A family forever torn from their beloved village of Akanthou after August 14, 1974

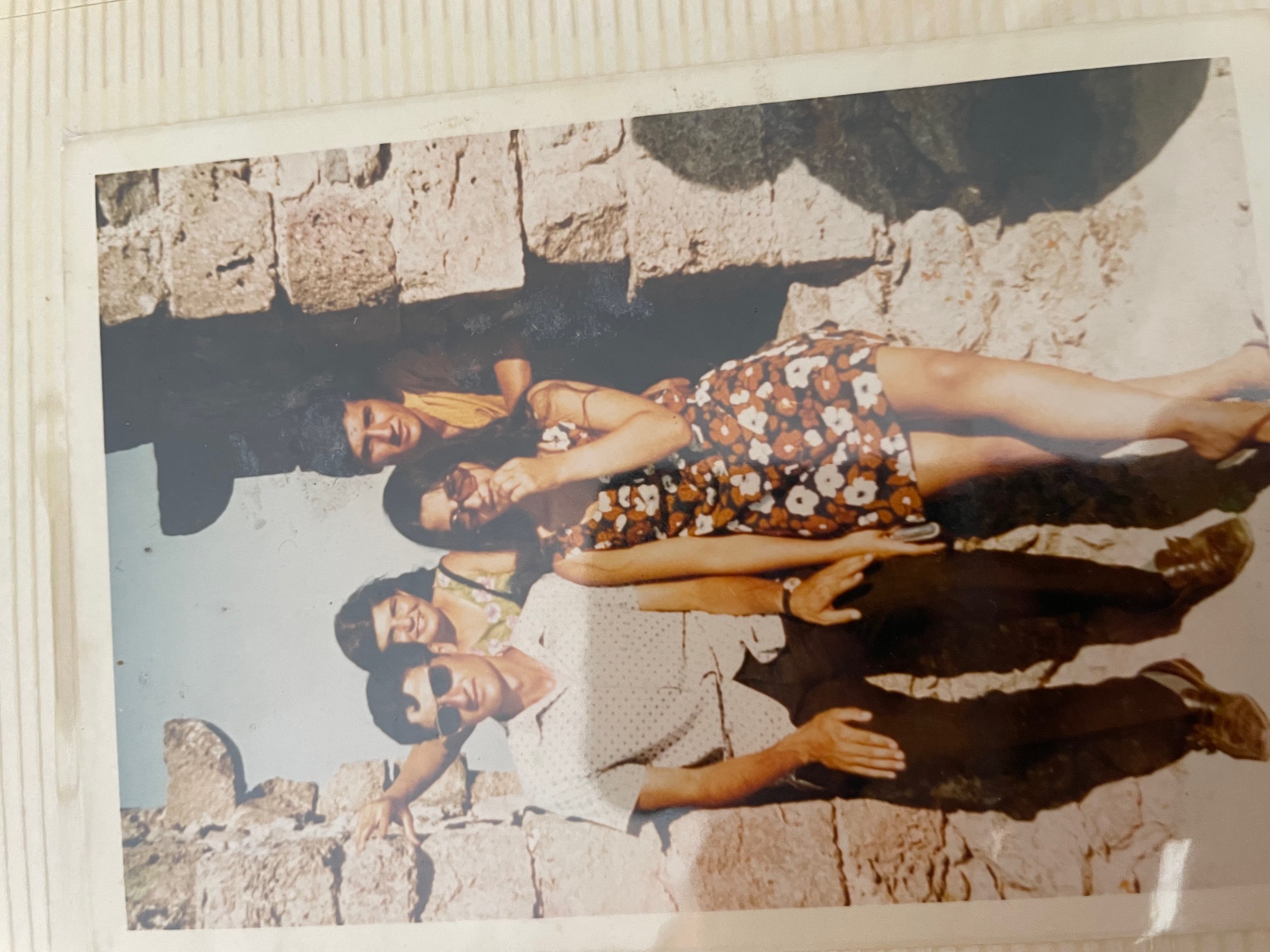

This is the story of three sisters, forced abroad by an invasion that coloured the rest of their lives and left them haunted by the memories echoing down 50 years.

In the days after the second stage of the Turkish invasion on August 14, 1974, as Turkey rapidly expanded its occupation, Maria, Katerina and Christina were forced from their village of Akanthou, which was nestled in the foothills of the Pentadaktylos, bordered by Cyprus’ northern coast.

These three women still carry the scars of separation and fear, but circumstances necessitated survival, forcing them to learn new customs and languages, and adjusting to building futures in their adopted homes.

Meanwhile, the story of Akanthou remains locked in a box of longing and nostalgia.

The three sisters fondly remember their modest home, where they lived with their four other siblings and parents amid their fields, collecting carobs, cultivating vegetables and fruit and tending to their sheep.

Katerina remembers vividly bathing the sheep in the sea.

The village comes alive as she talks about her father grabbing the first of the herd and jumping from a cliff into the ocean, leading all the other sheep to follow.

“I was always adventurous,” she said describing how she used to enjoy diving from the same sea cliffs and swimming to shore.

Maria, the oldest girl of the seven siblings, says life was difficult for farming families, but a simple life kept them all close and happy.

She speaks of the summer visits from her uncles, who had gone abroad in the 50s.

“Our uncle once took us to Kantara castle in his tractor!” Maria says, recalling one outing with her cousins a few years before the invasion. “I remember climbing the mountain roads in that tractor, travelling along to see the beautiful views of the surroundings below.”

Christina has the shortest memories of the village, being the youngest of all the siblings and only 12 when the invasion took place.

She remembers playing with dolls with other neighbourhood girls, helping in the fields, and attending classes at the primary school.

“School was always an event for the children back then,” she says, explaining that all the neighbourhood kids gathered and would race their donkeys to school.

“I always got to ride the donkey, as I was the youngest and smallest.”

Katerina had actually left the village before the war. She was visually impaired and attended the School for the Blind in Nicosia from the age of 12.

She then worked at a clinic in the capital and lived through all the troubling times from the coup on July 15, 1974, until the second invasion on August 14.

Maria had been an apprentice to a seamstress in the 60s in Nicosia as well, spending summers in Akanthou, and eventually moving back before the Turkish invasion.

Christina was just a child.

Katerina told the Cyprus Mail she had an inkling of the second wave of the invasion from rumours in Nicosia at the time, and desperately tried to plead with her family to leave.

She had seen the injured from the July 15 coup and from the first leg of the Turkish invasion on July 20, lived through the fighting, heard the shots ringing back and forth in the capital.

“A bullet narrowly missed me,” she said about the fighting taking place in the capital near the clinic she worked at in Lykavittos.

“There are images that are too painful for me to remember, and just thinking of them still shocks me,” she said, playing out the scene of one injured man in the clinic, whose hand had almost been completely torn off.

On August 14 itself, Maria and her mother, Chrysi, had been separated from her husband and four of the children, including Christina.

“I remember how the Turkish soldiers killed a Turkish Cypriot worker in the village, who had been tending to the animals of the Greek Cypriots.”

They were bused out of Akanthou with other villagers and taken to Gypsou where the women were separated from the men and women from different villages were kept in homes there.

“It was all so confusing. We had no idea it would be permanent,” Maria says.

Just as horrific, Maria describes the first nights in Gypsou, and one in particular.

“My mother and I heard screams coming from a house next door,” she says.

The Turkish soldiers had gone in and were attempting to harass the women of another village, she says, remembering her mother and all the other older women throwing themselves on top of their daughters to protect them.

The next day, the women in the entire village were silent not talking or looking at any of the soldiers.

When asked by a new officer who had been brought there what happened, one woman finally spoke up. “The guards that had attempted to harass the women were grabbed on the orders of the officer and beaten.”

Maria and her mother stayed there three months until finally being taken by the Red Cross to Nicosia, where they were eventually reunited with their family.

Meanwhile, 12-year-old Christina remembers being told to leave Akanthou immediately as the Turkish army was approaching.

She, her father Michalis, and her three other siblings took their sheep and left the village on foot.

“I remember the bombings and planes flying overhead,” she says.

They ducked behind trees and hid in buildings for cover on their four-day journey across the island.

On the fourth day just as they were about to cross from Dherynia, they were caught.

“The soldiers lined us up, beat the men, the sheep scattered, and the Turkish army clicked their guns at us,” she says. She remembers the terrifying moment when her dad was loaded in a van after being beaten and taken away.

“They were all lined up and led away by the army, which tied the men’s hands, blindfolded them, and threw them into a truck.

The children were all rounded up and dropped off near an area by Dasaki Achnas.

“We walked for a while until we reached the UN camp,” Christina remembers.

There they found one person from their village, got some clothes and shoes, as theirs had been torn fleeing Akanthou. They were eventually able to make their way to some family members, where they stayed.

Eventually, after months of anxious waiting, all the family was able to reunite in Nicosia, where they stayed for two years in Chrysalliniotissa.

“It was a huge party and we were so happy after all being together,” Katerina explains, who had spent the second-leg of the invasion outside the Red Cross asking about her family’s fate.

She cries as she remembers the day when she was told all her siblings had made it out and they were with other uncles.

Christina recalls the family being reunited, and how battered and shaken up her father was coming out of the Red Cross centre at the Hotel and Catering School during a prisoner exchange.

When Maria and her mother arrived from Gypsou shortly before Christmas, she remembers not knowing how to react standing in the churchyard of Chrysalliniotissa after school.

The family ended up going to a home and piece of land the government provided for them in the Turkish Cypriot village of Avdimou.

“We always felt like strangers there,” Maria and Katerina describe, explaining the village that had been pillaged by other Greek Cypriots, who left many houses also damaged by fire in their wake.

Along with the pillaging, many of the houses had been burned, and left for refugees to take on.

“I remember the mice and insects crawling around in the night,” Christina says. Her family had moved into a half-built home, without doors and windows.

And then came another traumatic separation.

Katerina was the first of the children to leave.

“I was made a refugee twice,” she says, first taking a job as a caretaker and maid in Rome.

She arrived there in 1977 not speaking a word of Italian, and not having any relatives. Money was sent back for months to her family to help them rebuild a life in Avdimou.

“I had an all-right time in Italy, learning the language quickly, and slowly starting to make friends,” she says, reminiscing on the ten years she spent there.

Eventually she followed her sisters to America who had also left in the years that followed, adopting the country as her new homeland. The years away were hard, working and taking care of her sisters’ children in another world.

She eventually married and had a daughter, but she always says, “I don’t forget the road I took to get here.”

She missed Akanthou and Cyprus, feeling ripped out of having a life in her own homeland due to the war that tore them away.

Maria soon followed Katerina but went to the US immediately. She left Cyprus in 1978, taking a job as a maid in New York.

She was not well treated by her employers. They kept her salary from her, and in the end never paid her for two years of work.

“I remember being sad that I couldn’t send money to my family,” she says, but her parents assured her that they were doing fine.

Maria also married and had two sons, but became a widow shortly after, losing her husband five years into her marriage.

“I struggled, having to learn English, learn how to manage my husband’s business and raise my children,” she says.

Maria brought Christina to America in 1985, needing help to raise her family and run her business.

“I never wanted to leave Cyprus,” Christina says, who always longed for her country in her heart.

“But my sister needed me.”

Christina spoke a little English, took some courses, and eventually also started working at Maria’s ice cream store, Carvel.

Christina eventually married in the US and had me and my sister.

I clearly remember the first time I heard the story of the invasion that forced the family to separate. I was seven.

My mum described her trauma one night in the car after a church festival in New York, where there was a fireworks show.

During the show my mum disappeared into the building, nowhere to be found. On the car ride home, I asked what happened, and she explained how the loud bangs always reminded her of the bombs she had fled.

The story unfolded and the longing for her wish to return crept into me, the longing for a home sealed behind barbed wires in a land that at the time was a mystery to me.

It all made sense now, even the heavy weeping of my grandparents every time we would visit Cyprus and leave.

“It was the pain of missing us and knowing we were going to foreign lands again,” my aunt Katerina explains. Their parents were happy that their daughters – sent away in their youth to build new lives abroad – had made it, but leaving always felt tough.

When they left Cyprus, the three women had no support from the government, their family had little money, and the country pushed them to foreign shores in a strange land.

Fifty years on, their lives in Akanthou are a poignant memory, which the war took away from them.

Click here to change your cookie preferences