outspoken, though not because he was anti-Establishment – more because he was too scholarly, too methodical. He tells me of the Bentonite clay scam, a project calling for the government to buy tracts of land containing the clay in question – but in fact our local clay isn’t up to international standards, which Theodoulos knew from his studies in the UK, “and, being an idiot, I put my knowledge to good use”. He wrote an expert opinion debunking the scheme – but in fact the whole thing was corrupt from the start, the idea having been to scam the state out of millions (then announce that, alas, no good clay had been located), and the various high-ranking officials who’d stood to gain weren’t pleased by his intervention. Like the man said, ‘This is Cyprus’.

Is he bitter about all this? “No, I’m not bitter,” he replies, “because I brought a lot of these things on myself.” He was never very streetwise, shrugs Theodoulos – and talk of streets brings us to his own street, which I actually thought would feature more prominently in our conversation. (We probably end up talking more about Makarios himself than the avenue that bears his name.) Makariou wasn’t just for shopping when he arrived, newly married, in 1963. It was a meeting point, a street for parading down, to see and be seen – and of course for boys to walk alongside girls, and vice versa. The street was mostly houses, but already everyone had their eye on bigger things. He recalls a house down the road being declared a listed building, meaning it couldn’t be developed – and, soon after, a bulldozer arriving in the dead of night to tear it down, at the owner’s behest of course.

He took out a loan – £2,000 in 1970 – and built four shops; Pantazis Court was born. The town’s leading shoe shop was among his tenants; so was Timinis boutique. Nicolaou pharmacy was here for 51 years, an institution. The rent for the corner shop alone was over €3,500 a month – at least in the glory days. “In 2013 it went dead,” he recalls, though no-one seems entirely sure why. Obviously the haircut played a role, the never-ending roadworks, the rise of the malls. Theodoulos himself is unequivocal: “What happened after 2013 was that the unions told the shopkeepers: ‘Don’t pay [your rent]’… What destroyed the market in Makariou was this strategy of not paying rent”.

Well, maybe – but surely the issue was that the rents were too high in the first place? Couldn’t the problem have been solved if landlords like himself had been more flexible? Could the old Makariou have been saved? Or was it just a stage that had to happen, an unavoidable decline paving the way for the new Makariou of gleaming towers and expensive steak houses?

Theodoulos Pantazis won’t be drawn on this point, indeed I’m not even sure he cares all that much. He’s 87, after all. He’s done a lot and lived through a lot, raised a family and travelled to Guyana, survived – and occasionally thrived – in the civil service and also translated Shakespeare, the books you can find at Moufflon on the first floor of ‘our’ building. We say goodbye, then he showers me with gifts – a geological map of the seismic zones of Cyprus, prepared by Th. Pantazis PhD, DIC (Eng Geol), FIMM, Chartered Engineer; a bag of freshly-cut oranges from his garden – and I take my leave, walking out of the old stone house, past the entrance of Pantazis Court and onto the bustling main road, the latest iteration of Makariou.

Click here to change your cookie preferences