By Loukis Skaliotis

There is growing realisation in Europe that relying on itself for its defense is a top priority. President Trump’s “America first” policies have not taken long to drive home the point that Nato cannot be the bedrock of security in Europe that it once was. Hearing Trump say that there is a beautiful ocean between Russia and America can only have been music to Putins’s ears.

Last week, we witnessed for the first time, the US voting against a UN General Assembly resolution supported by almost all European counties on Ukraine. Even though the resolution passed, despite the US sponsoring another resolution that did not refer to Russian aggression in Ukraine, this was of little comfort as in the Security Council the US, with the support of Russia and China, proceeded to approve the US version. The UK and France, once the partners of the US in these votes, could only abstain as they witnessed their once reliable ally forming a pact that would once be considered unthinkable.

The positive spin on this, that this represents part of Trump’s master plan to get Russia to agree to the deal he is preparing, cannot be relied on when the security of Europe is at stake. European leaders have therefore been scrambling to form a consensus, through a variety of partner meetings, on not only how to support Ukraine, but also on developing a strategy for boosting Europe’s own defence. President Macron’s hastily convened mini summit in Paris among the big players in Europe (including the UK), came after meetings between the EU, the UK and Norway.

Whereas any security arrangements for Europe will not happen overnight, finding a support mechanism for Ukraine is urgently needed. The US has targeted exploiting the mineral wealth in East Ukraine, (a lot of which is currently in land under occupation), as well as getting a cut on any reconstruction to be done after securing a peace deal. This was presented as either a payback for support already given, or in the more palatable version as a reward for future support. (See, US Treasury Secretary’s Scott Bessent’s article in the Financial Times on 22/2). While the initial proposal was considered extremely onerous, strenuous efforts were made to find a compromise solution.

Ukraine’s President Zelensky, has rightly asked for security guarantees as part of any deal. The UK and France committed to putting peacekeeping troops on the ground, guaranteeing the security of Ukraine in the event of a peace agreement, but both asked the US to provide a “backstop” to their commitment. Trump, while avoiding to commit to any guarantees by the US, indicated (on Macron’s visit to the White House earlier this week), that Russia was ready to accept peacekeeping troops from France and the UK, something that in the past it rejected. It was though unclear whether this was indeed so.

As it happens, it seems we will not find out. On Friday the whole effort fell apart. President Zelensky’s visit to the White House ended in acrimony, developing into a bitter exchange with President Trump and Vice President JD Vance. The visit was cut short with Trump warning Zelensky that if he was not willing to make the deal he would effectively lose his country. Zelenskyy now has only Europe to help him salvage the pieces. Today (Sunday), he is meeting in London a number of European leaders and what happens is anyone’s guess.

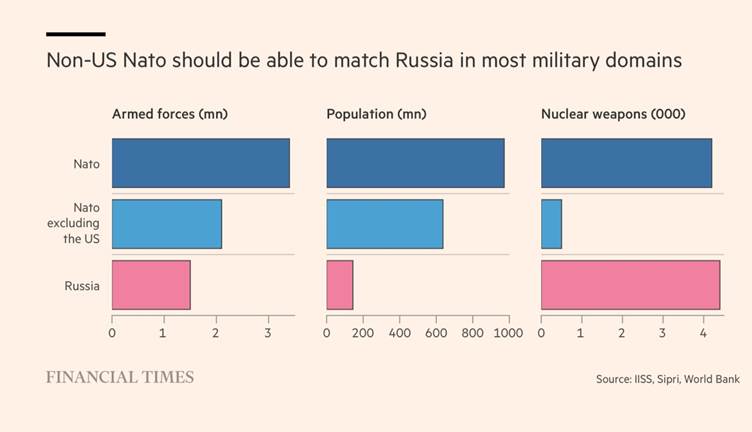

What is beyond doubt, is that events have brought to the fore the need for Europe to strengthen its own security. For, notwithstanding what happens in Ukraine, the trust among allies that was fundamental in the Nato alliance has all but evaporated. At the risk of appearing to be blowing my own trumpet, I wrote in the Sunday Mail on January 12th that Europe needs its own nuclear deterrent. This has now become apparent with Macron’s insistence that European troops on the ground were not enough of a security guarantee to Ukraine. He emphasised that a US “backstop” was necessary. This, because Russia has repeatedly warned that any European troops on the territory of Ukraine (peacekeeping or otherwise) would force it to consider using tactical nuclear weapons. Tactical nuclear weapons, are smaller scale weapons that can’t specific military targets in the field of operations, as opposed to ballistic nuclear weapons which are aimed at whole cities.

The UK and France have between them 515 such ballistic missiles (source Financial Times, ‘How Europe can defend itself without US help’). They do not have any tactical nuclear weapons though. This capability is provided to Nato by the US. Hence, the need for the US backstop for a lasting peace in Ukraine.

Whether European nations can muster the political will to agree on developing a common defence will largely depend on the ability to finance any such plan. Contrary to intuitive sense, large defence expenditures do not necessarily imply a hit on economic growth. Particularly now that Europe is facing a weakening industrial base, not to mention the impact of any potential tariffs imposed by the US. To avoid, however, redirecting funds away from consumption towards the defence effort, something that electorates could be hard pushed to accept, increased borrowing at the European level must be made. I have already mentioned in my January 12th article that common European debt is perhaps the ideal vehicle to support this. Proceeding with using the frozen Russian funds held at Euroclear in Belgium as collateral for said debt would be a huge step forward.

For all that to happen, Germany following last Sunday’s elections, will play a pivotal role. Friedrich Merz, the leader of the Christian Democratic Union that won the election (the extreme rightwing Alternative for Germany AfD, came second with a sizeable 20 per cent of the popular vote, and was congratulated by Elon Musk), is a committed Atlanticist and has already said that Europe must become independent from the US. Germany has opposed increasing European debt and has avoided borrowing enough to boost its ailing economy and that of Europe. Part of the reason behind this is the so-called ‘debt brake’ that the Germans have incorporated in their constitution, preventing the government borrowing more than an arbitrarily set limit. Removing that ‘debt brake’ is something that Merz is in favour of, although a special two thirds majority in parliament is necessary to amend the constitution. Merz does not have such a majority in the new Bundestag, while the AfD, is strongly opposed to the change). However, the existing Bundestag which remains in place until the end of March could vote the change through. It is the kind of maverick political trick that Trump would have been proud of. Whether Merz can pull it off will be a sign of how the new German government can show the effectiveness necessary to lead Germany into a new era and help secure the defence of Europe.

A picture is a thousand words.

Loukis Skaliotis is an economist

Click here to change your cookie preferences