Upcoming TV may well be better than source novel

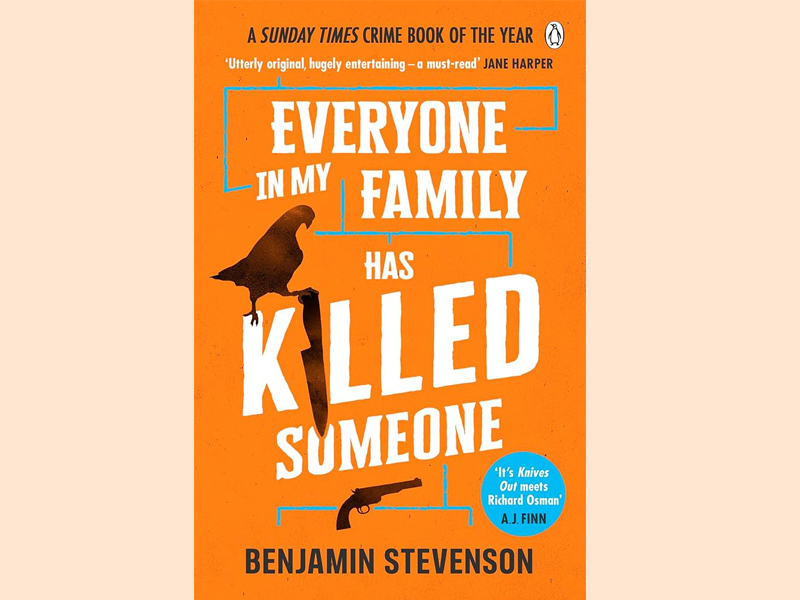

Last year, I read The English Experience by Julie Schumacher, in the course of which I discovered the existence of The Thurber Prize for American Humor – which she had won in 2015 for a previous novel with the same protagonist. Having been in the midst of a few reading months where all my usual resources for helping me decide what to read, including the Booker long/shortlists, were offering up nothing but grave literary fiction, I decided to explore the nominees for this year’s Thurber. One promising contender was Everyone In My Family Has Killed Someone by stand-up comedian and crime writer Benjamin Stevenson. Rather sadly, however, it appears that the Thurber committee, whoever they might be, are getting rather lax with their criteria, since this novel is not very funny. And Australian.

The idea here is that it’s a crime novel delivered from the perspective of a narrator who writes how-to-guides for people who want to learn how to write crime novels, and who outlines all the rules by which he will construct the story, as well as many of the critical events, and the fact that he will be an utterly reliable narrator, in the very first pages.

Our narrator is Ernest Cunningham, of a family upon whose astonishing infamy he insists over and over again. The Cunninghams are called to assemble at a ski resort in The Snowy Mountains for a particularly special family reunion: Michael, Ernest’s elder brother, is about to be released from a jail term for murder, which he had to serve because of Ernest’s testimony against him. That’s right; there’s more than a little familial tension. Needless to say, the bodies start piling up relatively quickly, though the fact that the new victims bear the hallmark of a serial killer whose modus operandi is an ancient Persian torture technique, starts to raise some unsettling questions about what Ernest means when he says, ‘Everyone in my family has killed someone. Some of us, the high achievers, have killed more than once.’

It’s neither a terrible idea nor a terrible book. The problem is that for a novel this metatextual to work, it needs to be so compelling as to render the incessant self-referencing a cute or witty quirk. It’s not nearly compelling enough. The characters are on the blander side of generic; the phrasing is solid, not stylish; and the plotting is not fast enough to cover up the plot holes, of which there are more than the one that Ernest promises. On the other hand, it has been snapped up by HBO and I will be watching when it comes out, because this is a novel where a TV adaptation promises to be better than the original.

Click here to change your cookie preferences