In the latest Hollywood star drawn to the island to take part in a film, THEO PANAYIDES meets the proverbial hardest working man in showbiz who credits yoga and walking up mountains with keeping him balanced

I’m due to meet Julian Sands at the St. Raphael in Limassol – and I do, but not in the way I envisaged. The hotel is shut; the entrance is blocked, the windows of the main vestibule papered over; signs admonish visitors to close the door behind them. The five-star hotel has been turned into a film set, the main location – and crew’s living quarters – for The Ghosts of Monday, the third production in three years by the Limassol-based Altadium Group whose previous film (S.O.S. Survive or Sacrifice) played local cinemas a couple of months ago.

My appointment is at 5pm, just in time for lunch break (the day’s shoot runs from midday to midnight) – but they’re running slightly late, as often happens on film sets, though in fact I’m assured more than once that this particular shoot is going incredibly quickly; I assume director Francesco Cinquemani (who previously made The Poison Rose with John Travolta and Morgan Freeman) is up against a hard deadline, since the hotel has to re-open and they’ll lose their location. I see him hunched over a monitor, a shaven-headed, black-clad Italian with an affable manner, and settle down to watch the crew setting up a long dialogue scene. “Antiseptic!” calls an assistant director – and a sofa is duly sprayed down, part of the Covid protocols that also explain the apples and bananas individually wrapped in cling-film in the ballroom that doubles as dining hall.

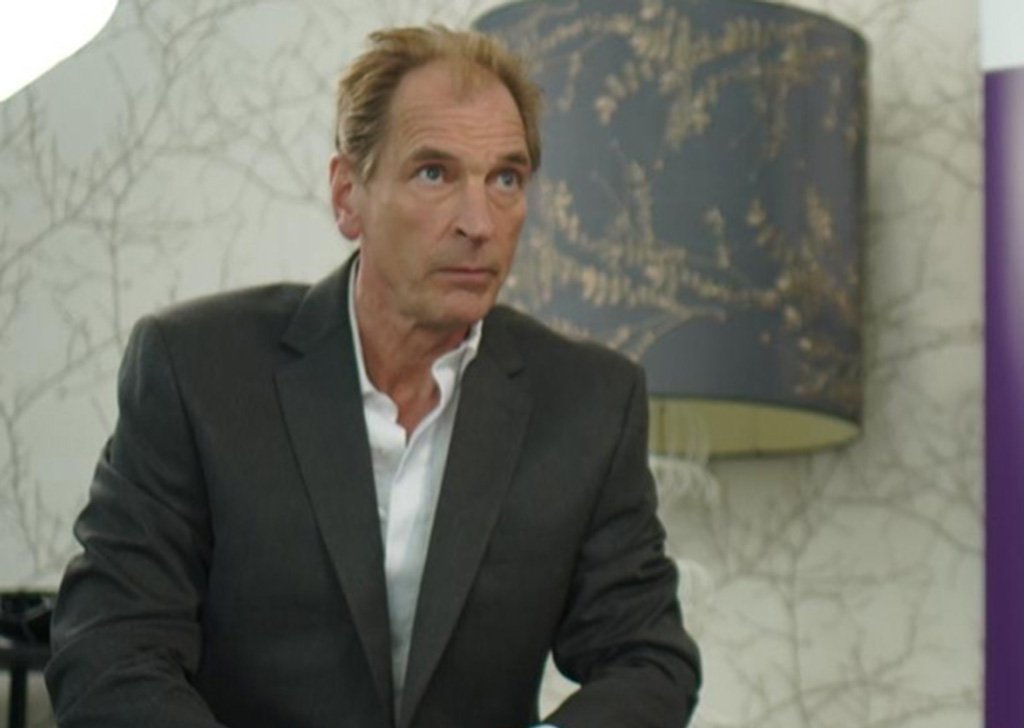

The cast and crew are from all over; I hear snatches of Italian, Russian, Greek (Cypriot accent) and English (British and American accents). The scene has four actors ranged around a living room, talking about the haunted hotel that’s the focus of the plot (shades of The Overlook in The Shining, though apparently there’s a twist; “The actors are not allowed to give away too much,” says producer Loris Curci, who also wrote the story). Julian Sands plays Bruce, a has-been actor now presenting a paranormal investigation show called Ghosts of the New World – but where is he, anyway? I look around and spot him at the back of the room, napping on a sofa in his cream suit while the crew get ready. It turns out they’ve been working on this scene since two o’clock.

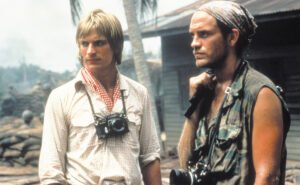

Julian is the star, of course, the main asset, the name whose presence guarantees distributor interest – and ‘presence’ is the operative word, since he’s one of those actors with a very distinctive quality. Even viewers who don’t know the name may recognise his gaunt, languid, slightly sinister manner from other films – especially since he’s made so many, having got his break with The Killing Fields in the early 80s. The persona works well with horror, and indeed his three most recent credits at the Internet Movie Database are The Ghosts of Monday, The Ghosts of Borley Rectory and Death Rider in the House of Vampires – but he’s also done children’s films, Oscar winners, period dramas, TV shows (Vladimir Bierko in 24, Jor-El in Smallville), obscure shorts, the voice of ‘Q’ in a series of James Bond radio plays. The Database lists 152 acting credits, and even that list is incomplete (not yet listed, for instance, is Benediction, a film about the poet Siegfried Sassoon which he made last year). He’s peripatetic, and the proverbial hardest-working man in show business.

“I was just in New Orleans,” he tells me later, “doing a television film with Phillip Noyce, when I was sent this script by Francesco – who I’d met in Rome, he came to see a theatre piece I did”. The Italian described the film as a homage to 70s masters Dario Argento and Ken Russell – and Julian was intrigued, since he’s actually worked with both Argento and Russell (and David Cronenberg, and Wim Wenders, and Mike Figgis, and Steven Soderbergh; the list goes on…). Next month he’s off to Hong Kong, then he’s working in Italy and Germany with up-and-coming filmmakers. He’s not undiscriminating, he assures me, indeed he’s quite picky when it comes to scripts, “but also, I like to work – so I’m open to young directors and producers, people who haven’t done much work, if what they say is intriguing.

“It doesn’t have to be a guaranteed commercial experience. I’m not interested in just being part of a product, like a ‘film factory’. I want something which is going to be an adventure.”

Boxing helena

A hearty, back-slapping type might revel in this freewheeling lifestyle, loving the enforced sociability of film sets (that’s why Covid protocols are relatively simple; you’re with the same few people day after day) – but Julian doesn’t seem to be that kind of person. I watch as the filming proceeds. He gets up when it’s time to do the scene, waits for ‘Action’, speaks the lines with a certain creepy brio that’s visible even at a distance – then stands a little apart after the director says ‘Cut’, arms folded, not really joining in the general chit-chat. Later he sits on the sofa with his legs crossed, chin cupped in hand like some pensive Victorian dandy.

“Going to a film set and watching the process, if you’re not part of it, is very tedious,” he admits. “You will be astonished by how much waiting there is. But if you’re part of it, you just sort of –” he snaps his fingers – “you come alive in a heightened way at the moments when you are working, and then you’re just in repose, in repose, and then…” He gestures to indicate coming alive again: “It’s kind of like a choreography”. Obviously, being on 152 film sets teaches a lot of life hacks – but it’s not just that, Julian’s whole energy seems honed, sculpted; he seems to have raised self-control to such a fine pitch that he’s able to be present but apart, unfazed, ‘in repose’ as he puts it. Note, for instance, that our interview is slightly delayed because he takes a 10-minute nap, to refresh himself after that tiring scene. How does that even work, is he able to just empty his mind and drop off?

“It’s kind of like a yoga shavasana,” he explains. “I do yoga, and that teaches me how to regulate my body.” Light on Yoga by BKS Iyengar was the book that changed his life, according to a recent Q&A in The Guardian; he read it 23 years ago, he adds in that piece – and the numbers add up, because he tells me he was “probably 40 years old before I became confident as an actor”. (He turned 63 last month.) Whether it was yoga or just growing up, it took two decades from the time he left drama school “to find myself as a mature person, as an adult”.

Sands at 63 is impressive, toggling between our interview and a parallel one with a Russian TV channel: his replies candid and unguarded, the blue eyes penetrating and alert, talking with his hands and a clipped, mellifluous accent that owes little to his native Yorkshire. He has something of the English aristocrat: his mother-in-law was Lady Caroline Blackwood, a “novelist and socialite” per Wikipedia, while he cites Lady Antonia Fraser as “my regular dinner date” (his eatery of choice is The Wolseley in London) in another recent piece in the Catholic Herald. But he doesn’t come across as staid or snooty – more like the upper-class adventurers of days gone by, those public-schoolboy sailors and explorers driven by restless curiosity and a thirst for all things “interesting”.

It’s not just the work that evinces his fearless streak – though it’s that too. His characters are dark, and often evil. He played a paedophile in last year’s The Painted Bird. He played a surgeon who cuts off his beloved’s arms and legs and keeps her in a box in Boxing Helena. I mention Naked Lunch, also from the early 90s, and he nods at the memory. “What I had to do was just so kinky,” he recalls, then shrugs: “You go with the flow”. His character was named Yves Cloquet, says Wikipedia, “a gay Swiss gentleman who appears to be a monstrous centipede in disguise”. Go with the flow, indeed.

in The Killing Fields

But it’s not just the work. He also climbs mountains, for instance – even now, at 63, not nice little hiking trails but proper mountains. “The last big mountain I climbed was in the Alps in September… A thing called the Schreckhorn, a real mountaineer’s mountain. Last year I’d gone to climb it and just below the summit, maybe 100m below, lightning came and we had to get down fast. So I went back this September, and was able to complete the climb.” He almost died on a climb in the 90s, after suffering a cerebral edema due to extreme dehydration on a peak in the Andes.

So what’s the attraction?

“There’s many attractions. The aloneness, the sense of silence.” Is that an attraction? “Yeah, it is; because you’re never [truly] alone. Because you are there. And your – inner light is a kind of torch, in the wilderness. Um, it’s fun,” he adds, on a lighter note. “It’s physically exciting. And it’s emotionally complex. Because climbing is very self-negating, but it’s also very self-affirming. The physical challenge isn’t as significant, perhaps, as the mental challenge of climbing a mountain.”

‘Self-negating’, ‘self-affirming’… The self, I suspect is central to Julian Sands’ worldview, even his acting (though of course he’s a very serious actor) serving mostly as experience, food for the voracious sense of self – self-awareness, a hunger for self-development – that’s probably what drove him to become an actor in the first place. Even having just met him, it’s clear that his energy is restless and complicated. I recall something else from that Q&A piece, a memory from childhood: “Aged nine, I was told I wasn’t invited to a birthday party as I was too loud”. What kind of nine-year-old gets shunned for being ‘too loud’? Unless of course it’s a euphemism for ‘totally impossible’.

One should make clear that he’s not some narcissistic monster. He has four brothers, and is close to all of them. He has three grown-up children, and “we text each other every day, we love each other, we’re very much in each other’s lives”. His centre of gravity is the Los Angeles home he shares with Evgenia, his wife of 30 years (there was also a brief first marriage in his 20s), where he reads, gardens, goes up into the mountains every day, does his yoga, makes use of his excellent wine cellar. Even here, however, when I ask about how he met his wife (they were introduced by the actor John Malkovich) and whether it was love at first sight, he turns a bit cryptic: “At that time – it was quite a complicated time for me, so there was certainly… You know, this expression coup de foudre, it suggests head-over-heels and great romance, but actually what it means is ‘very difficult time’. But listen,” he concludes with a grin, “we’re still together, 34 years later!”.

I hesitate, unsure what to ask about that ‘complicated time’ when he was younger and – presumably – less together. All this restless energy must’ve been hard to live with, I venture.

“Well, hard for me and hard for anybody who wanted to live with me, sure,” he replies with a grim chuckle. “I would say I’m more mellow now. More able to harness the energy, and focus it.”

Was he angry, back then?

“No… Well, who knows? I’m not an analyst. If I was, I had no particular consciousness of anger… Agitated, I think. A sort of anxiety, agitation.”

Sounds fairly typical, for an actor.

“Possibly.”

Yoga helped, as already mentioned. Mountain-climbing helps, allowing the self to blossom and recede simultaneously. Acting helps too, indeed it helps most of all – especially his kind of career, “being open,” as he says, “and being curious,” scouring the world for interesting roles and experiences. ‘Interesting’ is the word that recurs most often in our conversation. Darker roles tend to be more interesting than “straight” ones. Small independent films are always the most interesting. Spending three weeks in quarantine when he goes to Hong Kong next month – for someone who loves the outdoors, and likes to walk for miles every day – will surely be interesting, “as a meditation, as self-denial”. It’s all grist to his mill.

In the end, the films themselves are almost irrelevant; it’s striking that he doesn’t seem nostalgic, nor does he tell lengthy anecdotes about his past work. “Generally, I live in the present and the near future. The past is another country.” Living in the moment – a very yoga concept – informs every aspect of his life. Even as a film (not theatre) actor, performance “has to be about the playing of the moment, live,” he insists, somewhat counter-intuitively. (He knows there’s a camera involved, and that his performance will be edited later; he just doesn’t think about that.) Even on Covid, the issue du jour, he refuses to dwell on What Might Happen, the shadow of death that’s been cast over all our lives. “I’m not a Covid denier,” he says carefully, “but I’ve seen a lot of people who’ve become what I would call ‘Covid victims’ without contracting Covid… They’ve had their sense of being alive completely subdued, and a kind of catatonia has come over them.” He himself doesn’t seem the fearful type, I note honestly. “I think it’s important not to be,” he replies. “Especially if you’re going to be an actor.”

Really, though? An actor? Playing pretend in low-budget horror movies? Isn’t it something of a frivolous profession – especially for a serious-minded man like himself? Julian Sands frowns.

“I mean, it can be,” he admits. “And I can be as frivolous as the next person, trust me!” But there’s always something more, he points out, something for the actor to extract through nuance and detail – and his presence, that ineffable presence. “Now, this film for instance. It’s a haunted-hotel story – but what it’s really about is a family in crisis.” There’s “quite a profound” look at relationships, he opines about Ghosts of Monday – then we’re suddenly joined by an assistant quietly motioning him to the set, and he heads off to try and express that half-submerged nuance. Just another interesting day at the office.

Click here to change your cookie preferences