Opinions on the possible Cyprus solution remain as divisive now as they did 20 years ago

Next week marks the 20th anniversary of the referendums on the Annan Plan, the events of that period seared into the memory of those who lived through it. And yet two decades later the visceral, passionate disagreements on ‘what might have been’ have hardly abated, as the Cyprus Mail discovered speaking with proponents of the two camps.

The separate simultaneous plebiscites held in Cyprus on April 24, 2004 resulted in the majority Greek Cypriot population voting down the UN plan (75.38 per cent against), whereas the minority Turkish Cypriot population voted for it (64.91 per cent in favour). The turnout was high: 89.18 per cent for the Greek Cypriots and 87 per cent for the Turkish Cypriots.

The political leaders of both sides – Tassos Papadopoulos and Rauf Denktash – had campaigned for a ‘no’ vote, but the moderate, Turkish Cypriot leader in waiting Mehmet Ali Talat had campaigned for a ‘yes’, strongly supported by Turkey.

In exit polls on the day, 75 per cent of the Greek Cypriots who voted ‘no’ cited ‘security concerns’ as the main reason for their choice. Turkey had not only once again been given the right of unilateral military intervention, but would be allowed to keep a large number of troops in Cyprus after a settlement, whereas the national guard was to be dissolved.

We found an item published by news outlet Stockwatch and dated March 8, 2004 – a little over a month before the referendums. It reported that three opinion polls conducted on the Greek Cypriot side had shown opposition to the Annan Plan ranging from 53 to 62 per cent.

Evidently in favour of the proposed settlement, the author tries to inject a sense of urgency by underlining the gravitas of the moment – an opportunity not be missed and so forth.

“All that’s left is to convince the directly affected Greek Cypriots,” the author wrote. He was to be sorely disappointed.

To get a handle on where we’d be now had the UN blueprint passed, we can look at its key provisions. You can read the full text of the fifth and final version here.

In brief: the Annan Plan of 2002 to 2004 was arguably the UN’s most concerted attempt to reach a federal solution to the Cyprus problem. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan presented a first version of his plan in November 2002 and a fifth and final version in March 2004. He had wanted the final text to emerge from negotiations between the two sides but, amid continuing deadlock, finalised the text himself.

Annan expressed dismay at the Greek Cypriot ‘no’ vote, as did Washington, London and Brussels. Cyprus still entered the EU a week later on 1 May 2004, but with only the Greek Cypriots enjoying the benefits of full membership.

The plan proposed the establishment of the United Cyprus Republic, “an independent state in the form of an indissoluble partnership, with a federal government and two equal constituent states, the Greek Cypriot State and the Turkish Cypriot State”.

The state would have a single international legal personality and single sovereignty. People would hold two citizenships: that of the common state and of the component state in which they lived.

As for governance, the new state would have a federal parliament comprising two houses – a Senate and a Chamber of Deputies. Executive power would be vested in a presidential council with six voting members. No less than one third of the voting and non-voting members would come from each constituent state. No less than a third of members from each category would be Turkish Cypriots.

The presidential council would be elected on a single list by special majority in the Senate and approved by majority in the Chamber of Deputies for a five-year term. The presidential council would try to reach decisions by consensus.

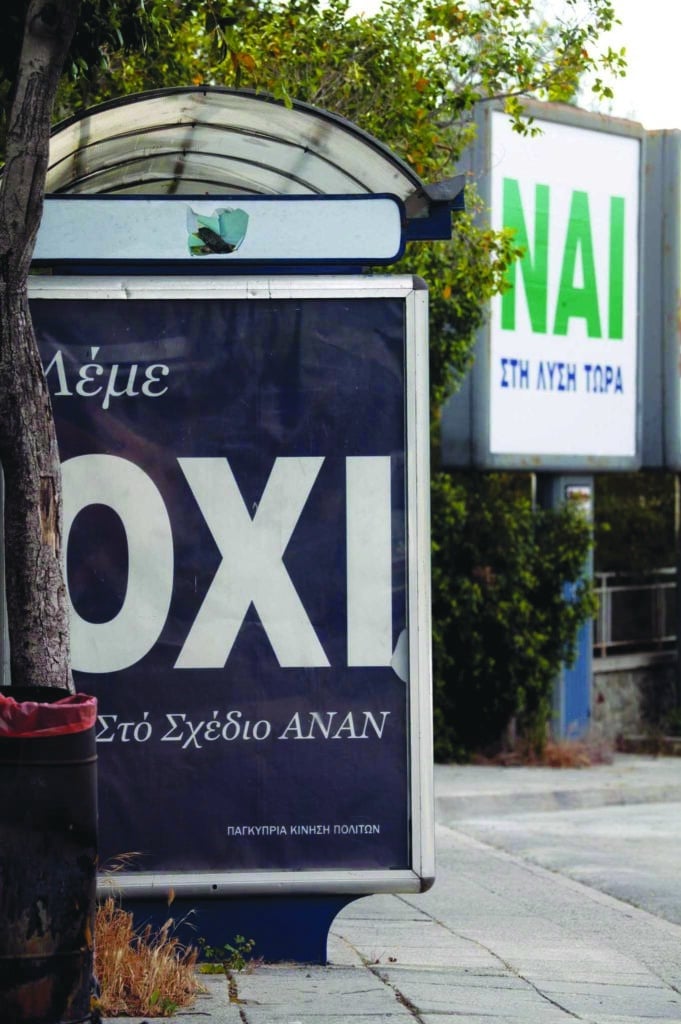

Yes and No billboards in the run up to the referendum

On territory, there would be significant territorial adjustments in favour of the Greek Cypriots. The Turkish Cypriots made up 18 per cent of the population at the time of the 1974 invasion but were left in control of 36.2 per cent of the island’s territory. Their territorial share would be reduced to 28.5 per cent. This would take place in six phases over a 42-month period, starting 104 days after the agreement came into force.

Regarding security and guarantees, the three 1960 Treaties of Establishment, Guarantee and Alliance would stay in place. Britain, Greece and Turkey would remain as guarantor powers.

And there would be a phased demilitarisation of Cyprus. All Cypriot security forces would be disbanded while Greece and Turkey would each be allowed to keep up to 6,000 troops in Cyprus until 2011. That would be reduced to 3,000 each by 2018 or earlier if Turkey joined the EU before that date.

After that, numbers would be scaled down to the original 950 Greek and 650 Turkish troops envisaged under the 1960 Treaty of Alliance. This would be reviewed every three years with the aim of an eventual total withdrawal of all Greek and Turkish forces.

As for the Turkish settlers, under a complex formula 45,000 would remain in the north. Today their numbers can only be guessed at, but the consensus is that they number well over 100,000.

Asked to look back and assess the ramifications of rejecting the UN plan, lawyer Christos Clerides – then as now an ardent opponent – doesn’t pull any punches.

“A major reason the plan got rejected is because there was no way to ensure that what was agreed, would be implemented. The UN would not guarantee any of it,” he asserts.

“What does that mean? That actual implementation would be highly doubtful. This applies to everything – including the return of land under the agreed schedules.”

Another flaw for Clerides has to do with the fact that in the new state no decision could pass unless Turkish Cypriots also agreed. This could potentially paralyse everything – the government, parliament and the judiciary.

“So at no level of governance could a decision go through without the endorsement of the Turkish Cypriots – leading to an impasse.

“That could have led to a collapse of the state, and then with mathematical certainty we [the Greek Cypriot side] would be led to seek international recognition as a constituent state, since the Republic of Cyprus would no longer exist. Let that sink in.”

Bottom line for the former head of the bar association: “If Annan passed, today we’d be in far worse shape.”

Pressed on how confident he is that Ankara would not honour the agreement, again he is direct: “Turkey is a bad-faith actor. Look at their trajectory on the Cyprus issue after 2004…more and more hardline.”

We put these arguments to the other camp – and drew a hurricane of a response.

Praxoulla Antoniadou, former commerce minister (2011 to 2012) and chairperson of the United Democrats party, proceeded to excoriate the ‘rejectionists’.

“Look, this talking point of theirs that the Turkish side can’t ever be trusted…that’s their fallback position. So if you can’t trust the Turks supposedly, what’s the point of talking anyway?”

The former politician counters that the deal would have been signed off on by the UN as well as the three guarantor powers.

“Did it have a weakness in terms of the implementation mechanism? Possibly yes. But this is the familiar excuse of those opposed to the settlement. So I ask them: do you prefer the current state of affairs, the country divided, Turkish troops in the north, the influx of Turkish settlers?”

Antoniadou is equally empathic, but coming at it from the other end – the Annan Plan was an opportunity not to be missed.

“With a reunified country, the economy would have boomed. The settlers, those who remained, would be eventually assimilated. Next, illegal immigration would be brought under control, as opposed to now with the porous Green Line. Then think about the construction burst in the north after 2004. Also, the so-called ‘Islamification’ of the north, which even the secular-oriented Turkish Cypriots complain about.”

Antoniadou also shreds the other point raised by the naysayers – concerns over power sharing and smooth governance.

“Do they forget the 1960 constitution also provides for sharing power with the Turkish Cypriots? This kind of arrangement is nothing new, but they act as if it is.

“What it boils down to, is that there are those quarters on our side who simply don’t want to share power. Essentially they want it all. The term ‘political equality’ is anathema to them. But the UN has defined it as effective participation in decision-making.”

The ex-minister goes on to warn the ‘rejectionists’ that even they will come to rue their attitude.

“At some point, I think the Turkish Cypriots – as a community, not as individuals – will claim their full rights as citizens of the RoC. That means they get to participate in power structures. And then what? Power sharing in the south, while the north is overrun by Turkish settlers.”

Asked if there’s still a glimmer of hope for a settlement, Antoniadou says yes.

“There’s always the possibility, however remote, that [Turkish Cypriot leader] Ersin Tatar might back off his demand for a two-state solution. Remember, that happened with Rauf Denktash too.

“So we’ve got to be ready for that eventuality. But will we?“

Click here to change your cookie preferences