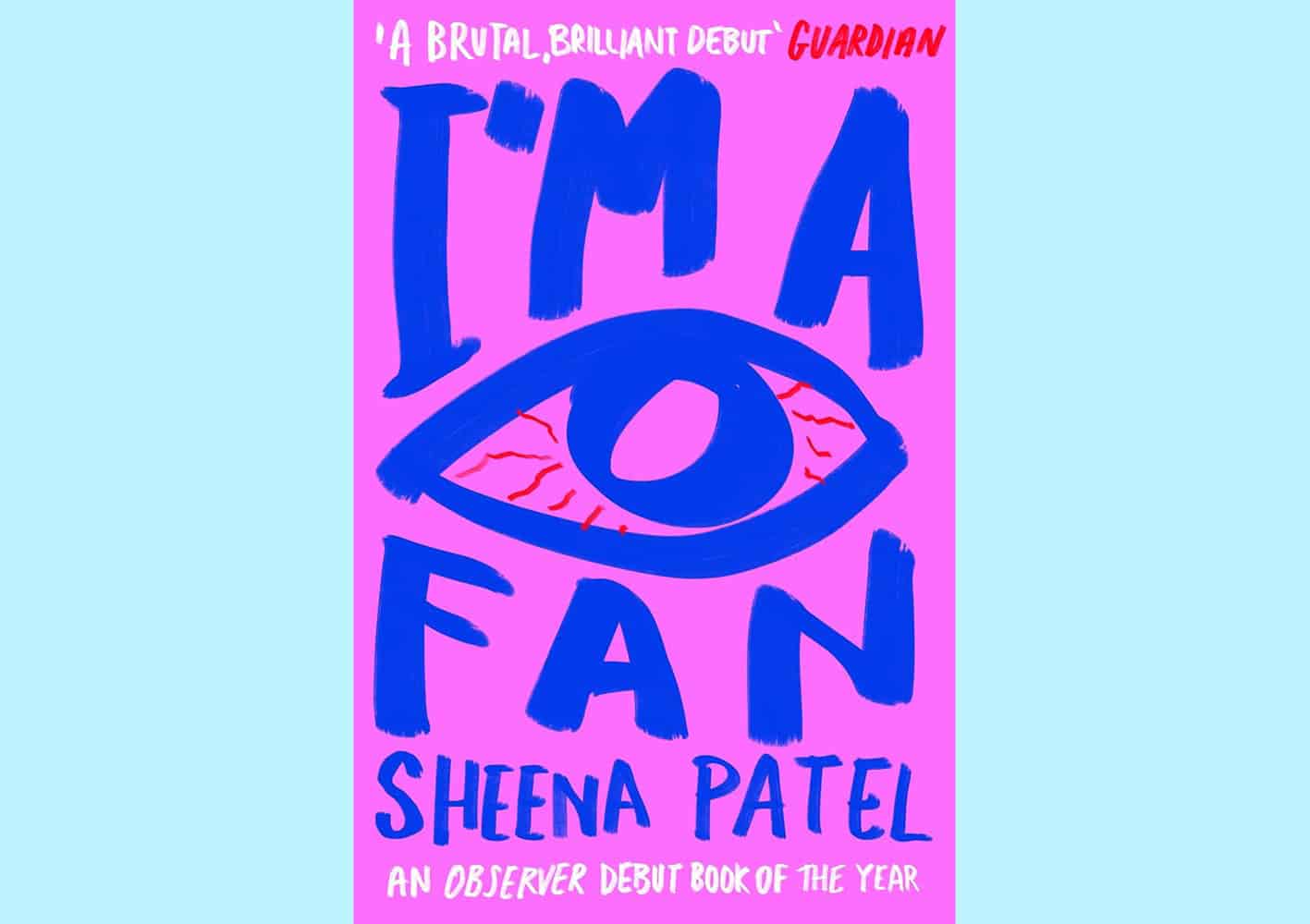

In The Merchant of Venice, Portia says that ‘I can easier teach twenty what were good to be done, than be one of the twenty to follow mine own teaching’. As Shakespeare well knew, ‘a hot temper leaps o’er a cold decree’, and in Sheena Patel’s debut novel, we get a tragi-comic view of a woman whose desires go against her better judgement at every turn.

Patel’s narrator is a second-generation immigrant and wannabe literary star who spends the novel obsessing over ‘the man I want to be with’ (a renowned artist) and ‘a woman on the internet who is sleeping with the same man as I am’ (a rich white American influencer who runs a disgustingly pretentious webshop). She longs for the former and yearns to triumph over the latter, seeing relationships as ‘sites of winning and losing – not connection and safety, but dominance and subjugation’. Deep down, though, the narrator knows she won’t win, and the moments of acknowledgement range in nature from ‘first of all i didn’t miss the red flags i looked at them and thought yeah that’s sexy’, to ‘In public we would all decry this behaviour, we would shout, dump him! to our friends’, and ‘I am not a main character in this ensemble romcom of betrayal’. Do these acknowledgements change her behaviour? We wouldn’t have a novel if they did.

We should, and do, feel bad for the narrator since the man she wants to be with is so obviously a manipulative manchild who leverages his celebrity into a network of exploitative relationships made up of women that form ‘a chaste harem, a supply of crazed female attention he likes to disturb when he’s bored’. But things are not so clear cut, because the narrator has her own fan – a devoted boyfriend – whom she publicly demeans and privately exploits, while the things she does to attempt to get into the life of the woman she is stalking are ethically unsettling, though very funny.

Ultimately, Patel’s novel poses unanswered questions that make us confront pervasive problems around celebrity, gender inequality, racism and social media. I’m a Fan is at its best when it keeps the reader balanced between enjoyment and unease, that ambivalence forming the most powerful critique of the structures the book aims to critique and mock. Where it occasionally fails is in the passages where the narrator expounds on these structures directly; Patel’s short, snappy chapters are not built to deliver theoretical insight, so these chunks fall flat. Thankfully, there is a lot more of the best than the worst, and the healthy dose of dissatisfaction with which I’m a Fan leaves us might just teach us ‘what were good to be done’.

Click here to change your cookie preferences