One of Britain’s greatest victories in World War II

By Colin Smith

Today is the 80th anniversary of the start of the Battle of El Alamein named after a scruffy little coastal railhead of that name 160 miles east of Egypt’s desert frontier with Libya that was then Mussolini’s largest remaining Italian colony. It lasted twelve days and by November 4, after three years of hostilities, Britain had won its first major land victory in World War Two. “Not the end, not the beginning of the end,” said Winston Churchill, “but the end of the beginning.”

And yet the seeds of this victory may well have been sewn some three months earlier. Bernard Montgomery’s name would be linked to Alamein as firmly as Wellington’s to Waterloo. But can it be true that it was German intelligence who accidentally helped win it for the British with the aerial assassination of his rival, the popular desert veteran Lt-General William Gott, Churchill’s own preference as commander of the 8th Army?

Pilot Jimmy James

Certainly General Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff and Britain’s most senior soldier thought so. “It seemed almost like the hand of God suddenly appearing to set matters right where we had all gone wrong,” he confided to his diary when he considered the implications of Gott’ death. “Looking back on those days with the knowledge of what occurred at Alamein and after it, I am convinced that the whole course of the war might well have been altered if Gott had been in command of the 8th Army. I don’t think he would have had the energy to stage and fight this battle as Monty did.”

On August 7, 1942 six Messerschmitt 109 fighters ensured that Gott was never going to get the chance when they intercepted an RAF Bristol Bombay, a slow twin-engined transport with a fixed under carriage and 19-year-old Sergeant Pilot Hugh Glanffrwd James at the controls. The aircraft was bound for Cairo with 14 recently wounded stretcher cases plus Gott who had almost missed the flight and was due to have his second meeting with Churchill in the space of 48 hours. The prime minister and Brooke were visiting Cairo to investigate what Churchill called ‘the inexplicable inertia’ of General Claude Auchinleck’s Middle East Command which in June had seen the 8th Army surrender Tobruk to the El Alamein line – the last major defensive position before Alexandria and Egypt’s Nile Delta. Here Auchinleck fought Erwin Rommel into a stalemate and both sides waited for reinforcements.

Remarkably, the route the Bombay was flying between a frontline airstrip at Borg el-Arab and Cairo was considered so safe that even Churchill, who had had his first meeting with Gott two days before near Alamein, returned to Cairo the same way and without a fighter escort. After take-off transport command’s only concession to being in a war zone was to bring their desert painted aircraft down to fifty feet and keep to that altitude until they were safely out of range of German fighters.

Gott’s flight had been airborne for about 15 minutes when its teenaged pilot (he had grown a year older on his enlistment form) first heard the bangs and clatters he initially mistook for engine trouble. Then he began to smell the smoke and through his windscreen saw the broken orange lines of tracer fire darting ahead followed by a glimpse of the Messerschmitt that probably fired at them peeling off to his right, a blur of yellow markings on its belly and nose.

British infantry fighting through the dust and sand in 1942

Under fire for the first time, some 20 years later he admitted in an interview for a book I was researching that he was scared stiff. “I was yellow, no other word for it…all I wanted to do was go and hide. Then suddenly it was like rugby, I went into wild Welshman mode. I thought, I’m not going to let the bastards get me. I’m going to land this damn thing.”

He ordered his crew to prepare for an emergency landing. The navigator went into the fuselage and helped the sergeant medic and two aircraftmen there prepare the stretcher cases for fast evacuation. This involved lifting the rear door off its hinges to prevent it jamming in a bumpy touchdown. Some accounts have Gott, who had been sitting on a little jump seat near the door, helping out with this.

By now the Bombay was well alight. Fuel from a punctured tank in its high wing was feeding a thickening curtain of flame between fuselage and cockpit. As he looked for a place to land James realised the joystick had become so hot it was blistering his hands. When the windscreen began to melt he ordered the opening of the cockpit’s escape exit – a trapdoor behind his seat where the radio operator was slumped ashen-faced clutching a wounded arm.

James himself was quite unaware that he had a splinter in his back and a bullet though a calf. Somehow he brought the aircraft to earth down a gentle downwards slope as he wrestled with its red-hot controls to stop it ground looping on its back. When the Bombay hit a patch of soft sand it brought its speed down to about 20 mph and he felt waiting for it to come to a complete halt was out of the question. Better to try and rescue the wounded before the Luftwaffe returned to the attack. Yelling at the crew to start throwing the stretcher cases out he left his controls intending to help them do it. This probably saved his life for the next burst of fire shattered the instrument panel.

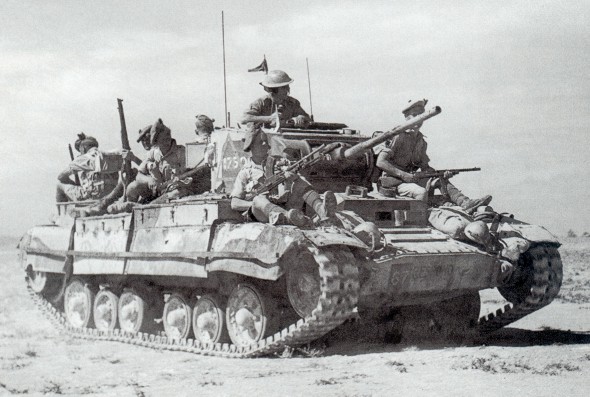

A Valentine tank in North Africa, carrying Scottish infantry

The cockpit was now full of flame and smoke, its floor buckling with the heat. Dazed and with the thump, thump, thump of the Messerschmitts’ cannon fire in his ears James dropped through the escape hatch. As he crawled clear the Bombay began to settle on its belly, flames dancing along its fuselage. But once out to his horror he discovered only four others had been so lucky. Sixteen out of the 21 aboard including Gott and all but one of the stretcher cases died after becoming trapped in the smoke-filled fuselage when its door, which for some reason hand not been taken of its hinges, had become buckled and impossible to open from either side.

James, who became the youngest ever recipient of the Distinguished Flying Medal for the cool and courageous way he handled his crippled aircraft, decided he was the least hurt of the survivors and went to get help. He walked a mile or so before he was picked up by a passing Bedouin who placed him on his camel and a couple of hours later was able to attract the attention of a curious British vehicle patrol. They delivered him to a military hospital but though lapsing in and out consciousness he insisted on guiding a search party back to the wreck where he knew the other four wounded survivors probably had little if any water.

The grave of Lieutenant-General William Gott at the El Alamein cemetery

Before his departure some of the medics who treated James’ wounds – he eventually had three operations and would be in and out of hospital for the next four months – found it hard to believe he was old enough to have been flying a general’s plane in the first place. James himself was always rather puzzled why, so well into RAF air space, the Luftwaffe risked strafing a downed aircraft. It was unusual for the desert war where a certain reciprocal chivalry prevailed even against legitimate targets like the Bombays which, besides evacuating wounded, delivered arms and ammunition. Did they really know Gott was aboard?

Or was it sheer happenstance that six Messerschmidt 109’s wasted their ammunition on a small transport aircraft that happened to be carrying a general who boarded at the last minute?

James remained in the RAF until 1965 but it was not 2005 that he learned the truth. At a meeting of German and British veterans he discovered two of the fighter pilots who shot him down. Former Unteroffiziers Hugo Schneider and Emil Cade told him they had been briefed, probably because of some kind of radio intercept, that somebody important appeared to be aboard the flight. The German fliers had wondered if it might be Churchill himself who could rarely resist a photo opportunity and was known to be in Cairo. Only when they returned to base some 20 minutes later did their commanding officer reveal that their target had now been identified as ‘Strafer’ Gott, originally nicknamed thus by his British contemporaries after the Kaiser’s World War One slogan Gott Strafe England (‘God punish England’).

Cyprus-based Colin Smith is the author with the late John Bierman of Alamein-War Without Hate, published by Penguin.

Click here to change your cookie preferences