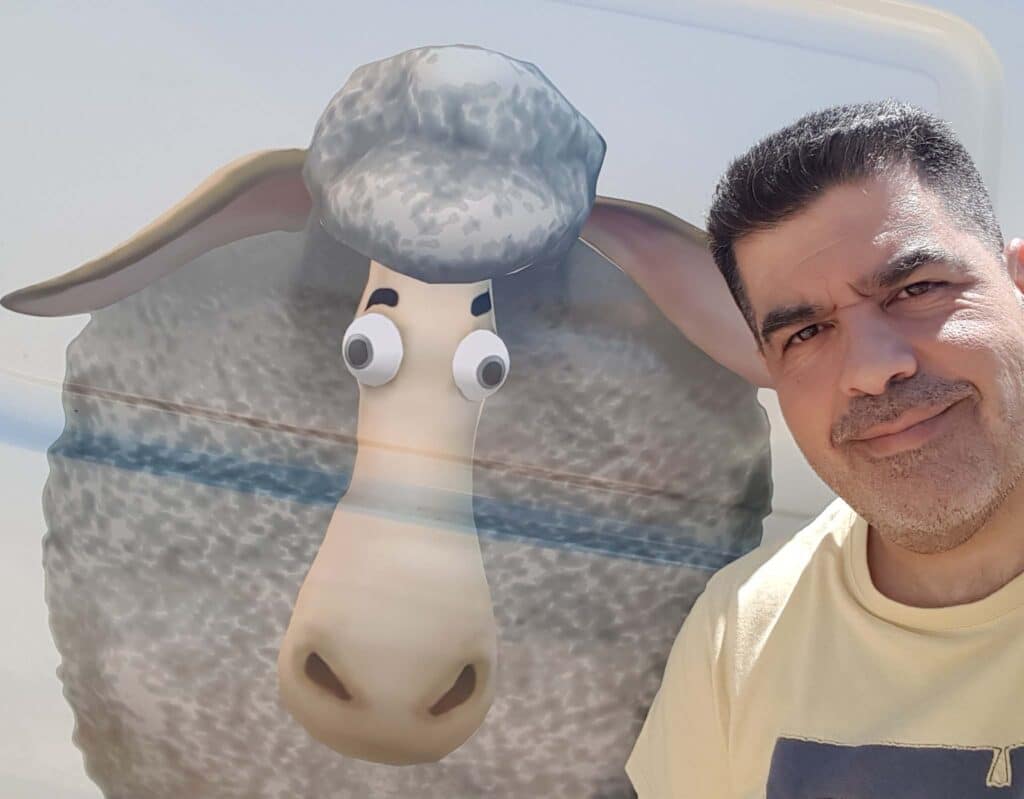

The man who runs a successful business selling homemade halloumi out of his van

A career change is never easy. Many of us consider it, even attempt to turn it into reality, but, alas, for most people it remains a dream.

Former Cypriot commercial airline pilot Pantelis Panteli, however, has proved that, when armed with patience, good will and, why not, a handful of sheep, radically changing one’s life is not impossible.

With planes now a thing of his past, Panteli has gained quite a reputation in Cyprus among halloumi connoisseurs.

Nowadays, he drives around the island in his van, aptly named ‘Kouella’ – meaning sheep in Cypriot, rather than Greek – selling not just fresh halloumi, but also anari, ayran and yoghurt.

“It all started when the airline I was working for, [the original] Cyprus Airways, was rumoured to be on the verge of bankruptcy. Along with many other people, I had to think of a Plan B,” Panteli told the Cyprus Mail.

“I could continue to work as a pilot, but I had to move abroad. That was not what I wanted.”

He wanted to do something in Cyprus and finally settled on making halloumi. The timing was right. Panteli decided to give halloumi-making a go right before the cheese was granted protected status (PDO) from the European Union.

The registration of halloumi as PDO, which took place in 2021, allowed producers of the national Cypriot cheese, renowned around the world for its characteristic texture and suitability for serving grilled or pan-fried, to benefit from the PDO status.

“Making a product that no one else in the EU was allowed to make represented a great opportunity for me,” Panteli said.

Panteli’s family never produced cheese professionally, but, nevertheless, he started learning the trade at a young age.

“I remember making small batches of halloumi with my father when I was young,” he said. “Never for other people, just for our family. But at that time, I didn’t think it could become a job for me.”

Despite his popularity and his dedication, Panteli is not currently allowed to sell his produce to supermarkets, nor can he supply restaurants.

“The current policy for people with small sheep farms like me prevents us from supplying the big retailers in Cyprus.

“I applied for a permit to produce halloumi and agriculture ministry officials came and inspected my farm. They found that I was within the law and that I respected the PDO specifications. I am legally allowed to produce halloumi and call it that,” he said.

Under the PDO regulations, 25 per cent of the milk in halloumi, a percentage that will rise to 51 per cent in 2024, should come from sheep and goats, with the remainder from cow’s milk.

Up until recently, most producers used only or a large percentage of cow’s milk, claiming it is how the majority of consumers prefer their halloumi.

“I produce it the right way, they way it has always been produced. That is why I can call it halloumi,” Panteli said.

“However, I have been told that I can only sell directly to the consumers. I cannot sell my product to supermarkets and I cannot supply it to restaurants.”

Panteli said the law in Cyprus is structured in a way that makes it necessary for sheep farms to only produce milk, thus leaving the production of halloumi exclusively to dairy plants.

That said, he does not plan to take the matter to court.

“It would take too much time and too much energy from me, whereas I want my efforts to focus on making the best available product for my consumers,” he said.

However, Panteli is well aware of the quality of his products. His big plan is to find a way to export his halloumi, sure that it will be a success.

“I want to export to niche markets abroad, to places that I know can appreciate quality. Israel could be an idea, as well as Qatar for example,” he said.

“I think that people over there could recognise the difference between store-bought halloumi and the one I make.”

Panteli said the mass production of Cyprus’ national cheese has brought some side effects to its taste and its quality.

“I personally know companies that collect unsold halloumi from retailers and boil it all over again to sterilise it and to re-sell it.

“Once you process any produce more than once, you compromise on everything, from texture to appearance, from taste to freshness. You will not get quality.”

Despite an uphill battle to see his status of halloumi-maker recognised in Cyprus, Panteli remains optimistic for the future.

“I want to sell to individuals here in Cyprus, as well as to markets that recognise and reward quality abroad.

“Like anything fresh, my halloumi needs to be consumed in a matter of days. That is how fresh produce works and there are people who understand and appreciate this.

“I believe there is always a market for good, honest and clean products, made with dedication and with love. That is why I keep doing what I do and that is why, in my opinion, it was worth changing my career for.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences