TikTok is one of the most prevalent social media platforms for trend-setting and trend-spotting – particularly within the relationship space. From trends and concepts like #DatingStoryTime to numbering the five stages of a relationship, TikTok is at the forefront of determining what’s hot and what’s not in the relationship world.

The newest trend to hit TikTok from a relationship trend perspective: beige flags.

Many would argue it presents similar features to pre-existing social media platforms like Instagram, Snapchat or Facebook. However, its ubiquity and popularity is often linked to its variety of content and distinct brand of weird humour echoed in many TikTok videos.

But TikTok is not simply fluff, it has increasingly become a space of contestation, negotiation and information of cultural, social and political norms.

Perhaps best described by Refinery29, TikTok has become a place “where we can learn about others’ morning routines, check out the latest headband hairstyles and follow creators who wear Victorian fashion every day” as well as “a place to exchange serious ideas … TikTok is helping people to question if they’re really straight, or just subscribing to ‘compulsive heterosexuality’”.

The latest TikTok relationship trend: beige flags. A trend which allows for both discussion and change in the relationship space but may also reinforce pre-existing boundaries and norms.

The term ‘beige flag’ was initially popularised by dating apps and referred to people who hadn’t put enough effort into their dating app profile, or presented as incredibly boring.

This included profiles which lent into generic hobbies like, “going to the gym” or a profile with a pedestrian series of pics, for example, a heterosexual standard, a single person holding a small dog.

In essence, the person wasn’t a “red flag” but a “beige flag” – for boredom. The term stuck briefly, but shifted quickly to another definition on TikTok.

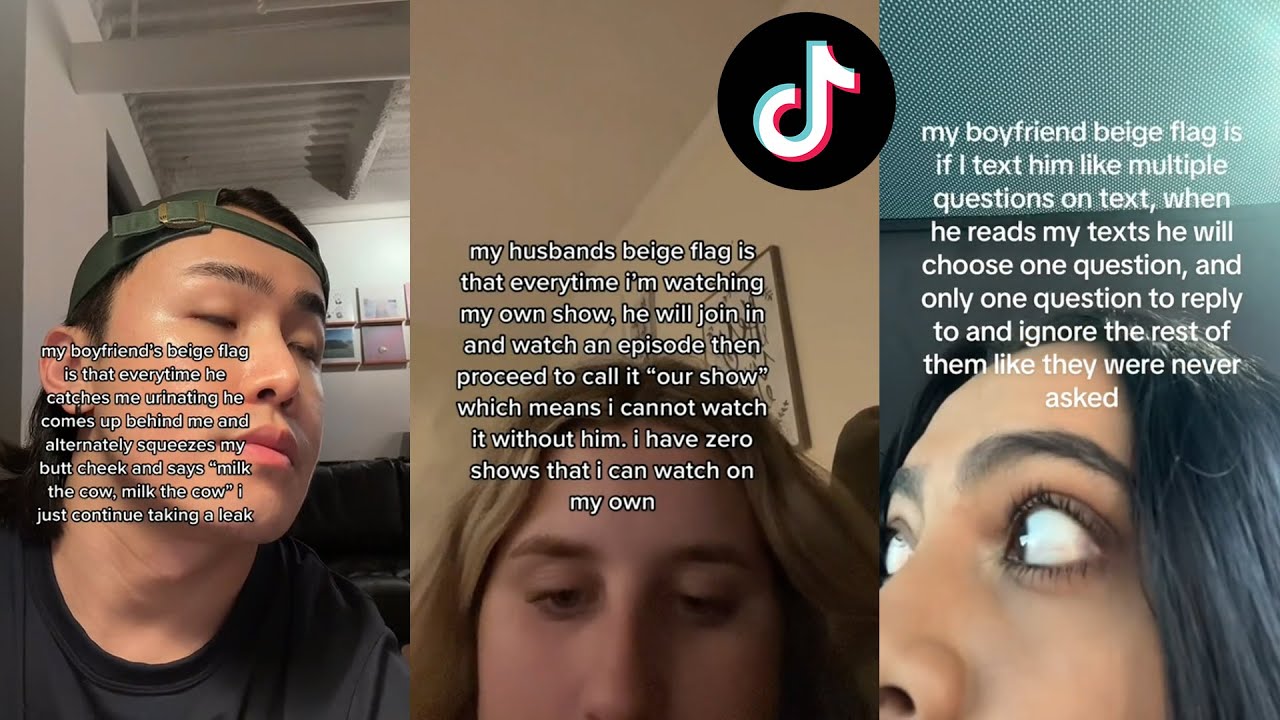

The TikTok beige flag definition refers to the odd quirks your partner may have – which bother you, but you are willing to accept. Examples include, extreme lateness, sucking tears off crying faces, assisting wait-staff if food is late at a restaurant or even tearing off holey underwear as a form of entertainment.

Those developing the content around beige flags are usually in a long-term relationship and the post is framed as satirical or humorous.

This follows trends like #DatingStoryTime, where users are encouraged to chronicle their dating wins and disasters in a vlog-like style. Some of these stories might include first date debacles on foods or drinks payment, strange and off-putting dating app Direct Messenger chit-chat and other spoof-like dating stories.

Again, this plays into a modern humour, a kind of jolly-absurdism, or merry-nihilism.

Simultaneously, these trends play into our desires, as human beings, to emplot ourselves into a masterplot. An overarching story which gives our lives shape, definition, a beginning-middle-end.

In this case, and via TikTok, users are playing into a well-known, white, western storyline: the romantic masterplot, and in particular the rom-com format.

Indeed, many of these relationship reels on TikTok rely on humour to entertain audiences, through beige flags or other intimacy trends, which are usually exaggerated for comedic effect.

By presenting these scenarios in a humorous way, TikTok can both entertain audiences and also help to normalise the idea that dating and relationships are processes fraught with potential missteps and pitfalls.

By laughing at these awkward situations, audiences may be more willing to accept that it is okay to make mistakes while dating and that these mistakes do not necessarily mean the end of a relationship. Also, that “odd” and “unusual” relationships are also relatively common.

With concepts like beige flags, #DatingStoryTime and other romantic trends, TikTok is pushing boundaries and leading us to question previously rigid dating norms and practices. It is also connecting like-minded people and establishing cultures of care among them.

Lisa Portolan is a PhD student, Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence

Click here to change your cookie preferences