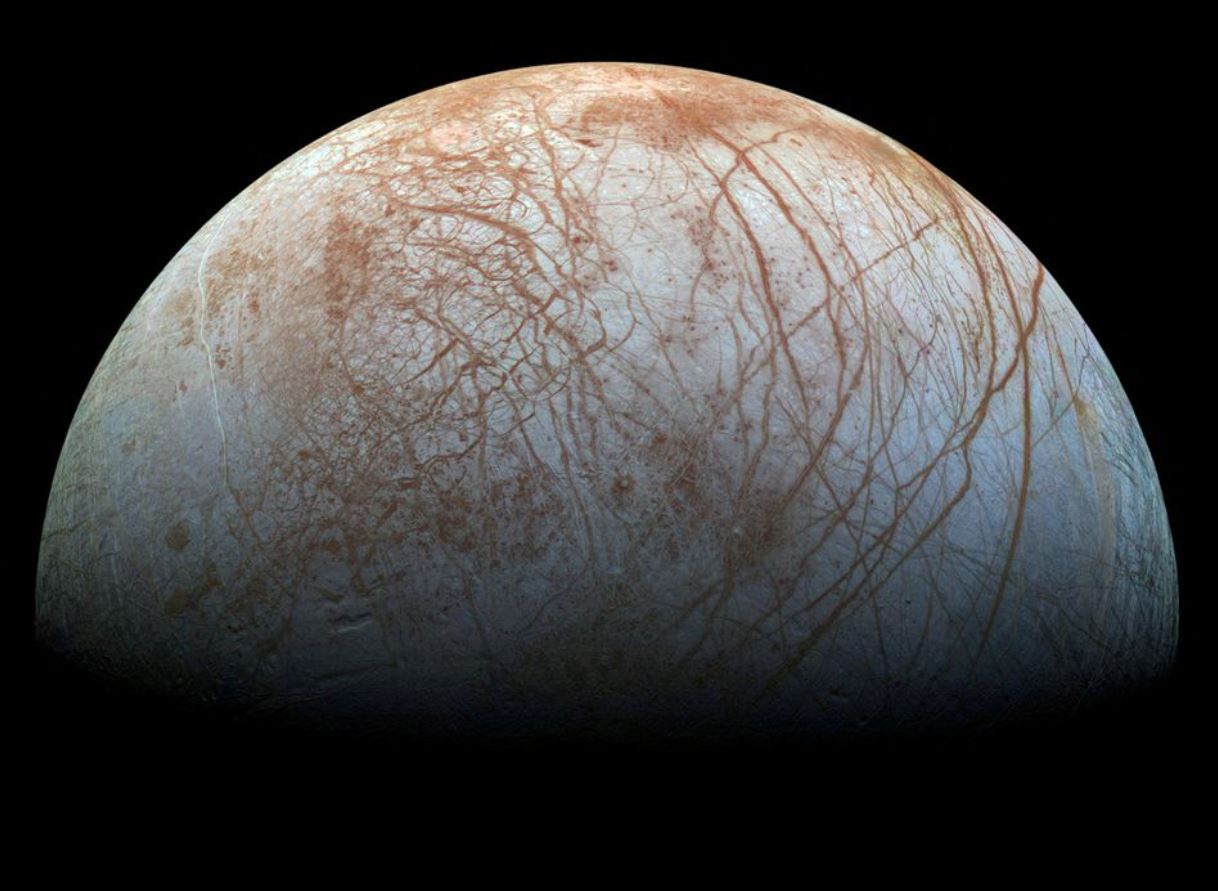

The uncanny resemblance between features on Europa’s frozen surface and a landform in Greenland that sits atop a sizable pocket of water are providing intriguing new indications that this moon of Jupiter may be capable of harboring life.

A study published on Tuesday explored similarities between elongated landforms called double ridges that look like huge gashes across Europa’s surface and a smaller version in Greenland examined using ice-penetrating radar.

Double ridges are linear, with two peaks and a central trough between them.

“If you sliced through one and looked at the cross section, it would look a bit like the capital letter ‘M,’” said Stanford University geophysicist Riley Culberg, lead author of the study published in the journal Nature Communications.

Radar data showed that refreezing of liquid subsurface water drove the formation of Greenland’s double ridge. If Europa’s features form the same way, this could signal the presence of copious amounts of liquid water – a key ingredient for life – near the surface of this Jovian moon’s thick outer ice shell.

In the search for extraterrestrial life, Europa has attracted attention as one of the locales in our solar system that may be habitable, perhaps by microbes, owing to a global saltwater ocean detected deep beneath its ice shell. Innumerable water pockets closer to the surface would represent a second potential habitat for organisms.

“The presence of liquid water in the ice shell would suggest that exchange between the ocean and ice shell is common, which could be important for chemical cycling that would help support life,” Culberg said. “Shallow water in particular also means there might be easier targets for future space missions to image or sample that could at least preserve evidence of life without having to fully access the deep ocean.”

NASA’s robotic Europa Clipper spacecraft is scheduled for a 2024 launch to further investigate whether this moon possesses conditions suitable for life.

The shallow depth of Europa’s potential water pockets – perhaps within six-tenths of a mile (1 km) of the surface – also would place them near chemicals vital for the formation of life that may exist on its surface.

With a diameter of 1,940 miles (3,100 km), Europa is the fourth-largest of Jupiter’s 79 known moons, a bit smaller than Earth’s moon but bigger than the dwarf planet Pluto. Europa’s ocean may contain double the water of those on Earth. Life first emerged on Earth as marine microbes.

Europa’s double ridges, sometimes extending hundreds miles (km), generally are around 490-650 feet (150-200 meters) tall, with the peaks about three- to six-tenths of a mile (0.5-1 km) apart.

Scientists have debated how they formed. Culberg was struck by their resemblance to a landform he knew from northwestern Greenland, with peaks about 6.5 feet (2 meters tall), separated by about 160 feet (50 meters) and extending about a half mile (800 meters).

“The Greenland double ridge feature formed from the successive refreezing, pressurization and fracture of a near-surface water pocket. We see two ridges, rather than one, because the shallow water pocket was also split in two by a fracture filled with refrozen water,” Culberg said.

The water pocket in Greenland was about 50 feet (15 meters) below the surface, likely less than 33 feet (10 meters) thick and about a mile (1.6 km) wide.

If the same process spawned Europa’s many double ridges, each associated water pocket could boast a volume similar to Lake Erie, one of North America’s Great Lakes.

“Between having two potential habitats and the fact that double ridges – and the near-surface water bodies they may imply – are among the most common features on Europa’s surface, it makes this moon a very exciting candidate for habitability indeed,” Stanford geophysics professor and study co-author Dustin Schroeder added.

Click here to change your cookie preferences