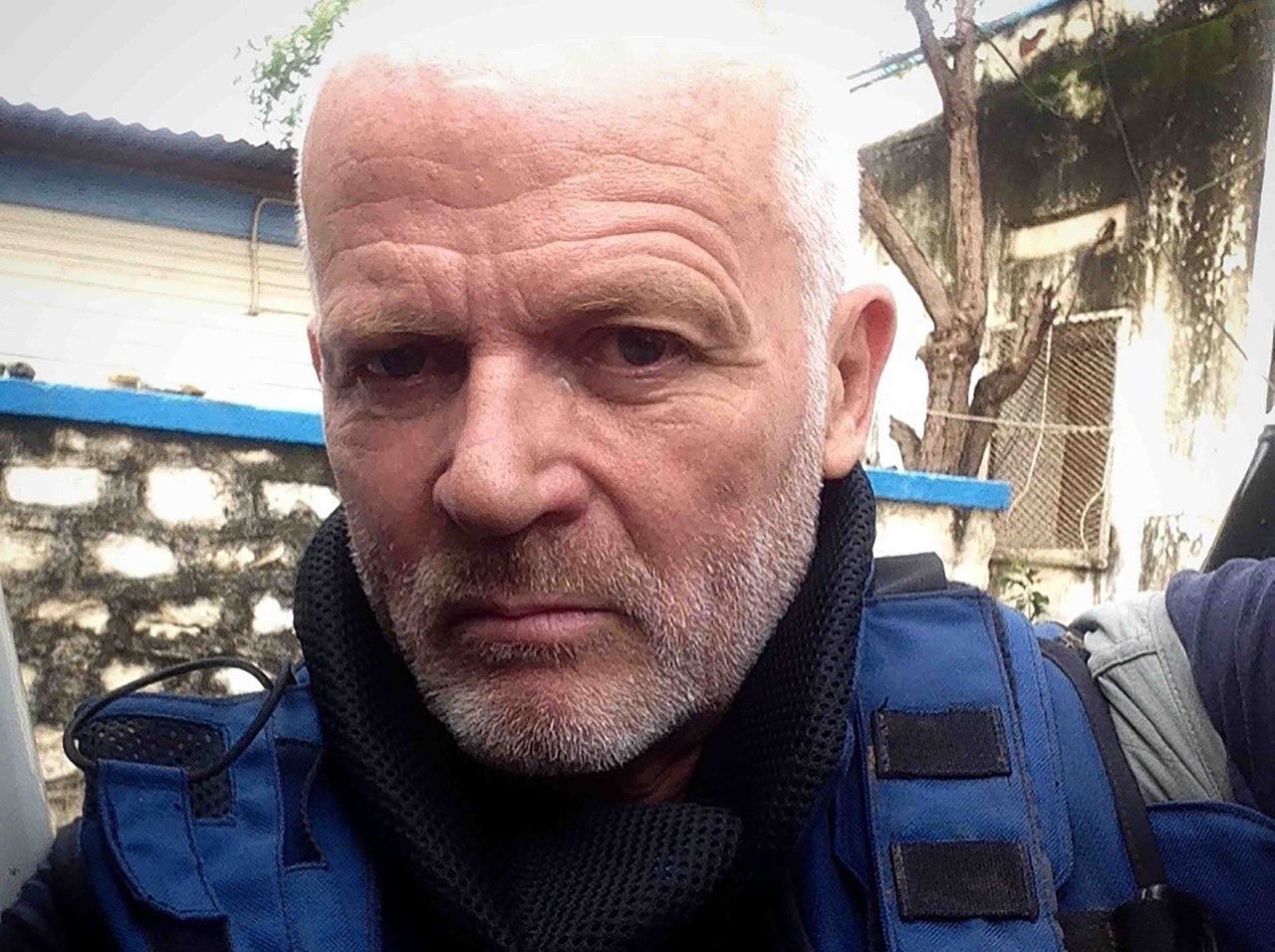

Having been to some of the world’s worst war zones one photographer now uses his lens to tell human stories. MELISSA HEKKERS meets a man telling the stories of those in Cyprus’ refugee camps, from a geneticist to a newspaper editor

Sebastian Rich has a bold heading on his website: A photographer of war and occasionally peace. But where would a war photographer who has been documenting our warzones for the past 50 years finds his peace? “I try and keep cynicism at bay,” he says as we meet online 48 hours after his most recent assignment to South Sudan. Attempting to delve into the person who has undoubtedly witnessed the worst atrocities human kind is capable of instigating, I find a rather private being, who reveals himself through the circumstances he has found himself in.

The acclaimed 67-year-old Briton turned to photography after running away from school at the age of 15. And after he joined ITN in 1980 he began to cover some of the world’s biggest breaking stories. Eventually he broke away and began pursuing a freelance career that has left him “with two hats”; a photojournalist and a humanitarian photographer. Is the latter that mostly concerns him these days after having worked with some of the largest humanitarian organisations over the past 20 years.

Cyprus has been his home for the past 25 years, a place where he finds solace, a place that allows him to have easy access to the east where he nowadays spends most of his time, and also the subject of his latest book, in which he documents the experiences of refugees in Cyprus.

“History repeats itself and that’s kind of the sad thing,” he admits. As an example he refers to his recent trip to South Sudan. “I’ve been going to south Sudan since before it was called south Sudan. If I showed you pictures of children with severe malnutrition in 2011 and I showed you pictures I shot three days ago, you would be hard pressed to tell the difference. For me,” he adds, “it can get terribly depressing. I was in Al Saba Childrens hospital in Juba photographing a child that unfortunately died in front of the camera a couple of days ago, but that happened to me the last time I was there, and the last time and the last time and the last time…”

What then, keeps a father of three going back to unchanged realms?

“I don’t know,” he replies, “I suppose, it’s a rather trite answer but it’s what I do, it’s all I’ve ever done. I have been covering the Palestinian conflict for most of my life, that hasn’t changed at all, if anything it’s just got worse and worse,” he pauses. “This time around in South Sudan it was particularly difficult to keep my enthusiasm going but in a way, it’s still there. I suppose that in a kind of naïve way I’m still trying to think that I may take that iconic photograph that actually changes a politician’s mind or makes Mrs Miggins from Chelsea put another 50p in the Unicef donation box. I have to keep that in my head otherwise, what’s the point?”

What he does is try and make it personal, relatable… and the tug of war between hard news and human stories is what prompted Sebastian to become a freelancer in the first place, using his voice to promote a reality that he feels confident with.

“I started off as an assistant fashion photographer and it couldn’t be further from what I’m doing now,” he says. Having spent a number of years working for TV, his life changed in 1991 when he was one of the first so-called photojournalists working with the US marines during the invasion of Iraq. “I filed lots and lots of stories by satellite,” he says. But on his return he saw the stories he’d shot for NBC news. “I looked at them and I thought to myself, that’s not what I saw, that’s not what I felt, that’s not what I heard. I feel that with a stills camera you change it (reality) less, you’re less intrusive into someone’s life or the environment that you’re in. With TV news, you can drop in a cut away, a wide shot, you can drop in something and you change the whole perspective of a possible truth. It’s a variation of a truth but I feel that maybe, naively, with a notebook and a stills camera, there’s a little dignity left in our profession.”

Rema Beshtawy 29yrs old a Syrian refugee from Lattakia ,Syia.

Rema is glad to be living in Cyprus with her mother, father and her son. She is working with a local NGO helping refugees and asylum seekers in Nicosia Cyprus.

For the past 20 years, Sebastian has been working for humanitarian organisations, which seems to have given him the space to address history and the world’s calamity in a different light. “What I love about working for them is that it’s not celebrity driven… it’s not about ratings, it’s not about selling newspapers… it’s about gathering content to tell stories about people”. It’s also here where he finds more meaning to his work. “Some of my work has gone to prosecute human rights abusers in the Hague tribunal so you’re actually feeling you’re doing a bit of good. I love working for UNHCR, Save the children, or Médecins Sans Frontières, or UNICEF because the story is about the people, with no other real agenda.”

Sharing stories about refugees and displaced peoples is at the epicentre of our conversation, the consequence of our wars, climate change and our actions as human kind.

“Trying to get messages across is difficult, especially with refugees because they’ve been demonised. Could you imagine if the Turks invade the island again? All of a sudden we’d become refugees, through no fault of our own, we’d lose everything overnight; most people can’t imagine that 99.9 per cent of refugees are in this situation, there’s one per cent that were Isis and al Quaeda who infiltrate refugee camps… I’ve come across these people but it’s a tiny, tiny minority… western governments demonise this tiny majority and demonise the rest of these people who have got nowhere to go,” he affirms.

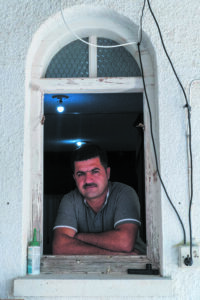

Hindran living in limbo over his asylum status

But it is not just about how he sees it. When Sebastian takes a photo he asks the person in it how they want to be seen. “I don’t want them to be scrambling around in the shit in a tent that UNHCR has provided; I want to see them how they want to be seen through my camera, especially women. When women refugees have escaped the horrors of whatever, I’ve found that a lot, not all, have managed to put a lipstick or a little bit of make up in their pocket. I only discovered this by accident, when I first asked woman in Somalia how she wanted to be seen. She suddenly vanished to another part of the tent and came back made up with a couple of pieces of clothing that were important to her. She had this beautiful stance, and I thought, that’s it, it’s about me giving them a little something to cling onto. For them to show their pride and dignity.

“A lot of photographers go out there to see people in distress, but we already know they’re in distress, they’re a refugee, they’ve lost everything, we know that, you don’t have to amplify that. What is nice to amplify is that they’re normal, like you and me.”

But what is normal has also changed over the years and really hit home when Sebastian was in Syria. Previously in Africa most of those he had come into contact with were farmers, and not educated. But suddenly in Syria “every time I went to one of the camps, there were judges, policemen, and nurses, everything that holds the fabric of society together. I was doing interviews with people with PhDs and Masters degrees, and it was a very different concept”.

And his latest book – for the UNHCR about experiences of refugees in Cyprus entitled Untold Stories – reflects another normal. “It’s very unique here in Cyprus,” he says, “in the two camps here you have Afghans, Cameroonians, Nigerians, there’s a big sort of culture clash and going to the centre of Nicosia you’ve got all sorts of nationalities… Once again, not everyone but a lot of people in Cyprus are very suspicious of refugees so myself and UNHCR came up with this idea about how refugees contribute to this community, they’re not just take, take take. We’ve got about 10 case studies where we profile a mathematician to a genetics scientist, a Somali girl who was editing a newspaper and we tell their stories as we try and give a positive spin.”

The book Untold Stories

Having three children of his own, Sebastian is also known for profiling children. “All wars and conflicts are horrible but as adults, as we like to call ourselves, we kind of get the reason why wars are happening… but children have no idea. So when a bomb hits their house or their mom and dad gets killed, it’s not only are they terrified, they just don’t know why. I think what struck me from the very beginning of my career was this confusion of not understanding what was going on.”

Once again he tells a story to make his point. “I once asked a little girl to draw a picture of her best friend in a Syrian refugee camp in Jordan. She presented this stick figure that had blood pouring out of it. When I asked her what it was she told me that it was her best friend; that they were playing football outside her house and that she was shot by a sniper and died.”

Although he was absent for his own children due to his line of work, one of Sebastian’s fondest memories is of working with children. “It’s just a story about a little girl who thought the butterfly tattoos on my arms where real. She wanted to take them off my arms and put them in her pocket because the refugee camp was a very dirty place. There’s lots of horror stories I can tell, this is not a horror story, its one of the sweetest things I think I’ve heard in my life, and it was something that made me stop in my tracks for about 10 minutes and just take stock of where I was.”

Any regrets? “Oh yeah, every single day of my life. But regret is a useless emotion because you can’t change the past, yet you can’t help it filtering into your mind. I could have done things differently,” he admits, “the problem is I started off in this profession when I was incredibly young, so you just say yes to everything and the trouble is that that mentality is still there. I guess I’ll keep going until the bones don’t transport me anymore.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences