In a life-long lover of music, AGNIESZKA RAKOCZY meets one of the island’s leading choreographers who transforms what life throws at her into dance

Several key events mark the life of Cyprus-based, Thessaloniki-born dancer and choreographer Andromachi (Machi) Dimitriadou-Lindahl, who last week celebrated the 25th anniversary of Asomates Dynameis, the dance company she founded in Paris and has been leading ever since.

The starting point was in 1970s Thessaloniki when the teenage Machi saw the American movie The Turning Point. The Herbert Ross-directed film was inspired by the story of Nora Kaye, his wife, who was a founder member and prima ballerina of the American Ballet Theatre. Focused on the world of ballet in New York, the film also starred the amazing Mikhail Baryshnikov, who had recently defected from the then Soviet Union. Regarded as one of the finest movies on ballet ever shot, the film made a lasting impression on the young girl viewing it.

“It was about an old ballerina and her daughter who also becomes a ballerina,” Machi, now 60, recalls as we sit in the house in Strovolos she shares with her husband of more than 30 years, the former Swedish ambassador to Cyprus, Ingemar Lindahl.

“When I saw it I was struck by its beauty. And even though I had seen some other films on ballet before this, it was so much more powerful that suddenly I knew what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I wanted to be a dancer. So I told my mother, who said it was impossible because we didn’t have money.” Heartbroken, the teenager took to her bed for three days, refusing to eat or drink, just crying.

Although Machi lost her father when she was just six she says his love of music had a strong impact on her life. “I remember my father in the kitchen on Sunday mornings listening to Mozart, Schuman or Schubert and pretending that he was a conductor.

“All the feelings I have for music, culture, choreography come from him, from these years.”

Her mother was another source of inspiration. As a widow, she had a tough time when Machi’s father died. “One of the best childhood memories I have is of waiting for her to come home from work and putting on some music she loved, tango or swing, as I listened for her steps in the corridor, the key turning in the door… and then we started dancing. It was our way of consoling ourselves for our loss…”

From an early age, Machi had an instinctive understanding of movement. She was always inventing new steps, realising as she did that this enabled her to express feelings that otherwise she would prefer to keep to herself. Yet the Thessaloniki of the 1960s and 1970s offered little to help a young girl become a professional dancer.

“Dancing was a hobby for wealthy girls whose parents could afford piano, ballet and French lessons. And as my mother said, we didn’t have money for this,” she recalls. Luckily, an aunt offered to pay for extracurricular dance classes so Machi was able to start getting closer to her dream.

“At that time there was no real dance academy in Thessaloniki so I was attending a normal school in the morning and had ballet and modern dance classes in the afternoon. Then I also joined a well-known folk group…

Finishing school at 17, the question arose – what next? She wasn’t fixated on becoming a classic ballet dancer, fearful she might be “too old for it and not trained well enough for pointed shoes”. Then just as she resigned herself to studies at the physical education academy, a family friend arrived from Athens and told her of the State School of Dance established and was run by pioneer of modern dance in Greece, Koula Pratsika.

“I packed and went,” Machi says. “My mother came with me. She had just managed to sell some land her father left her so there was some money. The first night we stayed of all places in Omonia and of course, I couldn’t sleep. And the next day I had an audition in front of the old lady herself, who was then in her late, late 70s. I had a very good reception – she said ‘oh, you Makedona (because I was from Thessaloniki), you are tall and beautiful, like a cariatyd’”.

Machi found herself in good hands. Both Pratsika and the women working with her were dedicated to dance and its survival. The year Machi entered the school Pratsika was still its director. Alter she was succeeded by Dora Tsatsou, who had studied with the great American modern dance choreographer Martha Graham.

“With Tsatsou, the American influence came in. Ours was a school in the making. But despite all these various inspirations, our teachers were also very focused on our own roots, and our roots were in in the rhythm, the folk dances and singing, in the ancient theatre.

“Our education was very rounded. They also taught us the history of music, dance and theatre, how to create a chorus for an ancient drama, modern ballet and improvisation. I was very privileged to be there.”

When her apprenticeship came to the end, her talent for creating choreography recognised, Machi was advised to apply to the Onassis Arts Foundation for a scholarship to study in New York with another great American dancer/choreographer, Merce Cunningham. Her application was successful and so she set off to the United States. Quickly, she realised that the Cunningham approach did not fit her. She was facing another key moment.

“The scholarship I got was enough to pay for half the life in New York so I had to augment it by working in a Hungarian pastry shop, living in a tiny room, while I continued to study. So many things to do, books to read, records to listen to, performances to see. But after a year I felt that NY was not for me. A day came when somebody broke into my room and stole my watch. I felt that I was changing. Then it happened. The Pina Bausch company came to New York to present Ariel at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. It was 1985 or 1986, and I went and seeing her company was like the film I saw at 15 when I collapsed on the bed crying. It felt like a thunderstorm. A revelation. I realised that this is where I belonged – to German expressionism.”

There and then, she decided she had to join the Bausch company in Wuppertal. Next day, she attended an audition and came close to being selected. She vowed to try again as soon as possible, said goodbye to New York and returned to Greece. She made several attempts to join the Bausch company, never quite managing to succeed. By her own admission, she just “wasn’t well enough prepared.” At a party in 1987 during the Thessaloniki Film Festival she met Ingemar, a dashing Swedish diplomat, newly arrived at the Athens embassy. Their encounter proved to be the third key moment in Machi’s life.

By then she was working as an assistant for Zouzou Nikoloudi, one of her former teachers in Athens and founder of the legendary Chorika dance company.

“When we decided to get married, Zouzou got very upset,” Machi chuckles. “She blurted: ‘What? You’re going to marry a diplomat? What are you going to do in your life? Receptions with champagne glasses in your hand?’”

Coming as she did from an upper-class background, Zouzou, she sensed, knew what she was talking about, and “here was I going back to everything that she had turned her back on!”

But Machi was undeterred by her irate mentor. “I felt in Ingemar I found everything I was looking for: the father, the stability, a gentle, educated, noble soul. I felt it was impossible to do otherwise. And besides, I was increasingly unhappy in my work.”

It was excellent training in memorisation and all aspects. However, “I was reaching the point where I wanted to experiment with my own ideas and was increasingly frustrated that she should have given me the space to do so but she couldn’t or wouldn’t.”

Soon after, Machi and Ingemar left for a new posting in New York where their first child was born, and where Machi continued to take dance classes. Then, on being posted back to Sweden, she started working again.

“In my experience if you are a dancer you either have your children late or you have a lot of money and nannies, but then I met the Swedish model,” she laughs.

“I went to this dance studio where they invited me to join them and I said I would love to, but I have a small baby. They just looked at one another and said ‘so do we’. Rehearsals were with babies sleeping in their strollers. We were dancing, nursing, having coffee and enthusiastically discussing projects. It was all integrated — shocking and liberating at the same time. Soon I was pregnant again and dancing until the end of my pregnancy and then we left for France.”

Asomates Dynameis

Machi found Paris to be much more difficult than Stockholm but her development continued there as well. It was in Paris in 1996, that she finally created her own company, Asomates Dynameis, and she has never stopped creating since then.

“The creation of this company, gestated for a long time in me. My direction was always to create dances, concepts and movements and visual installations …And I always had this deep belief that dance is more than just physical artistry, that the powers that move us are these bodiless forces, soul and energy that are invisible until they become visible and manifest. This is why the company is called Asomates Dynameis. It means Angels in Byzantine Greek.”

Machi’s work reflects personal experiences that she transforms into the universal language of dance. Many of these subjects can be painful – loss, abuse, nostalgia, struggle.

“This is what art is for me,” she declares. “You take what life brings to you and transform it. I can never work on a theme that I don’t feel in my guts. It is not a coincidence that in the last part of the performance called Breath (about climate change), there is a naked man enveloped in white plastic. He is simultaneously both an angel that can fly and the evocation of a death sentence because he is being asphyxiated.”

In Antigone, the work she staged to a standing ovation in Strasbourg in 2017 when Cyprus assumed the Presidency of the European Council, she views her protagonist not only as “a woman who decides to stand for her beliefs, coming into conflict with authority and paying for it with her life, but also [as]a person who wants to bring something together, something that is separated.”

In her mind, that something became Cyprus. “It was like ‘this is my brother and this is my brother too, and I want to bury him, so let me connect the two things, and the moral question is am I really a human being if I don’t perform this ritual of empathy for my brother’. So in my mind Antigone became a symbol of reconciliation, resistance to the narrative of authority and power, and as such I think it is well connected to the island.”

Describing how she approaches her work, she talks of the long hours of solitude, of the sketching and drawing, the taking of notes, of listening to music, of dancing, and improvising.

“There is a lot of self-observation involved, a lot of self-awareness. You play with senses, you touch, hear, look… you play with space, with objects and with memories. And then there is also the work with the dancers — a dialogue with them, absorbing their input. The older I get, the more input they [the dancers] give and the more I turn to dramaturgy direction, choreographic direction and less movement.”

She allows that there are things she can no longer do herself but when she sees them, she can recognise them as she leads the dancers and the phrases to where she wants them, to the culmination, the fulfillment of her joy in creating movement that moves us, the audience, to another plane.

It is, she says, “the magic moment where my experience, my memories and my vision meet with what a dancer is giving me.

“I need humans to tell my human stories and what emerges becomes not only my story but their story as well. It is very much a co-creation. We open our hearts to each other That is why I say dancers are my body and soul and I love them all very much. But they don’t decide what we do. I do.”

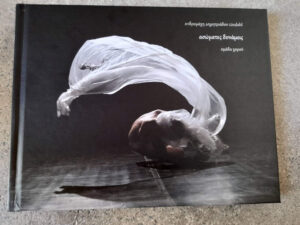

Since 2004, Asomates Dynameis Dance Company is based in Cyprus. To mark its 25 years, Armida Publishing House has published a book of essays and illustrations highlighting Machi’s work and some of the company’s outstanding productions

Click here to change your cookie preferences