Dominic Cummings, the architect of Brexit, claimed on Twitter last week that cheating foreigners was the core part of his job as special adviser to the British prime minister during the Brexit negotiations, which was a mischievous and unpatriotic thing to say about Britain. Of course, cheating foreigners can also mean foreigners who cheat depending on the context, but Cummings did not intend a double entendre since he also said Britain did not negotiate the Northern Ireland Protocol in good faith.

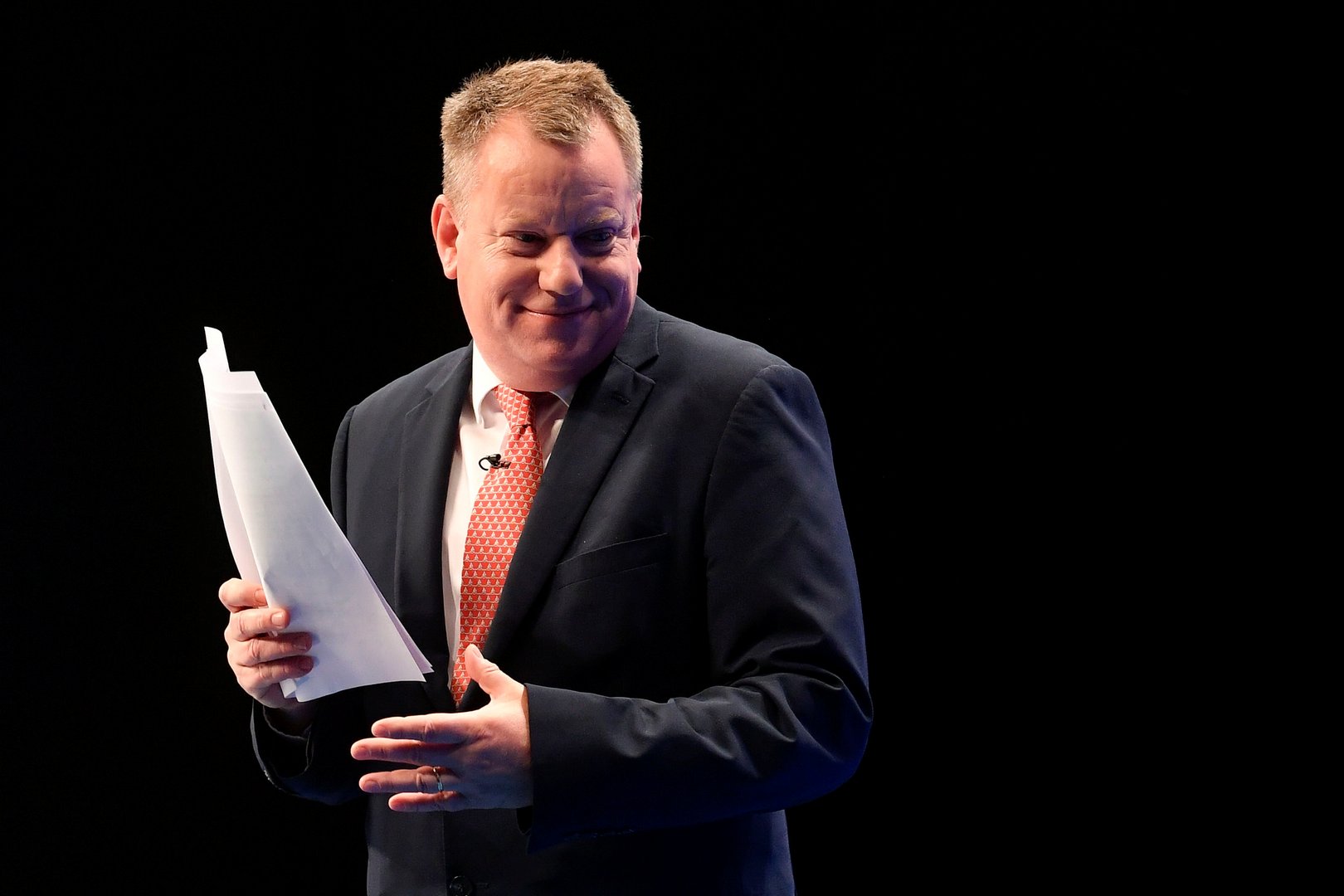

By contrast Lord Frost, the UK’s Brexit minister with a seat in the cabinet, insisted that Britain was acting in good faith in a speech he delivered in Lisbon on October 12, titled Observations on the Present State of the Nation.

The theme of his speech was inspired by the British-Irish philosopher statesman Edmund Burke who was a conservative traditionalist and whose dictum “politics should be adjusted not to human reasonings but to human nature… people must be governed in a manner agreeable to their temper and disposition,” Frost cited with approval twice in his speech in support of two fundamental propositions.

The first was that Brexit was an exercise in democracy not because the referendum was particularly democratic but because by exiting the EU the electorate took back control of government. His thesis was that in the EU many important things such as trade policy, monetary and fiscal policy and aspects of immigration control can’t be changed through elections, whereas with Brexit the British electorate took back control in a way that suits the British penchant of turfing out governments whose policies they don’t like.

The second proposition was that the UK government’s volte face on Northern Ireland is fully justified as the Northern Ireland Protocol is not working. He claimed that it is not unusual for a country to wish to renegotiate an international treaty soon after signing it.

As any student of the Cyprus problem knows, President Makarios wanted to do just that after Cyprus became independent within two years of signing the 1960 treaties. Lord Frost knows this from his time at the British High Commission in Nicosia in 1987, where he learnt Greek and mastered the Cyprus problem, though he must also know that reneging on treaty commitments so soon after signature landed Cyprus in a fine mess that remains unresolved to this day.

Lord Frost’s other arguments on Northern Ireland are more substantive. Contrary to Dominic Cummings’ cheating foreigners’ jibe, Lord Frost implied that the EU manipulated the problem in Northern Ireland to frustrate or dilute Brexit, which was unfair to Britain and unfair to the Protestant community – and ultimately bad for the Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement.

Lord Frost was at his most powerful, however, when he told the EU in no uncertain terms that the protocol did not create some sort of co-dominion between the EU and the UK over Northern Ireland. The protocol he said could not treat Northern Ireland as if it were a member-state of the EU and that Britain could not accept that an EU curtain has descended permanently across Britain on account of the protocol in its present form.

Last but not least he dismissed the Court of Justice of the EU as inappropriate to sit in judgment of disputes under the protocol since after Brexit it is not an independent and impartial tribunal. It is not impartial in terms of its composition but also because it is a political court whose paramount concern is the interests of the Union rather than justice between the parties in litigation before it.

The argument that Norway accepts the jurisdiction of the EU court is a bad argument for the simple reason that it compares apples and pears. Britain is not Norway and there is no Good Friday peace agreement to protect there – unlike Norway, Britain did not want to be part of the single market.

The damage to Britain’s reputation of reneging on the Irish Protocol within two years of its inception is containable. When a state consents to be bound by a treaty it must perform it in good faith. Consent to be bound by a treaty with no intention to comply with its terms is not good faith. But what if a state consents to be bound but it turns out the treaty it signed was ill conceived and malfunctioning in its operation?

This is apparently what happened with the Northern Ireland Protocol. Everyone knew a British Northern Ireland border was going to be problematic, but it was agreed so as to get Brexit done and revisit it if it were demonstrably shown to be malfunctioning. There is nothing unusual or dishonest in agreeing a treaty and amending it in light of experience, and Cummings is wrong to think it is cheating foreigners to agree something hoping to change it if it does not work, and he should stop behaving like a male chauvinist scorned.

It is not cheating because the intention to amend is not going to be done by unilateral action but by agreement of all the parties to the treaty, which is expressly permitted by international law.

The EU indicated that it is prepared to renegotiate the Irish Protocol in a way that as far as possible preserves a UK single market as it does the single market between the Republic of Ireland (EU) and Northern Ireland. The EU single market and the open borders and freedom of movement between the two Irelands was a necessary precondition of the Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement but that’s only one side of the equation that caters primarily for the feelings of the Catholic community. The other side of the peace equation has to satisfy the feelings of the Protestant Unionist community. The EU now understands this, and the hope is that the American president and Congress get it too.

The requirement that the Court of Justice of the EU is the final arbiter of legal disputes arising from the application of the Irish Protocol is not an insuperable problem. With a little creative thinking I don’t see why British Supreme Court judges could not be seconded ad hoc to the Court of Justice of the EU in cases from Northern Ireland to satisfy the independence and impartiality requirement of the Charter of Rights of the European Union, which governs all institutions of the EU including the Court of Justice.

Alper Ali Riza is a queen’s counsel in the UK and a retired part time judge

Click here to change your cookie preferences