The eerie charm of the derelict Amiandos miner’s hospital where the past confronts the present and raises questions about the island’s future

I came upon it quite unexpectedly stopping to stretch my legs on a road trip while my children ran wild, soon returning with cries of “Mum, you’ve GOT TO see this!”

Dubiously I trudged after them, mindful of the late hour and the darkening sky. My reluctance rose as we approached rickety steps and a broken doorframe with graffiti of a naked female form with a giant mushroom head on the wall.

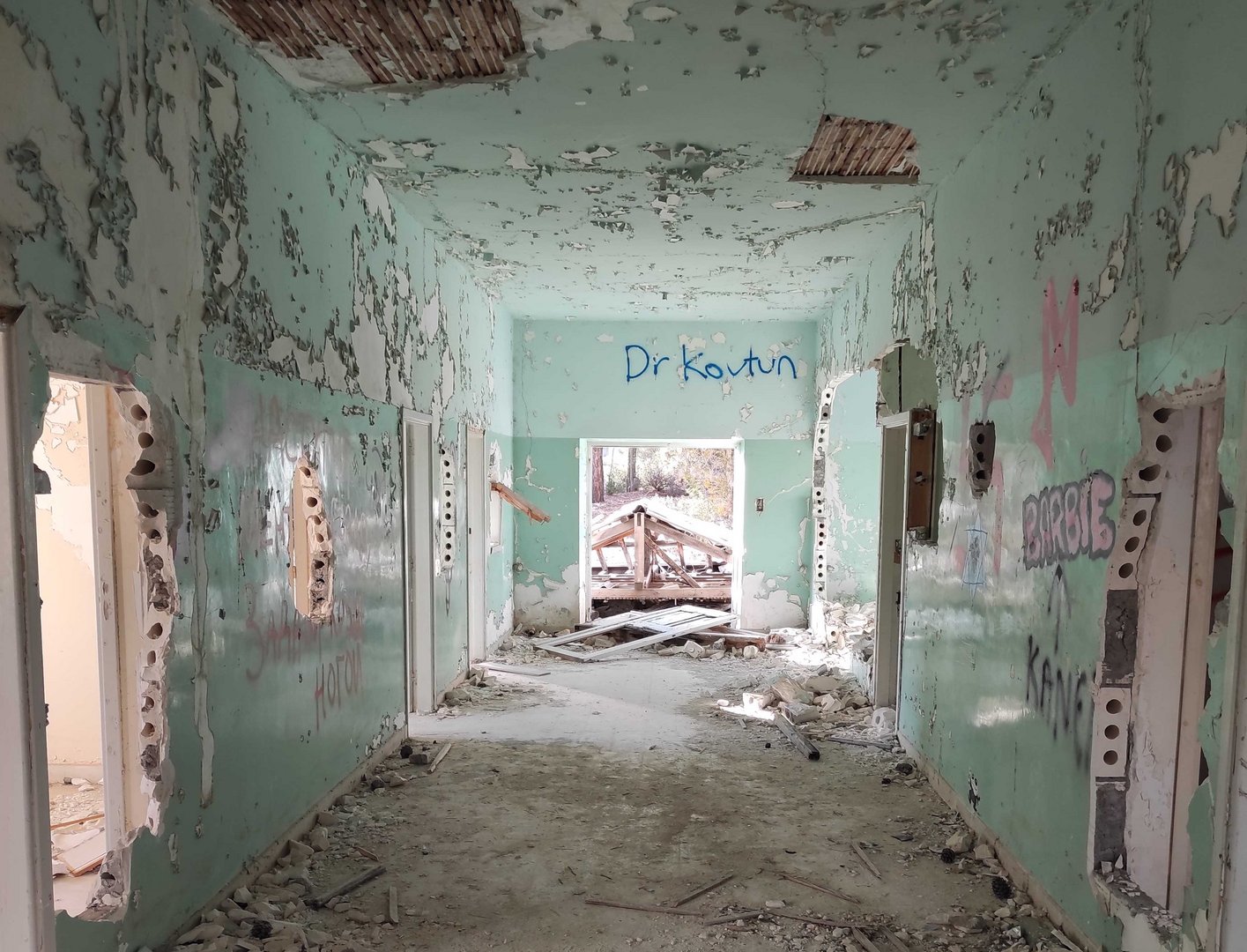

But my apprehension turned to wonder as soon as we stepped in. Floating over the piles of smashed wood, glass, brick and tile, the corridors, wards and operating rooms of the abandoned 1920s miner’s hospital unfolded before us.

Graffiti on the site

Derelict buildings are often graced with a haunting melancholic beauty, but the old miners’ hospital particularly so. Despite the walls being punctuated by dark-humour graffiti, the majestic tall windows opening to mountains and pines, aquatic blue-green hues of the decayed paintwork, and grand brick fireplaces greeted our intrusion, tantalisingly close to life.

Nurses in starched white uniforms, a woman in labour, a child with his leg in a cast, miners laid up from accidents or suffering through end-stage lung cancer from asbestos poisoning, flashed waif-like before my eyes.

Sheltering from drizzle at the village kafenio beside a giant copper heating contraption, like something dreamed up by Dr Seuss, Amiandos’ mukhtar Kriton Kyriakides quickly brought my romantic visions of the past to a prosaic end.

“There are loads of buildings, you should see the residences, walls this thick…they last forever. They could be turned into so many things…affordable housing for pensioners – or families, but no one cares, we barely get enough to cover our heating costs,” he bemoaned shooting me a glum sidelong glance.

The absence of state support, the ‘no one cares’ mantra, seems a staple among local community leaders island wide.

Exterior of the old hospital

Waving vaguely up the hill he continued, “They built us a brand-new multi-utility room…I’ve installed framed photos from the village history on the walls…but it stands empty and unused. There’s no buses, no proper roads…who wants to live here, who can work here?”

It is certainly easy to doubt the sincerity of the state’s oft-proclaimed slogan of “revitalising rural areas”, particularly when revitalisation seems confounded with the banal runaway development model to which we have sadly become accustomed (think: sterile squares, ‘bigger & better’ churches, more sunbeds, over-ambitious, tone-deaf installations, and of course, the national propensity for oligopolies).

We are indeed a far cry from a democratic social development policy – that some would say the country urgently needs – an ethos of building for the locals who live, work and pay their taxes on the island, rather than for rich absentees, foreign investors, or indeed, increasingly, digital nomads, earning their advantageous salaries in the northern EU states.

British nurse in 1920s (Ann Packer)

Delving into the mine’s history I was struck, however, by the timeless tenacity of this trope: locals, uneasily shackled to foreign investors, eking out a living quite literally from the island’s bowels.

Rights to the mine, which started as a small-scale operation in 1904, were first sold by the British colonial government to Cesar Trombetta, an Italian grifter who had become intrigued by rumours of vamvakopetra (‘cottonrock’) as the locals called it, in reference to the noticeable presence of asbestos fibres in it.

A year later Trombetta sold the rights to the Austrians who lost them in 1919, when the British seized the mine as an enemy asset in the wake of World War I, and auctioned them off to Limassol mayor Spyros Araouzos (grandfather of the island’s second president, Spyros Kyprianou).

The mine was subsequently sold to the Danes in 1936, who ran it for 50 years under the name Cyprus Asbestos Mines Ltd. In 1986 it was transferred to the Archbishopric of Limassol, under whose tenure it promptly went bankrupt two years later, following a steep decline in the use of asbestos as a raw material.

Boiler room in the hospital

The church body inherited the massive twin disasters of environmental destruction and health consequences to locals, while the Danes and previous stakeholders absolved themselves entirely of any responsibility, either towards land rehabilitation or reparations to residents for suffering caused from respiratory disease and lung cancer.

In its 84 years of operation the mine exported asbestos all over Europe and the USA, including to the UK, Denmark, Ireland and Sweden, which countries were also shareholders in Cyprus Asbestos Mines Ltd.

During this time Greek and Turkish Cypriot workers, travelling from as far away as Karpasia and Polis Chrysochous, including at one time around 3,000 women (some as young as 13), worked 12-hour or longer shifts, mainly in the summer months, digging up and processing about one million tons of asbestos fibre.

Women cracking rocks

In the words of Lawrence Durrell in his 1954 book, Bitter Lemons: “Mounds of white snow rise in every direction, filling the still airs of the mountain with the thin dust of asbestos. Men and women walked about in this moonscape, powdered into ghoulish insignificance by the dust…”

The workers first survived in makeshift shacks but in the 1920s a British architect was tasked with designing a “congenial” housing complex, which included shops and 60 residences, across the road from the hospital. Most of these, like the hospital, still exist, crumbling and vandalised.

A fireplace in the old hospital

Over time the hillsides and valley were denuded, a huge crater formed, ground water, the river Kouris and its dam, polluted. Mountains of debris, a total of 130 million tons –for a return of less than 1 per cent extractable material – were dumped in the vicinity, making the area unstable and prone to landslides and flooding.

Restoration works on the hillsides by the state have been ongoing for close to 30 years, while the mechanised tools introduced in the 1950s were sold for pennies as scrap metal, and the uninhabited buildings stand unused, locked-up in a bureaucratic limbo between government services.

Nothing much remains linking the ageing, nowadays agricultural, community with the island’s urbanites – other than a reference point, obscure to most, in the hippest part of Limassol.

This is the so-called Enaerios (aerial): the terminus of a 30km airlift line, which at one time transported 180 wagons every 90 minutes high above the pines, from Amiandos mine to the old port, and on which, according to lore, local urchins sometimes rode as stowaways in wagon #75, the postal box.

Aerial lift from mine

Amiandos as a whole stands out as a richly instructive and cautionary tale on the implications of ill-informed development, technological innovation adopted solely on fleeting profit-based criteria, and lack of grasp of the collateral damage inflicted on the local population as a result.

One wonders whether similar processes are currently in sway in a different iteration, with all the unchecked developments on both halves of the island, another kind of digging into the bowels of the land, planting inert concrete and water-greedy lawns where rich life-giving beauty once flourished of its own accord.

Will the currently touted state and private development projects (highways, marinas, hotels, large sporting facilities), usher in a genuine “revitalisation” or do they herald the last nail in the coffin of what is actually a culture and a land in its death throws?

Click here to change your cookie preferences