In a restless and wide-eyed eco-activist, THEO PANAYIDES meets a woman hoping for a new system, resigned to writing reports instead of poetry

It’s okay, sighs Paraskevi ‘Evi’ Christodoulou – having spent an hour talking about systemic problems, lack of opportunity, and the perils of being 29 in the world economy – “I’m still cautiously optimistic”.

About everything?

“About everything. There are people like me out there! If I exist, there must be others… They just haven’t – come out yet.”

All this is said with a laugh, it should be noted (laughs and giggles often punctuate her conversation; she seems younger than her 29 years, or at least goofier) – but it does speak to the larger question of what makes her interesting. Most people profiled in a newspaper have some history of high achievement, whether personal or professional, but Paraskevi hasn’t really had a chance to achieve very much yet. She does have a book of poetry out, The Diary of a Dead Soldier, a slim collection of her verse (in Greek) from 2007 to 2016 (a second collection, showcasing more recent stuff, is apparently coming soon). She’s also something of an eco-activist, having founded the Cyprus branch of an international organisation called Stop Ecocide.

Rebels blocking the street at Trafalgar Square

Mostly, however, it’s the kind of person she is that emerges most strongly, and vividly. A thinking person, a lively person – but also a restless person, an impatient person. “I’m aggravated easily,” she sighs when I ask what she’d most like to change about herself. “If someone can’t understand what I’m saying to them – or they don’t have enough imagination to imagine the bigger idea, the bigger picture – it’s hard for me to accept there are people who don’t get it.” She’s a fresh-faced person, a wide-eyed person; she’s also one of those people who change as they talk. At first, as we stand around making small talk (she insists on addressing me in the plural, as befits a young person talking to an older person), my general impression is of a tall, thin young woman, with a suggestion of gawkiness; as she sits down, however, switching to English, and begins to expound on the things that mean most to her, her whole demeanour seems to soften and bloom. Her brown eyes shine, her sense of humour bubbles up. One might say her inner life is deceptively rich – which of course is what you’d expect in a poet.

“Whatever it is that you love,

“Maybe a person? Maybe a flower?

“Don’t lean too hard on it, my darling.

“You’ll kill its blossoms, its fragrance.

“Whatever you love, leave it alone,

“To grow calmly, in peace and quiet.”

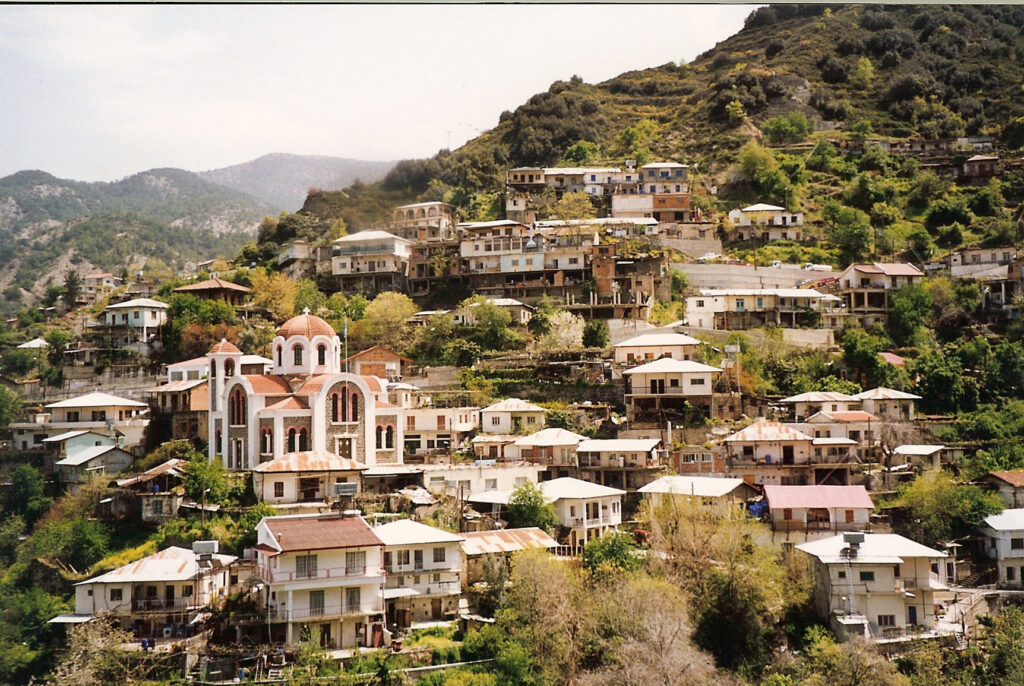

Those lines (translated, unofficially, from the Greek) are from a poem written on New Year’s Day 2016, signed ‘Dead Soldier’ which is Paraskevi’s poetic nom de plume. (The name originated in high school, as a slightly macabre persona: “I wasn’t feeling safe in high school”.) The poem presumably speaks to something in her, a need for space and an aversion to being ‘leaned on’ – and there’s also a desire for ‘peace and quiet’, which is actually all around us as we sit on the front verandah, the stillness broken only by the occasional barking of a nervous fox terrier named Layla. “Come to Moutoullas,” Paraskevi suggested on the phone – so I did, going up a winding mountain road to a village in gentle decline and a house (her parents’) with a glorious view of the steep-sided valley. She lives mostly in Nicosia, where her brother is restoring their mum’s old place – but it’s more like “I exist in Nicosia,” she adds with a laugh, spending weekends (and these past two weeks of Easter break) in the village.

This is where she grew up, by and large, though there were 80 pupils when she was in primary school (a regional school, admittedly) and now there are only about 100 permanent residents in total. Kalopanayiotis next door is bustling, but they had a benefactor (local lad Yiannakis Papadouris, who poured his fortune into transforming the village) whereas Moutoullas was left to fend for itself – and maybe that’s also played a role in shaping Paraskevi’s psyche, the fact that her childhood core, the mountain with its wide open spaces, is so vital to her, yet also so diminished; simply put, there’s nothing for her here. That said, she didn’t have a great time in school, getting bullied partly because her mum was a teacher and partly because of her own idiosyncrasies. “Everyone else had a teenage phase and I was already, like, 56 years old!” she recalls with a giggle. “That’s why I was so quiet. I was afraid to live, in a lot of ways, and that took me inwards. I’m very introverted as a person”.

Another of her poems – written in 2009, when she was 17 – talks about the one kid who’s in every classroom, the weirdo, the quiet kid who never makes eye contact. “This kid, that the others make fun of… / This kid, who doesn’t want to be like them”. Paraskevi doesn’t admit to being that kid, at least not in the poem – but she certainly wasn’t too articulate in those days, and “I wasn’t the smartest kid around… And the other thing that people found extremely ‘fascinating’ about me is that I wouldn’t talk about boyfriends and girlfriends when I was 14 or 15. I was like ‘I don’t care!’. I could see that everybody else cared – but I just wanted to leave Cyprus.”

Her first degree was admittedly in Cyprus (at the University of Nicosia), though in International Relations so at least it was outward-looking – then she moved to London for a Master’s in Understanding and Securing Human Rights, at the School of Advanced Study. The subject of her thesis was ecocide, defined as “a mass destruction of ecosystems” – hence the introduction to Stop Ecocide, whose rather quixotic aim is to make ecocide an accepted crime at the International Criminal Court, like genocide, so the main offenders (I assume they’re thinking of familiar villains like Brazilian president Bolsonaro) can appear in the dock as if they were war criminals. Paraskevi founded Stop Ecocide Cyprus last year, which in turn has brought her into contact with a number of local politicians; she works closely with the leader of the Greens Charalambos Theopemptou in particular, doing scientific work as a service provider. “These days,” she admits, “I write mostly reports, instead of poetry.”

Is she, then, an activist? Is that how to describe her? After all, it’s a fairly common character arc, the shy bullied kid who grows up to become an eco-warrior. But Paraskevi is a bit more complex than that, and a bit more intriguing. In the first place, she’s a committed Christian, so not entirely aligned with the neo-hippy ideals behind the Green movement. Secondly, and more importantly, she believes that trying to control what happens in life – which is, after all, an activist’s whole raison d’être, a belief in shaping the future – is naïve at best, delusional at worst.

“A small example,” she offers cheerfully, “a family example.” Her dad was fixing some steps in the river below (he’s the Moutoullas community leader, so he does a lot of maintenance work), the plan being that he’d help her brother in restoring the house in Nicosia once he was done – but he fell and broke his leg, so the other project was postponed. “It’s that simple,” says Paraskevi. “We all know it. Life is full of surprises, and the only permanent thing in life is change. You either embrace that, or you fight against life itself.”

It’s a great philosophy…

“It’s not just a philosophy. It’s the way I live.”

Surely she has a daily routine, though?

“I don’t have a routine – that’s the problem with me!” she replies with another peal of laughter. “I have various hobbies. Writing is one of them – it’s not just poetry, it’s also small novels and other stuff. I play musical instruments. Not very well, but I like it.”

How many does she play?

“In total? Um, 14. Not all at once!” she adds, giggling madly. (She actually plays three – piano, guitar, clarinet – pretty well, then the others are mostly variations on those.) She’s also taken up painting, largely as a result of moving to Nicosia and being unable to practise her late-night music playing. She appears to be a restless, imaginative woman who’s always seeking a creative outlet – also including travel (she spent a year in Japan as a student, calling it “the biggest experience of my life”) and self-improvement in general. “It’s just that I have this deep need of change,” she explains. “For myself – and to change me, as a person.”

What about settling down? Having kids? After all, she’ll be 30 in October.

“No. It doesn’t bother me.”

I only ask because there’s a biological clock, I note delicately. Hasn’t it started ticking yet?

“Really, there is? Where exactly?” she replies, looking around like a maniac – then collapses into giggles again. So much for the humourless activist.

Moutoullas only has about 500 permanent residents

It’s a bit like her poem, that need for space: don’t lean too hard on her, my darling. In an earlier generation the restlessness might’ve been knocked out of her by marriage, or (more recently) channelled into a high-flying career – but Paraskevi is a Millennial, and life has contrived a very weird set of circumstances for this generation. Even with a Master’s, she’s hardly working; Ecocide and the work with Theopemptou bring a certain income, but it’s all quite precarious. “I want to do something with ecotourism, but how? I really don’t have the money.” She sighs: “The opportunities are endless, but there’s no capital to start from. And the ones who have the capital don’t want to help. So that’s where we are in Cyprus – it’s general, not just me… Anyone who is 30 and below, they have the same problem.”

Few of her peers work in the fields for which they spent years studying; many eke out a living as baristas in coffee shops. Paraskevi’s parents are both civil servants (her mum, as already mentioned, is a teacher), but she shakes her head when I ask if she’s thought about following in their footsteps. “It would be such a big compromise… You have to deal with people who tell you ‘This cannot happen in Cyprus’, and you’re like ‘Why not?! You stupid people!’. Sorry,” she adds hastily, “I don’t call people stupid. Just, like – closed-minded.”

That’s a recurring theme too – the inertia we have here, the negativity, above all the lack of imagination. “I think generally our government lacks imagination,” she opines, speaking of environmental policy (again, sounding more like a frustrated creative than an angry activist). Why can’t the Akamas – for instance – be turned into a space for researchers to study biodiversity, and pay for the privilege? Why is there always this boring binary between development (meaning touristic development) and doing nothing? Why can’t we think outside the box? “I was born in the wrong place,” sighs Paraskevi at one point – but there’s probably no right place for someone of her personality type, the type who hates being hemmed in (anything “with a timeframe” in school – exams, writing essays in class – always gave her anxiety attacks) and plays 14 instruments just for something to do.

One more thing should perhaps be noted, lest we give the wrong idea: Paraskevi Christodoulou isn’t just some restless dilettante, she’s quite serious about what she does. The Christian principles are firmly held, ditto the human-rights principles – and indeed the two come from the same place, a belief in “structural values” like charity and altruism (and lack of hypocrisy, though she admits the Church isn’t always very good at that). What actually drives her? It doesn’t seem to be money, and it’s not quite ambition either. “It’s my superego,” she replies. “I love getting hugs from kids, when I help them… I’ve seen people being very grateful – and, in an ungrateful world, seeing that change is enough for me”.

What comes next, beyond a second volume of ‘Dead Soldier’ poems? Maybe a PhD, maybe a move abroad. (The latter seems quite probable; Stop Ecocide operates in about 30 countries.) But she’d like to see a change in the world, not just her own life; above all, “I’d like to express my hope that the younger generation will wake up eventually, and get started on new ideas… A new wave, a new system, a new – I dunno, something more humane”. Maybe she wants too much? “I do,” replies Paraskevi instantly, taking my warning as a challenge, and laughs: “Of course I do! C’mon!”. Is wanting too much the only hope, then, in a world that doesn’t offer enough? She’s cautiously optimistic about that too.

Click here to change your cookie preferences