THEO PANAYIDES joins an audience with the unshowy Hollywood star who describes himself as a plodder with a lot of interests, but is always present

It’s around 12 midday in the foyer of the Cyprus Theatre Organisation (Thoc) building in Nicosia, and one middle-aged chap in a white shirt and navy-blue jacket greets another warmly.

“Never left the office at this time of day before!” says the first man.

“Yeah, but it’s worth it,” replies his friend – then lowers his voice briefly to talk, I assume, about business.

My own acceptance message (received after registration and emailed approval “on a first-come first-served basis”) reflects the gravity of the occasion. “Please present the QR Code upon your arrival,” it instructs. “Cancellations must be received in writing by 10:00am.” The message sender appears simply – and a bit forebodingly – as ‘MALKOVICH’.

We are indeed here for a one-hour conversation with actor and director John Malkovich, ‘we’ being 160 people in a packed auditorium. Open Talk with John Malkovich: Art, Culture and the Economy is the name of the event – part of the ongoing Cyprus International Theatre Festival, which brought him over for two performances of a piece called The Infamous Ramirez Hoffman at the Pattihio in Limassol. This is his only brief appearance in Nicosia, hence the excitement.

That said, this Thoc event wasn’t part of the deal. The plan, as originally scheduled, was for Malkovich to speak in the atmospheric environs of the deserted Berengaria Hotel up in the mountains. Alas, that got changed or (more likely) didn’t happen – so here we are at Thoc, ‘we’ including many of the capital’s great and good.

Those two business types in navy-blue jackets are typical of the audience. There’s a smattering of bohemian-looking theatre people and garrulous Russians – but I also recognise a prominent tax accountant, and a former minister. The women sitting behind me are cinephiles (they mention Lars Von Trier and Kore-eda), but the gentleman to my left is a medical physicist, while the one on my right works in maths and statistics.

Neither of my neighbours has ever seen Malkovich on stage, at the Pattihio or anywhere else. They only learned of the event two days ago, through the IMH mailing list – IMH being a big event-management company that works closely with the business community, and presumably took on the organisation.

All this is relevant – not just to set the scene, but also because of the type of character John Malkovich is: a cultured, unshowy 70-year-old with an affable but rather dry style. “Malkovich talks more slowly than anybody I know,” wrote Simon Hattenstone in an excellent profile in the Irish Times four years ago. “His language is flat and restrained – almost self-consciously untheatrical – even when telling the most dramatic stories”. I’m not sure what the crowd are expecting, but a raving raconteur the man is not. The event is free – yet you still have to wonder if the navy-blue brigade feel they got their money’s worth.

Festival director Alexander Weinstein gives a brief introduction – then it’s time for the man himself: dressed all in white with orange-brown sneakers, silver-goateed, bald as an egg. He holds a cup of coffee but doesn’t drink from it, and later puts it down on the floor. His legs are crossed, his arms lightly folded. He’s a celebrity – twice Oscar-nominated, not to mention being perhaps the only actor ever to star in a fictional film (Being John Malkovich, from 1999) with his name in the title – but his style is languid and matter-of-fact. He goes slow, and tends to aim deep.

“What is ‘John Malkovich’? What does that even mean? It’s just a name,” he muses when Weinstein asks about the 1999 movie. “I’m not a public person, actually. I mean, of course I am,” he checks himself – “but I don’t have any concept, or interest in that. I never have, and I never will.”

“My mother referred to me as a plodder,” he tells the crowd. “I think it’s absolutely true – that’s who I am.” He illustrates with his hand, one finger plonked down slowly in front of the other. “Little by little, make it better. Little by little, make it better.”

He’s done a lot in life, plodder or not; his talk is packed with random nuggets. He’ll come out with things like “I was in fashion for many years” (it’s true; he created his own fashion brand in 2002), or “I was directing a play in Latvia last year”. The subjects of his stories range from Portuguese film director Manoel de Oliveira (the world’s oldest filmmaker, “still working every day when he passed away at 106”) to writer Paul Bowles, whom he met while filming The Sheltering Sky. “I do a lot of collaborative projects,” explains Malkovich. “I don’t rule out any field of interest. I have a lot of interests.”

He even worked briefly on developing a film about the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, though it was years ago and he can’t recall all the details. “Cyprus is never really talked about anymore,” he sighs in passing, unaware of the dagger he’s just plunged into the collective heart of his audience.

He was always a bit detached, not entirely mainstream. Politically he remains “a ferocious anti-Communist,” as you’d expect from an American born in 1953 – but he also collaborates regularly with Russian artists (Ramirez Hoffman paired him with pianist Anastasya Terenkova), a risky thing in the current climate. He lived in France for several years with second wife Nicoletta Peyran – his first marriage fell apart over an affair with Michelle Pfeiffer, his co-star in Dangerous Liaisons – a former filmmaker who’s now an academic and “China scholar”. He’s even said that he feels like he must’ve been Japanese in a previous life – though that’s more to do with work, he explains: “Details are everything, and that’s something I greatly admire in that culture”.

Easy to imagine that John Malkovich’s greatest gift as an artist is indeed for a kind of Japanese fastidiousness, patiently working out details (little by little, making it better) – and something else too, a gift for existing in the moment. “I don’t have much in the way of talent,” he muses, “but I have a talent that not many people have: I’m actually where I am. That’s very helpful for work. And it’s not bad for life, either.”

That’s why he’ll always take the theatre over cinema – because, as with life, “you had to be there”. Theatre is ephemeral, like life; it doesn’t last, except in the viewer’s memory. “That doesn’t exist in the cinema – because the cinema is,” he hesitates, “a plastic form. It’s not living. It’s dead. Every instant is manipulated 100 per cent… And there’s beauty in that,” he admits, “great beauty. And some people love that it’s lasting”. He shakes his head: “I don’t need it to last”.

A question from the audience: a young man, apologising for the “personal” nature of his question. He loves theatre, says the boy, and he’s “reaching an age where I need to come to a decision” – but isn’t a career in the theatre too risky? How did Mr Malkovich feel when he decided to become an actor? “Did it feel like a risk you were taking, or did it feel like it was the only possibility?”

Malkovich looks a bit uncomfortable, whether because he’s not sure how to approach the conversation (neither of his own two kids are actors) or because he’s even less of a mentor figure – at least to strangers – than a raconteur. “Y’know, my opinion is – just do what you love,” he shrugs. “Certainly, I didn’t even think about it. I’m not very profound. Some other idiots asked me to start a theatre with them” – that was the legendary Steppenwolf Theatre Company, in Chicago in 1974 – “and like an idiot I said okay. And life went on. I never even thought about it.”

Did the young man hope for an inspirational pep talk, like in the movies? Did the navy-blue jackets hope for rollicking tales and Hollywood gossip? Maybe – but that doesn’t seem to be who John Malkovich is. He’s a doggedly honest person, a worker, a plodder – a man who lives for art and just lives, not really caring for profit or consequence.

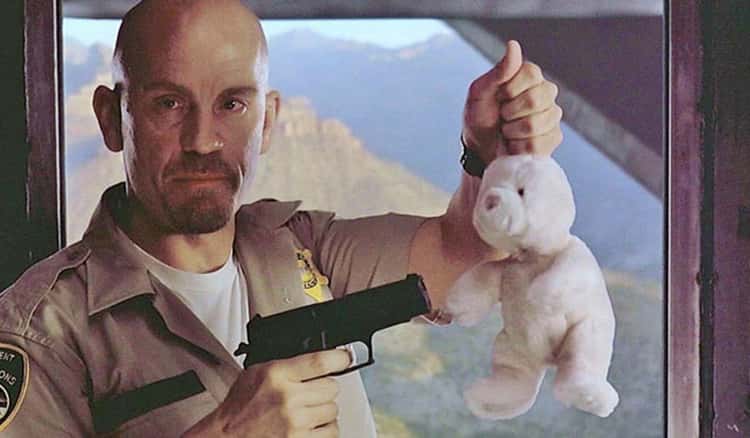

Another question from the audience. “It’s pretty cool to meet a hero of the movies you love,” gushes a fan – and mentions Con Air from his childhood, the 90s blockbuster where Malkovich played a psycho called ‘Cyrus the Virus’.

The actor tries to be gracious – but it’s clear his heart isn’t in it. “In the movies, you’re a product. That’s how movies work, because it’s a business.” He does play lots of psychos and sinister types – but it’s not by choice, that’s just what he’s offered; the Malkovich Touch, if you will.

“A lot of times you’re chosen for bringing certain qualities to something that doesn’t have them… Or doesn’t know what it needs, or doesn’t know what it wants to be. So sometimes in my career, when – uh, maybe they want some undefined element that they can’t really articulate, then they ask me to do it. And if it’s something like Con Air…” Malkovich pauses, then chuckles as if to say ‘C’est la vie’: “You know, it’s Con Air!”.

It’s odd, in a way. After all, his film career isn’t incidental, it’s a major part of his work. Maybe he feels a need to play it down in order to be faithful to theatre, his first love. Or maybe he’s actually closest to Osborne Cox among his movie roles, the supercilious spy he played in the Coens’ Burn After Reading – only nicer, and a lot less foul-mouthed.

Or maybe there is indeed something that repels him slightly about cinema: its slickness, its inhuman perfection – what he called its ‘plastic’ quality. Another question asks about AI, and elicits a passionate response: “When AI can paint The Night Watch, I’ll wake up,” he declares – adding Mozart, Schumann, Dostoyevsky to the list. “But I don’t think that’ll ever happen.”

“People are – imprévisible [unpredictable],” he goes on, bursting into French in his enthusiasm. “People can do spectacular things. Beautiful things. Yeah, they’re imperfect vessels, of course – and I wish people would get used to that. Just accept it. Nobody’s auditioning for Christ…

“But humankind has made incredibly beautiful things. And I don’t see anything beautiful that AI has made.”

Is that why they left the office early, the doers and business leaders and high achievers – to listen to an anti-tech diatribe from an old-school aesthete and reluctant movie star? Probably not.

Still, the applause is real, and they seem quite happy afterwards: back again in the Thoc foyer, sipping prosecco and posing for selfies with the actual John Malkovich.

Click here to change your cookie preferences