By Catherine Strong, Bianca Fileborn and Paige Klimentou

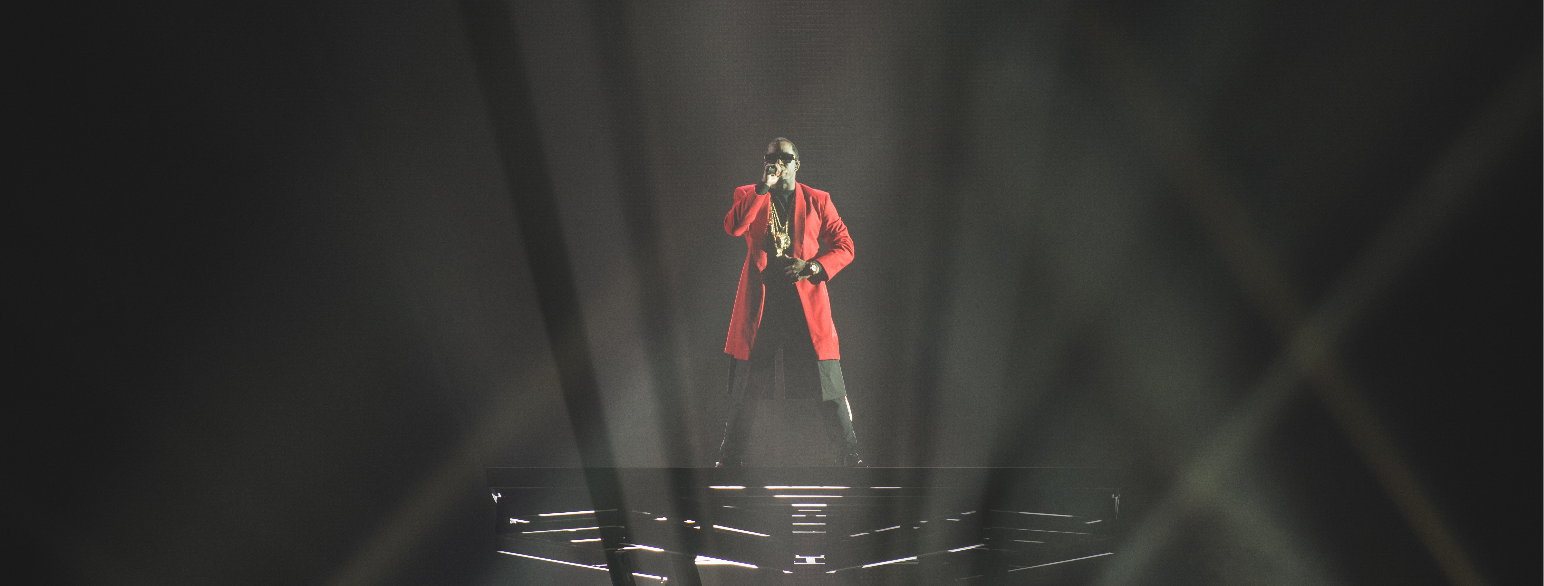

The perennial question of what to do with musicians and their work when they are found to have been abusive has arisen again this week, as distressing video footage of rapper Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs assaulting his then girlfriend Cassandra Ventura in a hotel in 2016 was released by CNN.

Last year, Combs settled a lawsuit brought against him by Ventura, which accused him of sexual and physical violence over the course of more than a decade.

Following the video’s release, Combs posted an apology video in which he states “My behaviour […] is inexcusable. I take full responsibility for my actions in that video”. This is at odds with a 2023 post in which he wrote “I did not do any of the awful things being alleged. I will fight for my name, my family and for the truth”.

But why does it matter if artists are abusers? And what impact does it have on fans when these cases emerge?

High-profile cases can play an important role in shaping community understandings of gender-based violence, although unfortunately commentary often reproduces problematic understandings about men’s violence, such as calling sexual violence “sex”, or by blaming the victim for the violence they experienced.

At a time when gender-based violence is at crisis levels in many places, how Combs’ actions are framed, and society’s subsequent response, can send a powerful message about our tolerance of men’s violence, and whether men who use violence will be held to account for their actions.

There is a long history of musicians being implicated in gender-based violence and domestic abuse, but nevertheless being protected by the industry.

Decades ago, abusive behaviour towards women was often hidden behind ‘sex, drugs and rock’n’roll’ mythologies or excused as part of their artistic ‘genius’.

In the #MeToo era, we have seen many women come forward with experiences of abuse, assault and sexual harassment, often committed by our favourite artists, directors or actors.

This has not stopped abuse from happening.

Some fans argue they can separate art from an artist’s alleged misconduct, whereby an artist’s actions will have little to no bearing on how the music is consumed. Allegations, no matter how well supported by evidence, will not affect their fandom or relationship to the music.

Other fans see the artist and the art they create as inseparable. They will no longer listen to their music, and will get rid of any merchandise and memorabilia.

A fan’s response may also depend on how important it is for them to be seen as an ally for victims, as well as their own social position in relation to both the victim and perpetrator.

Research on fans has found that race and musical genre play a role in how perpetrators are framed and what the fans’ reactions to their misdeeds are. Hip hop fans’ understanding of the struggles of black artists and the ways the media frames black men as more violent than white men can lead to a sympathetic, if not entirely forgiving, approach to their actions.

These perspectives suggest holding an artist to account does not necessarily entail a punitive response.

As fans, we have power to shape the narrative. Do we respond in a way that minimises and excuses the actions of men who use violence and the industry that enables them, or act in solidarity with survivors?

A refusal to listen to the music of abusive artists can be a powerful political response. However, it’s clear many fans do continue to listen. If we do continue to listen, we have an ethical obligation to listen with an awareness of the broader social and political context in which violence is perpetrated.

We must listen with an obligation: not to excuse or ignore the violence of these artists; to meaningfully listen and engage with the experiences of survivors; and to challenge and disrupt the complicity of the music industry.

This can be done by incorporating the stories of survivors into the histories of these artists, an important first step in ensuring these misdeeds are not so easily forgotten.

We can still recognise an artist’s work or achievements, but at the same time ensure they remain accountable for their actions.

Catherine Strong is Associate Professor, Music Industry, RMIT University, Bianca Fileborn is Associate Professor in Criminology, The University of Melbourne and Paige Klimentou is Sessional Lecturer, Music Industry, RMIT University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence

Click here to change your cookie preferences