A Cyprus teen makes a notoriously hard skill look easy. The result of his endeavours will go on show in Limassol later this month

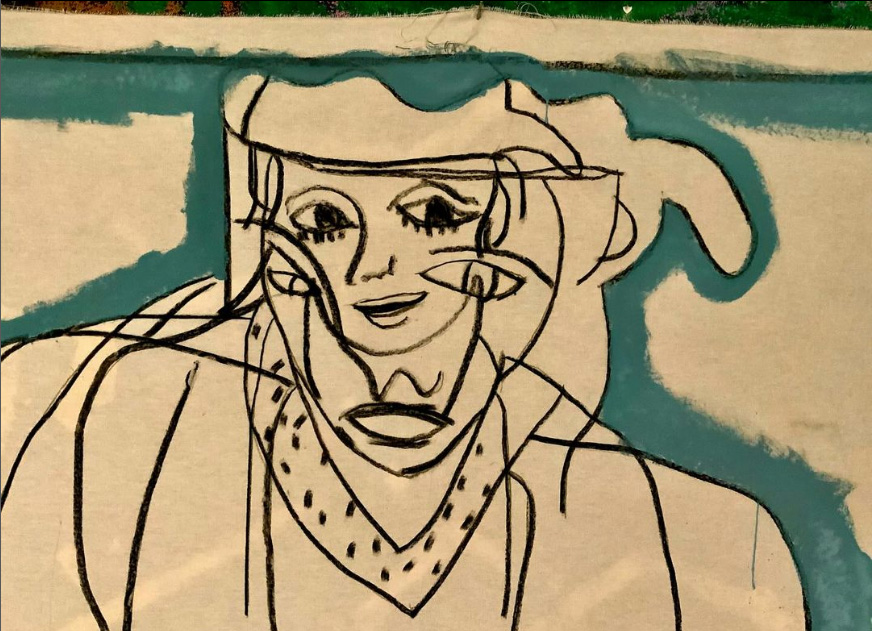

The little boy doesn’t hesitate once. He’s only 10 years old – the video was shot in Kakopetria in 2015 – but the piece of charcoal flies across the paper, adding lines at lightning speed: straight lines at right angles, then diagonals, then a frilly fringe. A stray trapezoid forms into a face, the lines collect into a vaguely equine shape. At the end he finally pauses – and an adult hand comes into the frame, prompting him to sign his name: ‘PARIS’.

The short video is on Paris Sergiou’s Instagram page, @parissergiou2004 – and 2004 is indeed when he was born (on June 5, to be precise), meaning he’s barely out of his teens. Put him in front of a canvas, though, and that same unstoppable flow still emerges, pouring out of him like water from a spigot.

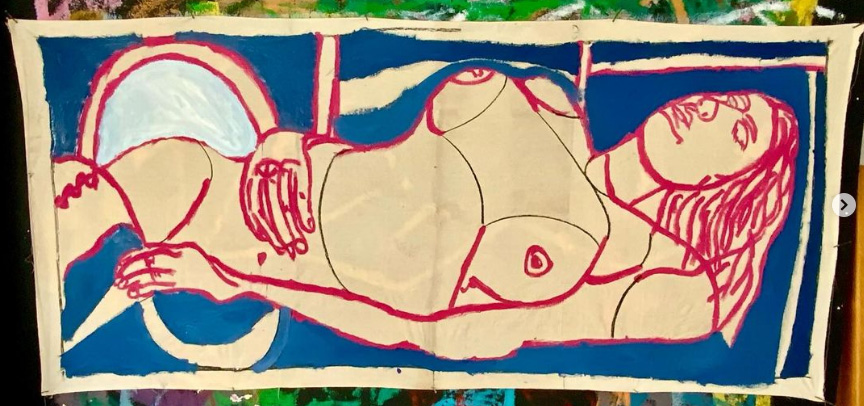

His studio in Nicosia, taking up an entire floor of an old block of flats, teems with artworks – but it’s not just their number, it’s also that most of them were accomplished in a single sitting. This one took half an hour, says Paris, pointing to a charcoal-only piece on a two-metre canvas. “The ones with colours can also take half [an hour], or one hour tops.”

Admittedly, there’s no special skill in working fast if the results are mediocre – but Paris’ growing reputation testifies to quality as well as quantity. He’s represented here by Diatopos Centre of Contemporary Art – who hosted his exhibition Preconscious last February – and also has representation in Madrid (Monat Gallery), Austria and Greece. A big show at El Greco in Limassol starts on November 23 – then later, in 2025, comes an exhibition at Artifact Gallery in New York, which apparently discovered him on Instagram, and offered him the 2025 slot, a full four years ago.

How often does he paint? “Almost every day, whenever Dad can make it.” ‘Dad’ is Charalambos Sergiou, whose role in this context is to drive his son to the studio – and indeed the urge can strike at any hour. They’ll sometimes rush over at three in the morning so Paris can get the creative itch out of his system, says Charalambos, the four of us (the fourth being his wife Vaso) sitting in a circle in the studio.

“When I can’t sleep at night, and this one” – indicating his dad – “is still up and working, I ask him,” explains Paris lightly.

And then he comes to the studio, sits at the canvas and knows exactly what to do?

“Yeah.”

How does he know?

“I just know.”

“You feel it in your soul?” prompts his father.

“Yeah.”

“When it comes to art, he’s a little soldier,” says Vaso earlier, speaking of her son’s prolific output.

“When it comes to art, I’m a prodigy,” adds Paris without a trace of arrogance. He’s not being vain, and not exactly being funny either (though he has a good sense of humour, and a booming laugh to go with it). He’s just stating a fact.

He’s an unusual person, not just a talent but a singular talent. Any viewer – even those without a deep knowledge of art – can see that he’s special, able to access his creative flow without inhibitions. A neurologist might say that he’s on the spectrum. For his parents, however, he’s the young boy (the younger of two) who first started drawing at the age of three – and they instantly noted that his lines were correct, the proportions were true. “We understood that whatever this baby did turned out right, artistically speaking.”

Charalambos and Vaso are – or were – artists themselves, which helped. (Their most recent project was an unconventional group exhibition in 2014 where the artworks were exchanged rather than sold.) But what made them progressive was above all their parenting philosophy, their firm belief that the first five years are “what determine where a child will end up” – and especially their refusal to apply the usual filters, to try and ‘guide’ Paris’ creativity, to make him draw little suns and houses like other children. “We just left him free,” explains Charalambos, “without repressing him.”

What was he like as a child?

“He was hyperactive,” laughs Vaso. “He couldn’t sit still for a second. He was not an easy little boy. But when he was painting he wasn’t hungry, wouldn’t whine or complain, nothing. When he’d paint, it was like he entered another world.”

“I’m still like that,” puts in Paris. “When I paint I don’t eat, don’t drink, nothing!”

And how does he feel when he’s painting?

“Free.”

Freedom is a big deal in Paris Sergiou’s worldview. His art is free, that unstoppable flow of the boy in the video. “Paris doesn’t erase,” explains Vaso. “Everything you see here,” she gestures around at the studio, “is stuff where he’ll come in, make [the art] and never have a second thought, like ‘Oh, that’s no good’. Maybe sometimes he’ll add something later – but he’s never erased a line in his life. Ever since he was a baby.”

Anyone who’s tried to make art knows the corrosive power of doubt, the urge to revise, the anxious tendency to second-guess oneself; Paris doesn’t second-guess himself. He does something notoriously hard, and makes it look simple. The vision seems to come at him whole, fully-formed, his only job being to pour it out on canvas. The title of his recent exhibition – Preconscious – seems apropos, I point out, and his parents agree.

“I believe that Paris, in the moment when he’s creating, lives in an intermediate space between the conscious and the subconscious,” offers Charalambos. “It’s a space that people – the rest of us, I mean – just kind of pass through. But Paris is able to stay there, taking from both sides.”

Freedom is important in another way too: in his outlook, his general temperament. The artist’s work is inevitably solitary – the silent, self-sufficient ‘other world’ described by his mum – and Paris isn’t always very verbal, letting his parents do much of the talking. Yet his energy is sociable and he is, in his way, quite an extrovert.

He loves travel, and the buzz of new places. He’s taken part in two artists’ residencies (accompanied by one or both parents), a month in India and two weeks in Spain, plus a live exhibition in Salzburg. He loves going on planes – he is after all an Air sign, a Gemini – and there’s also a more unusual aspect, a passion for making paper planes. It’s an intriguing choice of hobby: a craft, like his painting, something he can do with his hands – but also an exercise in flow and fluidity, a plane gliding gracefully through the air, like the airy flow of his own creative process.

He’s sensitive to noise (he’s sensitive in general), and I ask if he’d like to live somewhere in Nature – but he shakes his head. “Paris is a social animal,” observes his dad. He likes the urban hubbub and likes people, essentially. He loves to share – one of his joys as a kid was signing his paintings and giving them away to random strangers – and loves performing.

The event in Salzburg had him painting a piece every night, before an appreciative crowd. Another event, in Athens last May at the Takis Foundation, billed as ‘live painting’, had him creating a 5×3-metre artwork “in real time”. Paris was presented with an empty canvas and a ladder (his parents had the job of moving the ladder around) and produced “the energetic portrait of the place,” as he describes it, in about three hours. The response was overwhelming, including not just fan mail but also artworks painted by kids in the audience who’d been inspired by watching him.

What he does is indeed quite inspiring: he makes art organically, plunging in without fear or self-consciousness. As already mentioned, he does something hard and makes it look simple. Still, making art is one thing, living in the system quite another – especially a system so unsuited to someone as guileless and unfiltered as himself.

Paris left school at 15, to be homeschooled and concentrate on art. “He was unhappy,” explains his father. “He had to leave.” (Their older son Adonis, who’s a filmmaker, also dropped out of school to pursue more creative endeavours.) “I knew I wanted nothing to do with school on my first day of preschool,” notes Paris wryly. “I only put up with it all those years because I didn’t have a choice.” He starts to say more – there’s mention of bullying – but his parents gently bring an end to the topic, as if unwilling to open old wounds.

“I think Paris is like a paralysed person who goes in the water and feels instantly liberated,” muses Charalambos later, speaking of the effect that painting has on his son. “Outside the water there’s all that frustration, that immobility – and then in the water, there’s a liberation.” It’s a lovely metaphor, yet there’s also an edge to the words. Easy to talk of freedom here, with Paris in his studio, surrounded by his art – but most of life takes place ‘outside the water’, so to speak.

Paris keeps going, nurtured by his talent – his flow – and the love of his close-knit family. He’s growing all the time (he’s only 20), and becoming more adept with other people; even his art now incorporates the human form, after a period of being mostly abstract. The upcoming show in Limassol is especially interesting – because El Greco isn’t a gallery, it’s a furniture showroom, a vast space whose walls will allow him to exhibit some of his larger pieces, too large for conventional venues.

And what of the future? What if the unstoppable flow does someday stop? What if he sits before a canvas and finds himself suddenly beset by the same doubts and demons that haunt other artists? “I’m not sure,” he replies slowly. “But this – all this here” – he adds, indicating our surroundings, “I don’t know if it will reach a higher level. It might just stay the way it is”.

It’s an honest response – and perhaps that’s the point, that Paris makes art honestly. He paints because he wants to, because he has to – for fun, for therapy, to steady the hyperactive flow in his head. If he didn’t feel that burning need to do it, he wouldn’t do it; thus, for instance, with the paper planes.

He made them for years, he tells me, literally thousands of planes, trying to make “a series of the best 15 or 20 paper planes”. In the end, he explains, he succeeded; he constructed the best possible paper planes – the fastest, the best at flying – so “now I’ve stopped”. He’s not going to make any more. “This work is never going to end,” he affirms, meaning the art. “But the other one had to end.”

Art needs a first line and a last line: a starting point, a vision of what you’re doing, and an end point, a sense of when it’s complete. Often, the problem is how to begin, but he just plunges in without hesitation. Other times, it’s knowing how to end – but that too comes naturally. That’s why he never has to erase anything – because, says Paris, “I understand when I’ve reached the last line that has to go in”.

The paper planes reached their ‘last line’. Maybe the painting will too, and he’ll move on to something else. Meanwhile, he’s an artist with a very particular flow – a preconscious artist who can sense the whole vision, feel it ‘in his soul’, then simply do it. “That’s one reason why I’m unstoppable,” he muses – again, with no trace of arrogance. “Because I know where to start, and I know where to stop”. Simple.

Click here to change your cookie preferences