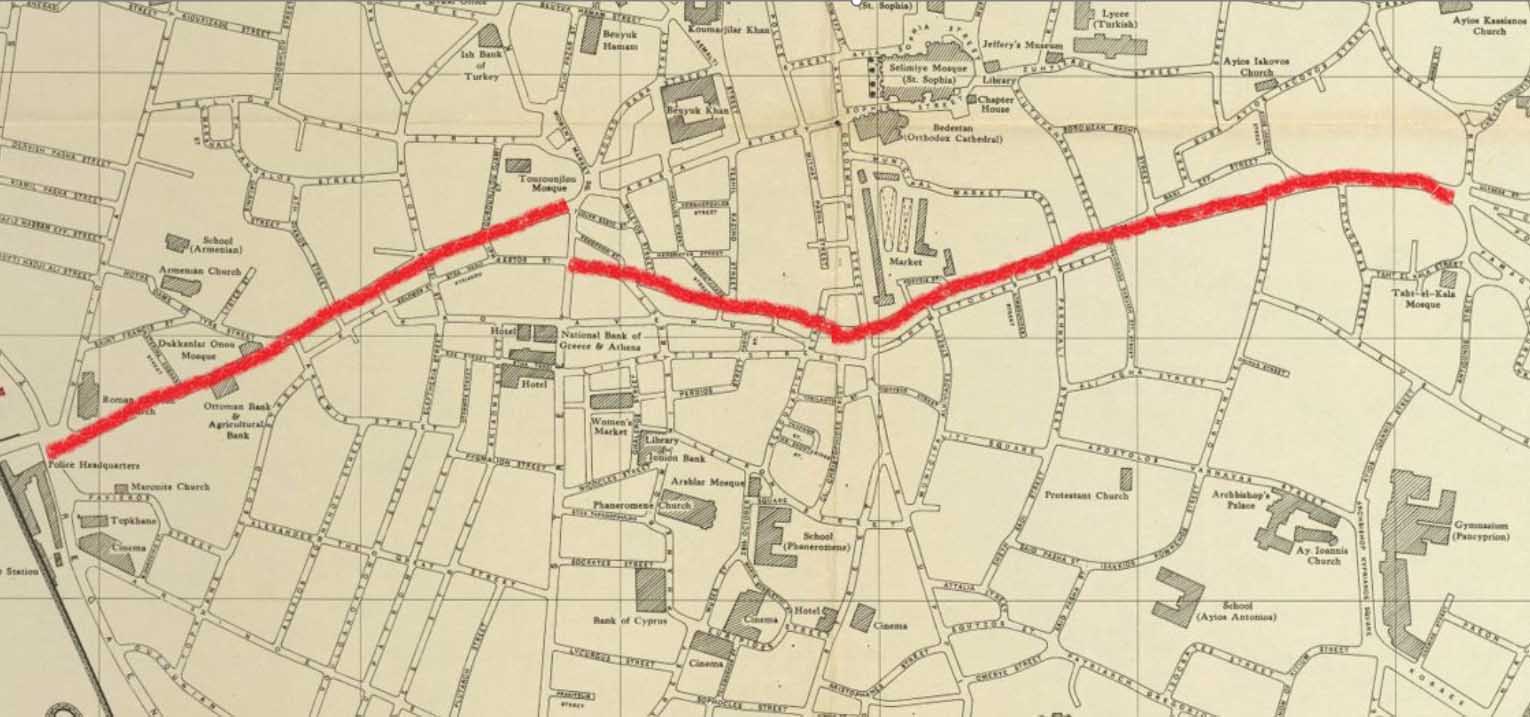

Nicosia’s Green Line has existed since 1963, but until the Turkish invasion it was not quite the impassable barrier it would become

A photo, taken in the Turkish Cypriot enclave of northern Nicosia in the late 1960s, shows 15-year-old Suleyman posing with his rifle and his best friend, the two lads having heeded the call to perform sentry duty on the newly established Green Line: schoolboys by day, soldiers by night, as he puts it.

The task of defending the enclave was a paid job, even for boys. “With the first salary he got as a fighter, which was five Pounds,” says Dr Maria Christodoulou, “he went down to Ledra Street” – on the Greek Cypriot ‘side’, though the sides were less established than they are now – “and bought a suit, which he’d had his eye on for some time”.

The photo of young Suleyman was part of a lecture (followed by a Q&A session) given by Dr Christodoulou at the University of Cyprus last week, organised by the Department of Turkish and Middle Eastern Studies and entitled ‘Everyday Life During Partition: Nicosia Within the Walls, 1964-1968’.

Christodoulou, an independent researcher making use of archive materials, secondary sources and interviews with both sides, paints a vivid picture of a segregated city during an era marked by denial, both at the time and (even more) now.

In fact, as she noted during the Q&A, one gets the sense that “the Turkish Cypriots grew up in this way” – that’s to say, with a constant fear of the other side – “while the Greek Cypriots live with a kind of national amnesia, [believing] that nothing happened before 1974”. No wonder the Cyprus problem is so intractable.

The Turkish Cypriots weren’t forced into enclaves by the Republic, of course. The impetus came from their own leadership, whether for security (after the intercommunal troubles of 1963) or to encourage partition.

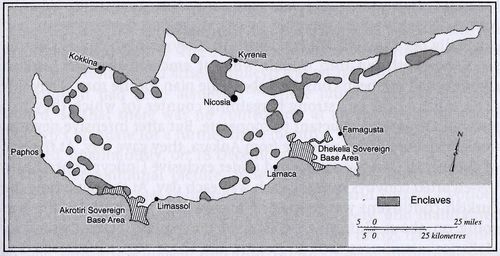

Several dozen enclaves were created in response to the troubles, based in neighbourhoods or villages that were already Turkish Cypriot but also forcing many to abandon their homes and move there. The Nicosia enclave was the most prominent, stretching from the northern half of the walled city all the way up to Kyrenia, though the Green Line (drawn by the British as a ceasefire line in 1963) wasn’t the hard physical barrier it became after the invasion.

Officially – even though around 500 Turkish Cypriots continued to be employed in the public sector, and several hundred crossed the checkpoint at Famagusta Gate every day – the enclaves were sealed off, with fines and prison sentences for Turkish Cypriots caught fraternising with the other side.

Everyday life, however, “had almost nothing to do with official state policy”.

Thus, for instance, the story of Suleyman, a boy who took up arms “to defend the vision of the Turkish Cypriot community, let’s say. Yet, when it came to the very first salary he received for that purpose, he went and handed it over to the Greek Cypriots!”.

Segregation was a relatively new thing; Christodoulou dates the rift between the two communities to 1956, when Turkish Cypriot special policemen were killed by Eoka and the British (who, of course, stoked the conflict for their own reasons) put up barbed wire “to separate Greek and Turkish Cypriot positions” for the first time.

Given how recent the rupture was, the years of the enclaves were a kind of transitional time, when the people of Nicosia hung on precariously to the city they’d known even as it began to change beyond recognition.

Merchants continued to trade across the Green Line. Bakers and yogurt sellers continued to ply their wares. One of Christodoulou’s interviewees recalls her family continuing to pay rent to the Greek Cypriot owner of their small shoe factory within the enclave, paying the cash through Armenian intermediaries. Teenage sentries from the two sides would often end up chatting and helping each other with homework, balling up paper and chucking it across the divide.

At the same time, however, the two sides were being pulled violently apart, living two quite different realities.

Many Turkish Cypriots, having been forcibly relocated, lived as refugees, sheltering in tents, stables, mosques or empty school halls. The enclaves had also been placed under embargo by the Republic, which declared them illegal.

Food shortages were endemic and often severe, alleviated only by twice-weekly shipments of aid from Turkey and the Red Crescent; “These shipments, however, were essentially at the mercy of the Greek Cypriots, who controlled the roads”. It’s no secret – and was mentioned by an audience member at the lecture – that Makarios’ policy was to make life as hard as possible for the Turkish Cypriots, even to the point of starvation, so they’d abandon their bubbles and rejoin the Republic.

Life in the enclaves was heavily militarised, not to say propagandised. For the first time, a generation of Turkish Cypriots grew up unable to speak Greek – the language of the majority who, they were told, wanted their destruction. Meanwhile, across the Green Line, the Greek Cypriots were going through their own, more subtle form of alienation.

On the surface, life went on as before. After all, says Christodoulou, “the Greek Cypriots had the Republic, with all its money” – all the international funds which the new state had been granted to establish itself. “If you threw sand up in the air, it wouldn’t fall on the ground,” recalls Christakis, a metal-worker in old Nicosia, to illustrate how busy the streets were.

In 1968 – the year when the embargo was finally lifted – “the biggest political fuss”, says Christodoulou, quoting her interviewees, “had to do with a British starlet who’d posed with Archbishop Makarios while wearing a mini-skirt”. Cinemas and nightclubs were packed. At one point, a stir was caused when “the bouzouki player at the famous Antonakis bar complained about customers not wearing ties”, which he felt lowered the tone of the place.

Yet the atmosphere was fraught, rife with undercurrents – not just a constant background trickle of murders and kidnappings but “a plethora of dim and confused images”, as Christodoulou put it in her lecture. “Newspaper sellers in a city full of barbed wire announcing the latest horrifying news from the other side… Excited schoolkids singing songs for the motherlands at national holidays, boys with guns everywhere, groups of suspicious men sitting in taverns and coffee shops relaying the latest conspiracy theories…”

In short, the years of the enclaves presaged the situation that came later, and became calcified after the invasion. On the Turkish Cypriot side, a turn towards isolation and militarisation. On the Greek Cypriot side, the “national amnesia” and denial of reality that persists to this day.

It’s all very sad – but what if it’s also a survival mechanism? Christodoulou opened her lecture by citing sociologist Fran Tonkiss, who believes that “urban peace… is based, to a large degree, on indifference and apathy”, a detachment that allows co-existence between capital-O ‘Others’ in urban society.

Society, admittedly, is divided now – yet denial may still play a role. Talk of the enclaves was avoided at the time by Greek Cypriots (who took refuge in busy streets and British starlets) and continues to be avoided now, a semi-conscious apathy that serves to keep the peace, so to speak. Alas, it also ensures that the gap between the two sides remains.

Click here to change your cookie preferences