Thanasis Nicolaou’s mother has fought cancer twice. But her biggest battle is uncovering the truth behind her son’s murder.

In an interview with the Cyprus Mail, Andriana Nicolaou opens up about her 19-year-long fight to prove Thanasis did not kill himself.

Andriana Nicolaou may be small in stature, but her strength and determination are all-consuming. It is hard to believe that this powerful woman who has become proficient in all things legal, criminal and pathological is 75 years old.

Her home, perched on a hill in Limassol overlooks the army unit where her son served his national guard duty.

It was on that site he endured horrific bullying and witnessed what likely led to his killing: drug use and dealing at the camp site.

His “mistake” was that instead of getting involved, he chose to report it. A day after he spoke out, he was found dead under Alassa bridge.

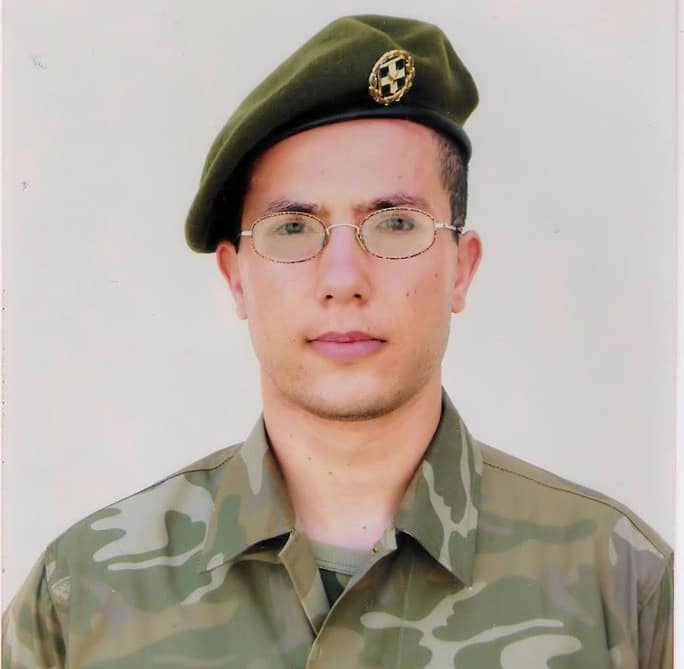

That was back on September 29, 2005, when Thanasis was aged 26. He would be 45 this year but he was killed three months into his army service.

Andriana spoke to the Cyprus Mail, afew days after the cabinet appointed two independent investigators to look into the case, and just a few weeks after a third death inquiry ruled that he was indeed murdered.

She smiles at the symbolism that the lawyer shares the same first name as her son – Thanasis Athanasiou. He will be collaborating with retired Greek police lieutenant Lambros Pappas.

For 19 years the authorities have insisted Thanasis killed himself. They told Andriana “it happens” and she should “just accept it.”

She was incessant, and still is. “How could he have jumped off 30 metres from the bridge and his body be unscathed?”

By unscathed, she means he did not have any visible perforations which would be expected from such a powerful drop onto the pebbly terrain under the bridge.

Andriana recalls how when she returned from the morgue, there were three vehicles with army officials waiting to talk to her.

“I thought they wanted to help me. But I realised through their questions that they wanted to find out what I knew. What Thanasis had told me.”

The latest criminal investigation carried out by Savvas Matsas and Antonis Alexopoulos paint a very different picture from the one drawn up by the state pathologist Panicos Stavrianos, who called it a suicide.

Matsas has gone public to say he believes there were three people involved in the killing. One who held Thanasis’ hands behind his back, another who beat him and another who eventually strangled him.

His family suspect he was forced to knock back the beer in the empty cans found in his car. Matsas’ report suggests the person who threw the punches may have been wearing boxing gloves. Thanasis suffered extensive internal injuries.

The sand which filled his mouth point to the idea the violence unfolded by the beach and his body later moved to Alassa.

“They told me the artery on his leg had been cut,” Andriana says as she flits through the autopsy pictures. The images themselves were incriminating for the findings, as Thanasis’ right leg is hidden underneath his left one in the picture.

As such, the injury remains hidden from sight in the official pictures. Andriana’s suspicions were raised, however, when she picked up his clothes from the morgue and saw her son’s sock was drenched in blood.

“It was these pictures that kept me fighting all these years.”

Andriana looks out of the window where the army barracks linger in the background. “My son went to serve his country. They say they’ll train them against the enemy – Turkey. But the real enemy was within.”

With a total of four children, Thanasis was her second child. But she says he did not take after her or her husband’s demeanour.

“He had something special about him. Like he was sent by an angel.”

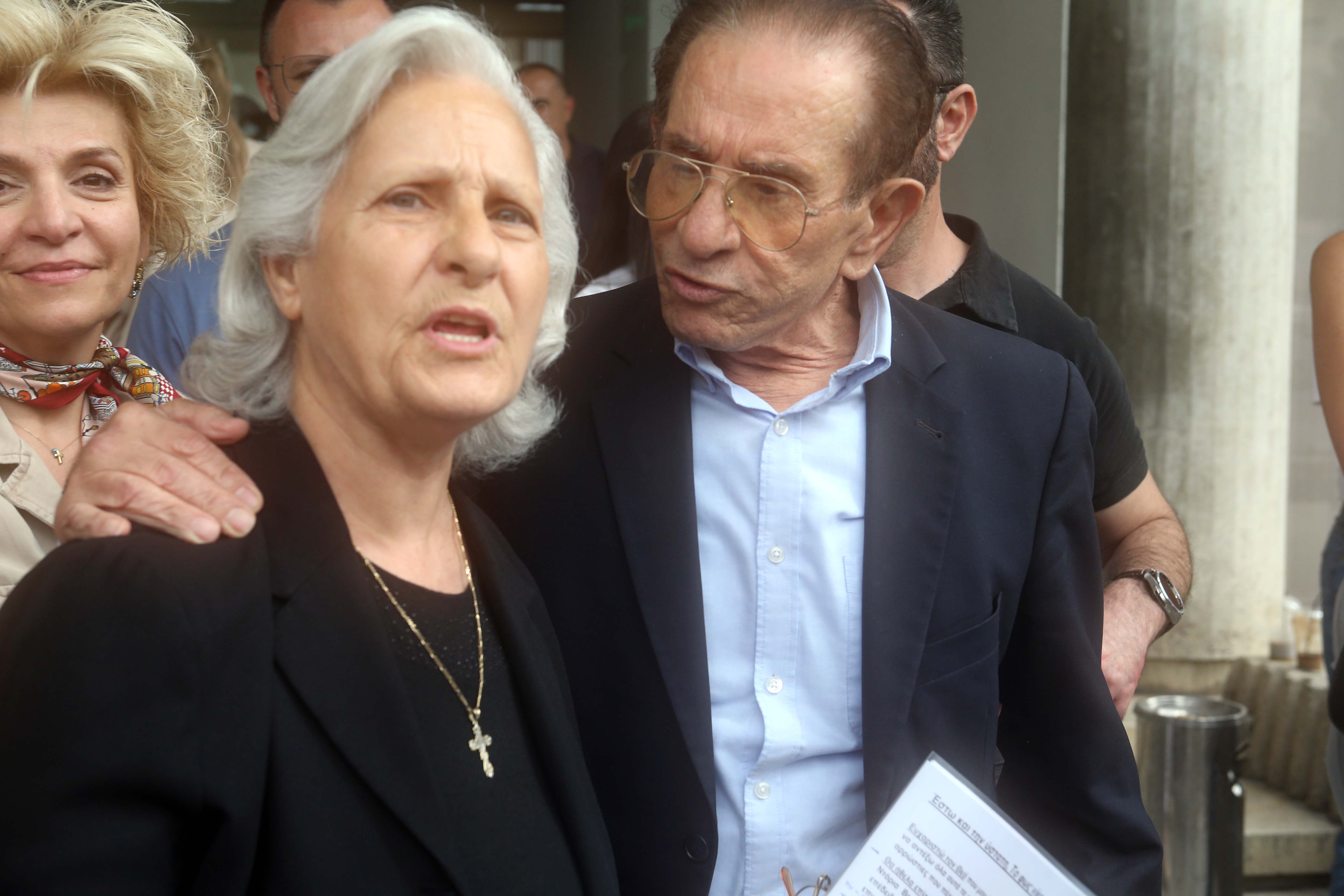

Thanasis’ father Charalambos is the polar opposite of Andriana. He is far quieter and flits in and out of the interview. Aged 81, his voice is often shaky, and in stark comparison to his wife’s powerful tone, he sounds horrifyingly perplexed when recalling the injustices.

But neither of them can ever escape the shadow of everything that has happened. Every family celebration, including even one of another son’s wedding and the arrival of her first grandson “have been enveloped by this cloud”.

“This has destroyed the whole family,” Andriana says as her voice breaks.

“Thanasis dreamed of getting married and having children. But they killed him.”

She talks about her son’s architectural drawings and beams with pride. “His work was impeccable. He was so good at what he did. The first time he got paid for his work, he was so excited. He couldn’t wait until he finished the army to open his own architect’s office.

“And then they killed him.”

Her eldest son who came with her to the crime scene had already served his time in the army. Her youngest son was exempt after Thanasis’ death. Her daughter is the youngest in the family, and all have paid a high price in their suffering.

The plan Andriana envisioned for her Limassol home was starkly different. It was supposed to house her four children and their families. After years of hard work in Australia, they thought they would settle back in Cyprus, and so they returned to the island in 2003.

Two years later, Thanasis was found dead.

“When I saw his body, my life stopped.”

Since then, it has been an endless fight. Against the legal service, against the police, against the army, against the courts.

The injustices which have been paraded before this family are grotesque.

They have seen people implicated in the poor handling of Thanasis’ case rise through the ranks. They have been called crazy, gaslit and mocked for their faith.

They have seen state pathologist Panicos Stavrianos become elected as Akel MP only months after ruling that Thanasis committed suicide.

They saw Stavrianos sit on the House human rights committee of all places. They watched him get re-elected and serve a total of 10 years as a lawmaker.

They then watched him seek a third term in parliament, this time on the Green party ticket. And that was a year after the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) decision found Cyprus’ investigation into Thanasis’ death inadequate.

The ECHR’s ruling played a monumental role. It left district courts with no other choice but to accept the family’s request to have Thanasis’ remains exhumed.

And as such, in 2020, they saw their son’s remains dug up from the ground, as they still begged for answers over his death.

Andriana has chased after every government official possible, ran after every media outlet (long before it became popular to talk to her and she was desperate for someone to hear her story).

She has not had it easy. Beyond the horrors she faced, knowing that her son fell victim to a violent death, she was shunned, ignored and labeled as crazy for refusing to accept that Thanasis had committed suicide.

She has also battled against cancer twice in the past 19 years.

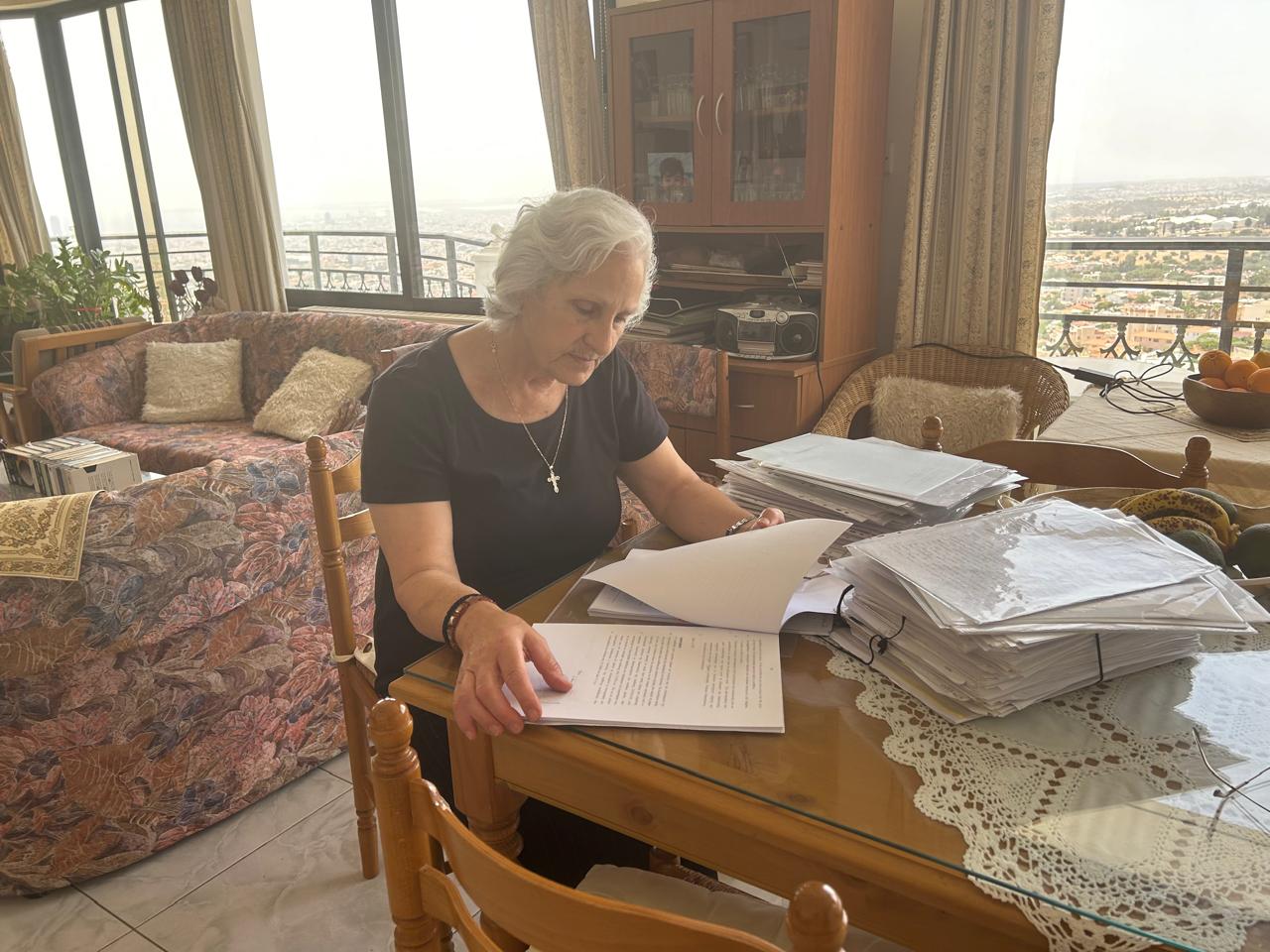

It is impossible to grasp how long these years have felt, but the stacks of paper piled up on the living room table tell the story.

“This isn’t it. Come, let me show you.”

She leads me to her bedroom where two bookcases are bursting with box files dating back to 2005, rows upon rows of them stacked next to each other, documenting every single letter, report and finding of the investigations surrounding her son’s murder.

Before I can even begin to process just how much there is, she points to more folders. These ones are stacked with papers far more personal. Her poetry.

“I wrote these and wept. I cried and cried and cried. All these years, I lost my son.”

Her poems were part of her grieving process, where she prayed for answers and tried to come to terms with Thanasis’ murder.

Her eyes, sharp, don’t miss a beat. In the 19 years which have elapsed since her son’s death, she has familiarised herself with law, forensics, pathology, criminology, media and every other specialty she had to master to fight for justice.

“I save every single article that has been written about my son. I download them though, because sometimes they delete them,” she tells me with a pointed look.

Her phone rings incessantly. Call after call, she never gets a break. “They killed my son,” she repeats so often, when people probe.

After one call with a journalist, she remarks rather sadly, that none of these people were here for her so many years ago when her fight was far more lonely.

“They called me crazy,” she says. “But I knew my son.”

Indifferent to the gaslighting she was put through by so many, she ploughed on incessantly.

Some told her she was brainwashed by religion, another top government official urged her to forgive the culprits. A cynic may think they were trying to dissuade her from pushing the way she did. But she was relentless.

“Bring me the murderers in front of me and then we can talk forgiveness.”

She recalls dates, wordings and letters off the top of her head. During court proceedings, she could easily be mistaken as one of the lawyers. Her box file on the ready, often times knowing where to find each document that was being discussed.

She would scroll through her phone during breaks to see what news outlets had written about the case so far.

The woman has not paused for 19 years.

“Have you ever processed the enormity of how much your life has changed? That this is your daily life?” I ask.

“If I do that, I’ll go crazy,” she says. “It’s better for me if I keep going. Until the day I die, I won’t stop.” Her fight has certainly been endless, but does she hope for light at the end of the tunnel after the coverup for almost two decades?

“Even now, the light has shone in the darkness,” Andriana says over the third death inquiry of her son’s death on May 10. She recalls how some doubted the judge Doria Varoshiotou, seeing a woman in her 30s sitting in the top post of the court room.

“And yet, she was the one that let the truth shine. She took me out of the hell I endured for 19 long years, as I tried to restore my son’s name.”

This is because it was the first time a court in Cyprus called her son’s death a killing, attributing it to strangulation.

Andriana shrugs off many of the epithets she is most often associated with such as ‘brave’ and ‘strong’. She cares little for these words and repeats: “I did my duty as a mother.”

At the time, she says she had two paths: despair or fight. But she was so sure over what happened to her son that she could not be silenced.

“I see him sometimes in my dreams. He guides me.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences