In a proud but troubled Cypriot poet and bookworm, THEO PANAYIDES finds someone for whom books themselves have stories, and not just the ones inside them

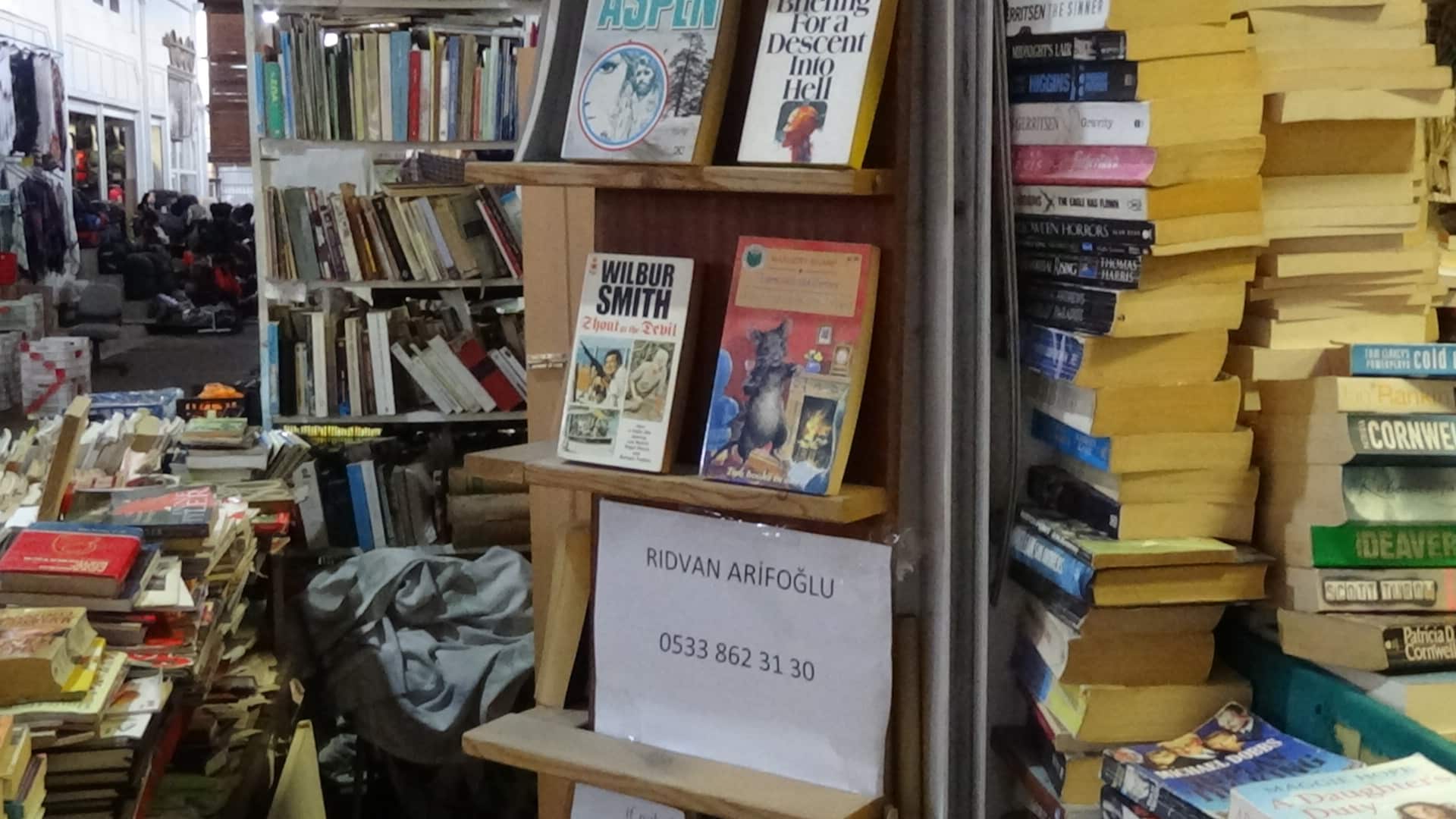

The book is at the top of the pile. I pick it up, browsing idly while waiting for Ridvan Arifoğlu to finish with a customer: Second Generation by Howard Fast, published (I check inside the cover) in 1978.

It opens on an improvised bookmark, an old stub of paper. On the back is a name and address: Pamela (the surname is hard to make out) from Pacifica, California. I turn the stub around and realise it’s actually a boarding pass for Saudia flight SV193, dated September 3, 1981. How did Pamela from Pacifica end up in Saudi Arabia? Did her husband work for an oil company? Did she buy Second Generation to read on that flight, 42 years ago? The fact that her boarding pass is still inside suggests that she didn’t look through it much – if at all – after she’d read it. Did she just hoard it mechanically, the way we often hoard books? Did it languish for months, or years, on a shelf in Riyadh? Did she then move back to Pacifica, and clear out the house – which is how the book eventually made its way to a second-hand stall in the Bandabuliya, in the occupied north of Nicosia?

He’s a wry 48-year-old, rather unsmiling but good-natured, with large expressive eyes in a pouchy face. He makes me coffee on a tiny stove amid the piles of books, then puts on a vinyl record (‘She’ by Charles Aznavour), part of a recent shipment he received from a music store that closed down. “I have to listen to all of them,” he says, of the records; “Most antiquarians don’t do this”. It’s unclear why he himself feels that he has to – but maybe it’s about establishing control over his domain, feeling that he knows every nook and cranny. A bookseller is often an introvert, ensconced in his own book-lined world.

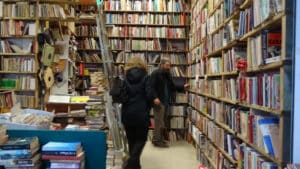

The Bandabuliya isn’t really his domain, a rowdy warren of small shops selling clothes, souvenirs and food products. There are greengrocers both in front and to the left of him; their customers often block his entrance, and the constant racket makes it hard to concentrate. The location is admittedly useful in attracting tourists, and foreigners in general (the customer being served while I was browsing through Second Generation was a young African – presumably a student – buying The Testimony of Steve Biko), but this isn’t where Ridvan feels most comfortable, and of course it’s too noisy to do an interview. Instead, two days later, we meet again and he leads the way to one of his ‘warehouses’, an unmarked shop on a quiet street near the courts in Lefkoşa.

He often comes here on Sundays – the one day when the bookstore is closed – he tells me, drawing a curtain to let in some light and pouring two generous slugs of whisky; there’s a room at the back, with a bed where he spends the night sometimes. This shop, too, is piled high with books – some of them his own books, not just those he’s written (three books of poetry, plus one of essays) but also those he’s owned over the years. He’s been in the business for about 14 years, the shop in Bandabuliya (opened in 2015) being his third location; before that he was near a school – “I thought teachers read,” he recalls, laughing to indicate how wrong he was – then near the courts, where “I understood that lawyers also don’t read too much”. Before that he was in Istanbul for some years, studying architecture, returned to Cyprus in 2003 and taught at university for one semester before going into bookselling. He disliked academic life as it’s practised here, he says, especially the way even professors are forced into promotional work, “they send them to Turkey to talk about their university”. It doesn’t really sound like such a deal-breaker – but perhaps it offends his sensibilities, the pursuit of knowledge (like the world of books itself) as a kind of pristine sanctum.

It’s a sad affair, the plight of the Turkish Cypriots, increasingly beleaguered (and outnumbered) even in their own small society. “Many people, especially young people, don’t think they are living in their own country anymore,” he says. “We have a –” he struggles, trying to find the words – “a soil, the north part of Cyprus. We know it, we spent our childhood here. Turks from Turkey, they don’t understand. They can’t feel this”.

Oddly enough, he often feels more Cypriot when he crosses over to the Greek side, “because of music… It’s the same music,” he adds, noting my puzzled look, “the language”. But we speak Greek, I point out, and you speak Turkish. “It doesn’t matter.” The rhythm, it seems, is similar, Turkish Cypriot dialect bearing the same relationship to the cadences of mainland Turkish as Greek Cypriot does to Greek. Language is important, it defines a culture; it was hard enough having to talk in an Istanbul accent during his time on the mainland – but it’s even more frustrating now, when he has to switch to ‘good’ Turkish when conversing with a settler who doesn’t speak the dialect. “You have to change it,” he sighs, “and you cannot talk relaxed”. It’s something Greek Cypriots can identify with – yet few will even be aware that their counterparts in the north have the same problem. “I think Greek Cypriots must support Turkish Cypriots more,” offers Ridvan, in his mild way.

Language is important, it creates a world. That’s the kind of poetry he loves, the kind that uses words for their high-flown, imaginative properties: “I like poets who create an atmosphere, especially modernists” – Ece Ayhan and Turgut Uyar in Turkish, people like Eliot and Cavafy (“Cavafy is very important for me”) in the rest of the world. His own poems seem to be along the same lines, though they’re only available in Turkish – but, for instance, Google translates one title (‘Deniz Varliğimi Yüzdürsün’) as ‘Let the Sea Flow My Existence’, which certainly sounds rather high-flown. It’s no surprise that his favourite author is James Joyce, especially Ulysses – a difficult book, for sure (it took several attempts before he finally mastered it), and one where you have to take the plunge and fully inhabit it. “It’s a world,” he explains. “If you decide to go into a world, it’s okay.”

There’s a kind of poetic through-line here: in the free-standing literary worlds he so admires, in the isolated world of Turkish Cypriots, and indeed in Ridvan’s own world which seems quite self-sufficient, bordered on all sides by books. Is he lonely? Does he have lots of friends? “Not many friends. Generally lonely,” he replies with a laugh. (I should really have said ‘alone’.) “Sometimes it’s hard – but it’s okay.” He’s at the shop six days a week, organising shelves and taking delivery of new books, sometimes noting ideas for new poems when it’s not too noisy, chatting with tourists and compiling an unofficial list of literary mentions of Cyprus (there’s a reference to Cyprus wine in Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, apparently: “It’s a bad wine there, ‘Cyprus wine’ means a bad kind of wine… Most probably it was Commandaria, they don’t like that!”), then unwinds on Sunday with his whisky and cigarettes; he has no hobbies to speak of. “Generally I read. I like reading. Music, sometimes movies. Not an adventurous life,” he admits, with another wry laugh.

Then again, isn’t every book an adventure? Not to mention the back-stories, if we’re talking second-hand books – the book’s secret history, Pamela from Pacifica and all the other Pamelas. I browse the shelves and find a dog-eared copy of Enid Blyton’s Five Have a Wonderful Time (about 20 per cent of Ridvan’s stock is in languages other than Turkish, mostly English and German), the flyleaf inscribed with ‘Julie, Xmas 1971’ and an address in what looks like Yorkshire; he bought it from a British couple in Kyrenia, he confirms. Sometimes he can sense – though of course you can’t ask about these things – that the person selling the books is divesting themselves of an ex-lover’s stash, left behind after the break-up; often, they belonged to parents who’ve died, and the person is reluctant to part with them – yet “they also want them to be read”. More than once, he’s imported a book from Turkey (often a signed copy) then had the Turkish Cypriot author in his shop as a customer, face-to-face with his own book – a rather sad occasion, since the reader for whom they signed it clearly didn’t value it much and sold it on to a dealer in Istanbul, after which it made its way back to Cyprus. Books travel.

What’s the most valuable tome on his shelves? Ridvan shrugs, as if to say the question isn’t very interesting. He has Ottoman-language books which are worth quite a lot, and various rare first editions – but what’s more important is the hoard itself, the rich diversity of his little world. Here’s a small pile of Arabic VHS tapes (VHS, mind you, not even DVDs). Here’s a book called Holiday in Seychelles, published in South Africa and written in 1972 by one Douglas Alexander – a kind of Lonely Planet before the fact, listing historical facts and sites of interest. The back cover touts Holiday in Mozambique, also by Mr Alexander; “Even for people not likely to visit Mozambique, this is an intensely interesting book,” claims a quote from the Natal Mercury – which seems unlikely, but I guess the bar for ‘intensely interesting’ was lower in those days.

In the midst of it all sits Ridvan Arifoğlu: poet, bookworm, proud-but-troubled Cypriot. He’s exactly as old as the invasion (he was one month old at the time), and has felt the slow, inexorable social decay of the 48 years since. Selling second-hand books is frustrating – most people just don’t read very much – and living as a Turkish Cypriot is also frustrating, but he loves his work and wouldn’t live anywhere else; if only the two sides could edge a little closer, he sighs. “We have to understand each other more. What we really lived, and live now.” I stumble out into a drizzly Sunday, slightly light-headed from the whisky and toting my copy – a parting gift – of Holiday in Seychelles.

Click here to change your cookie preferences