There are better ways to call out successful men

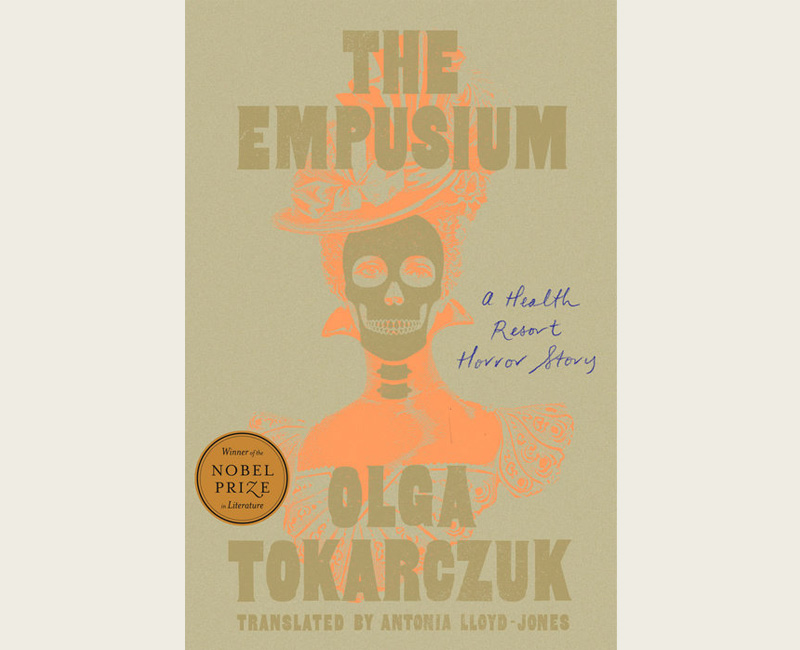

As so often, I am late to the party on this one; The Empusium is my first Tokarczuk read. The party I anticipated was a big one: a novel by a Nobel laureate, published hot on the heels of The Books of Jacob – a universally acclaimed masterpiece whose vast length made it tragically unfeasible on my reviewer’s reading schedule – and bearing the tantalising subtitle, A Health Resort Horror Story. Sadly, as so often, I timed my entry to an author poorly; The Empusium does not live up to its billing.

We get off to a good start: a disorienting disembodied first-person plural narration introduces the novel’s protagonist, Mieczysław Wojnicz, a young Pole arriving at the famous Görbersdorf sanatorium to cure his tuberculosis. We have an isolated, apparently idyllic, setting where death is always in the air, but where the air itself is meant to cure the dying. We have a cast of eccentric male characters, from the young homosexual landscape painter who befriends Mieczysław, to the pederastic academic who attempts a bungled seduction of the same, to the innkeeper that takes his residents on much-vaunted dining excursions where they are unwittingly fed fish tape-worms caught ‘in a sort of ritual of fervent exchange of sperm’ and the hearts of rabbits dead of heart-attacks, to the undercover policeman who hints that our protagonist has cause to fear for his life. Why? Because in Görbersdorf, at least one young man dies in brutal fashion each year, always in November. Creepiest of all are the Tuntschi, sex dolls crafted out of moss and sticks and leaves that one can find dotted about the forest where they are left by the charcoal-burners who use them for sexual relief. Needless to say, where there are creepy dolls in a horror story, you can be sure there’s more to them than that.

Christmas is coming, and tension builds as we wait to see whether Mieczysław’s aim of getting home by the end of the year will come to pass.

The problem is that the story is subordinate to Tokarczuk’s message that misogyny is harmful, ludicrous and historically enshrined. It’s an important message, but she chooses to deliver it by having her male characters engage in interminable discussions during which we hear about the ‘intellectual void’ of the female and the necessary benefits of marital rape, among other nuggets of wisdom. At the end, Tokarczuk places a note in which she lists the eminent men from whom every misogynistic comment in the novel is derived, from Augustine to Freud to Kerouac. It feels like the note is meant to come as a revelation. It doesn’t. Most of us know that famous men have been peddling sexist awfulness for as long as we have been making men famous. They deserve to be called out, but there are better ways than wasting a decent novel on it.

Click here to change your cookie preferences