Yoav Gallant knew he was living on borrowed time as Israel’s Defence Minister after Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s first attempt to sack him last year failed in the face of some of the biggest protests ever seen in Israel.

Netanyahu backed down that time, but relations between the two have never recovered and they wrangled constantly as the war in Gaza has ground on into its second year.

There have been regular rumours that he was on the way out but he refused to go, remaining a thorn in Netanyahu’s side as he argued for a hostage deal in Gaza and clashed with other parties in the coalition over drafting members of the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community into the military.

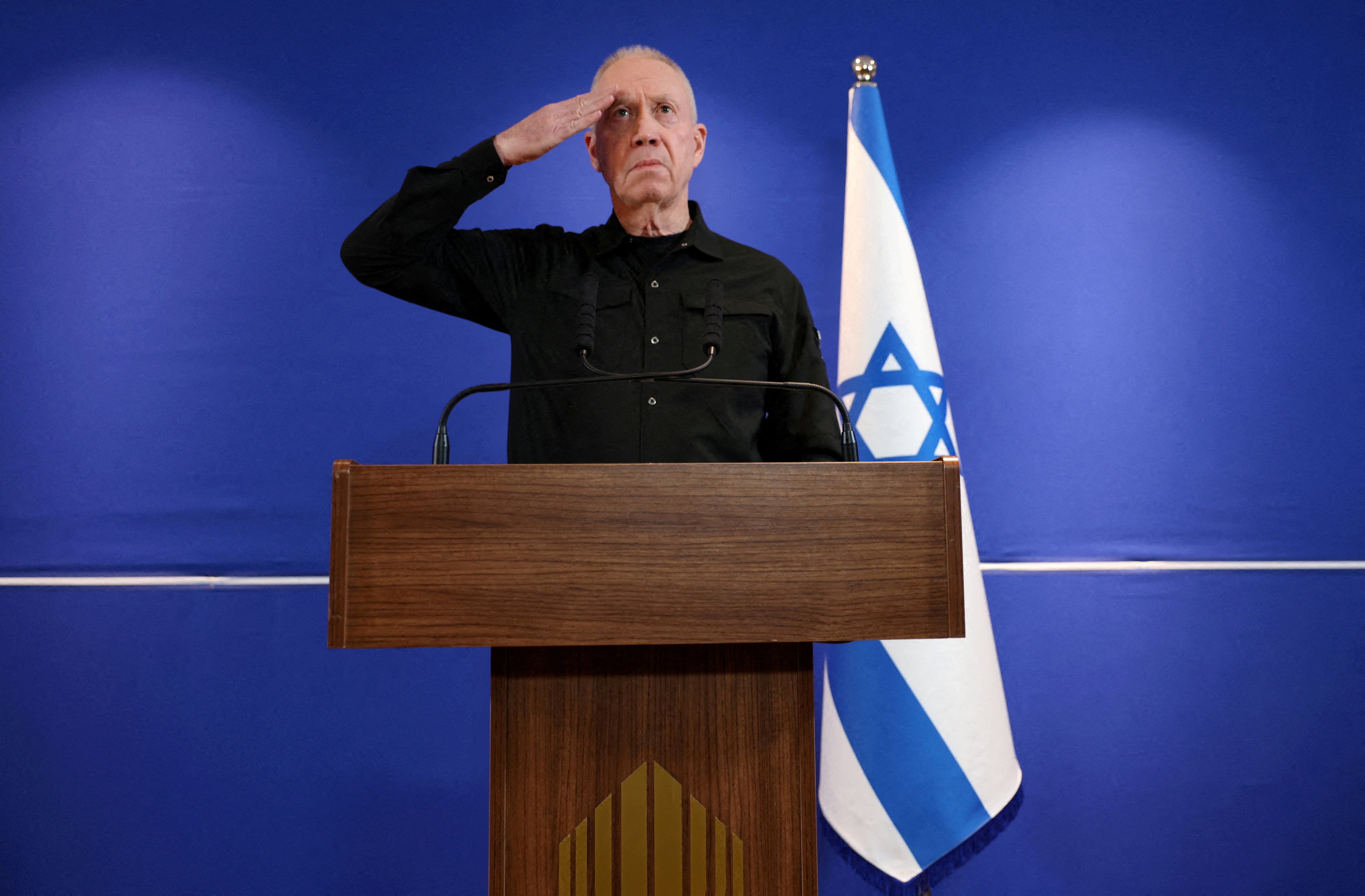

In a televised statement after he was sacked on Tuesday, he said Israel was navigating through the fog of battle and “moral darkness”, calling for a return of the hostages, a draft law for the ultra-Orthodox and a commission of inquiry into the failures of Oct. 7, 2023. He ended the statement with a military salute.

Like the prime minister, Gallant’s career was scarred by the events of Oct. 7, when Hamas-led gunmen killed about 1,200 Israelis and foreigners, and seized more than 250 hostages in an attack on communities around Gaza.

He has said that both he and Netanyahu should be investigated, touching on widespread criticism of the prime minister in Israel for not accepting responsibility for one of the biggest disasters in the country’s history.

He has clashed repeatedly with the hardline pro-settler parties led by Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, who was one of the first to congratulate Netanyahu for sacking him.

Just as hawkish as Netanyahu when it came to fighting Hamas and hunting down its late leader Yahya Sinwar, Gallant declared at the start of the war that the price Gaza would pay “will change reality for generations”. He described Israel’s enemies as “human animals” and said Israel was imposing a total blockade on Gaza, with a ban on food and fuel imports.

As the war has gone on, however, he has appeared more ready to end the fighting than Netanyahu, engaging more visibly with the families of the hostages still held in the enclave, and arguing weeks ago that the time had come for a deal to bring them home.

He has dismissed Netanyahu’s insistence of total victory over Hamas as “nonsense” and repeatedly urged him to produce a plan for running Gaza after the war. At the same time, he has rejected any suggestion the Israeli army could stay as an occupying power, to the anger of those like Ben-Gvir and Smotrich who have said they would like to resettle Gaza.

But both he and Netanyahu face the threat of an international arrest warrant over the campaign in Gaza – which has destroyed the enclave and killed more than 43,000 Palestinians – following a request from the International Criminal Court’s prosecutor in May.

That possibility has caused outrage in Israel but the issue of responsibility for the military and security failures that allowed the Oct. 7 attack to happen has been behind much of the tension in Israeli politics since then.

LIFE’S MISSION

After a 35-year career in the military that began in a naval commando unit, Gallant rose to the rank of general before going into politics a decade ago and becoming defence minister when Netanyahu returned to power at the end of 2022.

Highly regarded by the U.S. administration and other foreign allies of Israel, he never appeared relaxed in the world of party intrigue, appearing more comfortable talking to soldiers in the front line, dressed in one of the black uniform-like shirts he adopted at the start of the war.

“The security of the state of Israel was, and will always remain, my life’s mission,” he said in his first statement after the news of his dismissal.

With Israel now engaged in a multi-front war – in Gaza, with the Iranian-backed Hezbollah movement in Lebanon, and potentially with Iran itself – the timing of the dismissal has faced heavy criticism.

Gayil Talshir, a specialist in Israeli politics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, said that after the disputes with Netanyahu and the recent tensions over the conscription law, it was clear Gallant would be sacked at some point.

“It was just a question of timing. And the timing, on the eve of another possible attack by Iran, is the worst you could have expected,” she said.

The tensions with Netanyahu go back to at least the middle of last year, when Israel was split over a drive by Netanyahu to curb the powers of the Supreme Court, with huge weekly protests against a move critics saw as an assault on democracy.

As the protests mounted, Gallant broke ranks and spoke out against the plan, which he said was causing such deep social divisions that it endangered national security.

That prompted Netanyahu’s first attempt to dismiss him, a move he abandoned after hundreds of thousands of Israelis took to the streets in a spontaneous wave of protests that shut down the country.

Click here to change your cookie preferences