Outside every door is a reminder of our national struggle. An authority on our island’s street names explains why

In the UK, the most popular street names tend to reflect directions, places, and jobs: North Street and West Way; London Road and Manor Place; Mill Lane and Baker Street.

In the US, streets are often named for nature (Oak Avenue or Maple Drive) or numbers (2nd Street, Fifth Avenue).

In Cyprus, however, things are very different.

Here, on an island that’s battled for decades with its identity, many of our street names honour our recent past: a living memory of our troubles. Whether we’re commemorating political leanings, fallen heroes, or the villages we once called home, our streets tell the story of an island that will never forget…

“From Eleftheria Square to Markou Drakou to Kythreas, our political, economic, and cultural narrative is strongly reflected in our street names,” says Stella Theocharous. “Our streets tell the stories of our struggles, our heroes, and our displaced communities. They mirror how we see ourselves. Outside every door, we have a living memory of our island’s ongoing fight for freedom.”

An academic who has written the definitive text on the street names of Nicosia, 52-year-old Stella has long been fascinated by the names of Cyprus’ streets.

“Walking our alleys and avenues, our streets and squares, the connection between their names and our national narrative is obvious. Every one of our cities, for example, has both a Makarios and a Grivas Digenis Avenue. I often think it’s ironic, that in my hometown of Limassol, these two roads named for political figures who ultimately became enemies, actually cross one another!”

“Cyprus,” she continues, “is a country with a complex and complicated past – not the kind of place you’d find a Rose Lane or a Meadow Drive! And not only is this captivating, it’s also an area ripe for research.”

In 2018, Stella began looking into the street names of Cyprus, focusing on those of Nicosia.

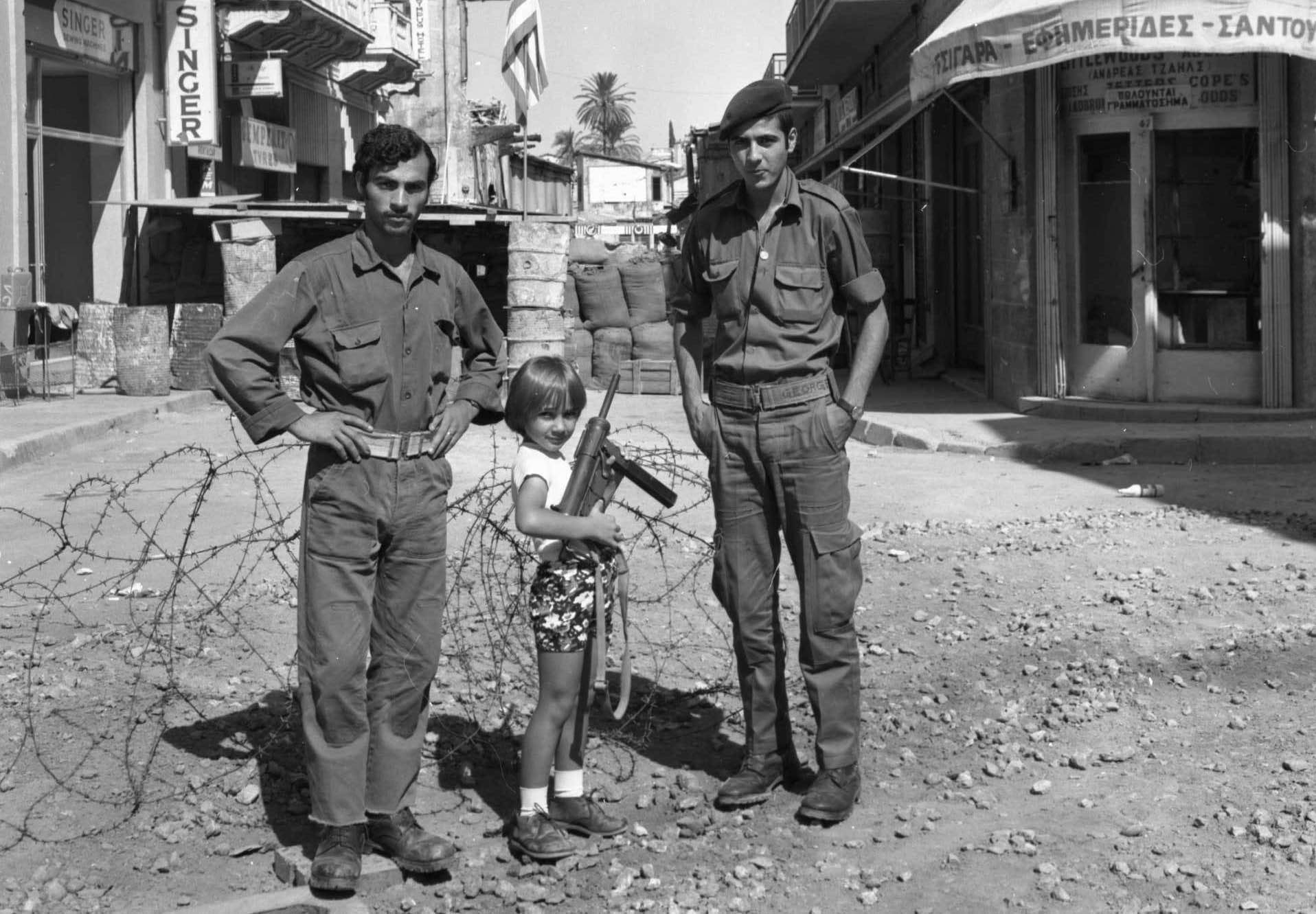

“All the big things happen in the capital; this is where rulers make the decisions and policies,” she explains. “And Nicosia’s ever-changing streets, its ability to expand only in three directions, its many dead ends – these reflect the city’s unique turmoil.”

In the course of her research, Stella spent weeks in dusty basements; months in windowless archives. Supervised by the well-known Professor of Cultural Geography Maoz Azaryahu, she visited the British National Archives in Kew and the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh; read countless books written by ancient travellers to Cyprus.

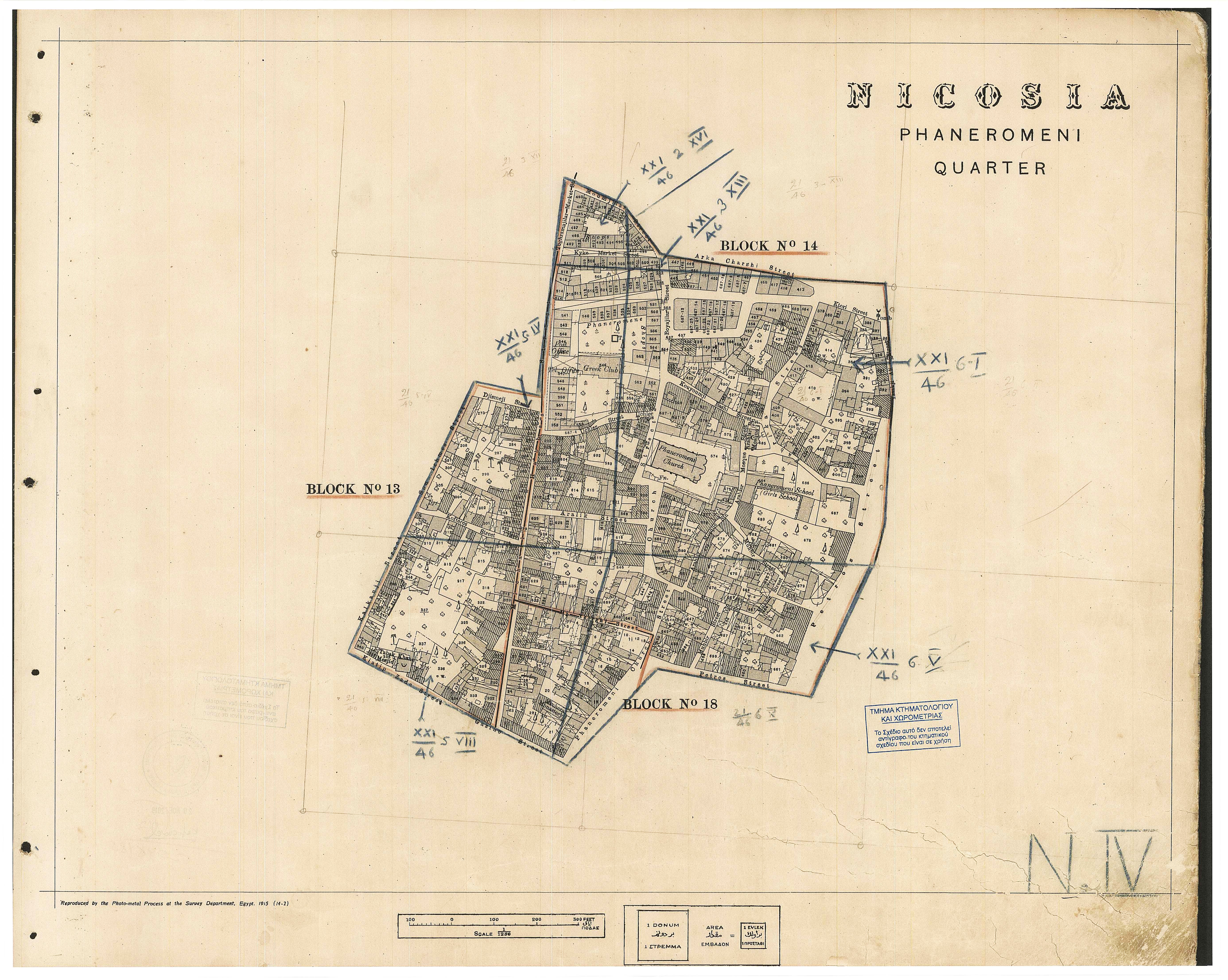

At the Nicosia Municipality she uncovered information from the very start of the organisation in 1882 when the first mayor, Christodoulos Severis, was appointed. With the help of the Cyprus Land Registry she traced the 1915 cadastral plans (detailed maps of land boundaries), which were believed to have been lost to time.

Searching for the patterns in our street names, she combed through thousands of long-forgotten documents: files, maps, photographs, newspaper clippings, official decrees, and the minutes of meetings held over a century ago – much of which were uncatalogued.

“I’d set myself a hard task,” she smiles. “Limassol has had a comprehensive street name registry since 1911. But no such thing existed for Nicosia – nowhere was there a comprehensive record of street naming and renaming down the decades.”

During the British era, new street names had to be approved by the Commissioner, but the duty of naming or renaming our streets has always fallen to the municipal councils of each town. And this renaming, says Stella, was often a message.

“In 1960, for example, the municipal councils were given a list of EOKA martyrs from which to choose street names. It was a highly political act, and the message was clear: we will commemorate those who sacrificed themselves for our ideology, and you will be forced to use their names every day. Every time you provide an address, write a letter, or give directions, you will be honouring our fallen.”

Many of the streets called after British royalty were renamed in this way. Edward VII became Markou Drakou. Churchill Avenue became Kyriacos Matsis. Queen Elizabeth became Michail Karaoli. And Queen Mary became Andreas Demetriou.

“Whenever identity changes or develops, so too do our street names,” Stella explains. “There’s always a narrative, and it’s always fascinating…

“In 1975, a referendum was held, and Metaxas Square was renamed Eleftheria. This de-commemoration was an act of resistance,” she reveals, “a new vision. The people had spoken. And what they were saying was ‘we don’t want dictators, we want freedom’.

“Then there’s Ledra Street,” she adds. “If there’s one street that carries the whole history of Cyprus, it’s Ledra.

“Originally Ledra was three streets. As the city developed, these were combined over time into one, which was known colloquially as Makridromas – the long street. During the struggles, it was nicknamed Murder Mile by the British. Now, of course, we all know it as Ledra, after the region’s ancient city-kingdom. And yet it’s a dead end – without a passport, the main street in the island’s capital just ends. A symbol of our ongoing division.”

What began as Stella’s PhD research ultimately became a book: Street Naming and the Politics of Greek-Cypriot Identity: The Case of Nicosia (Lefkosia) 1878-1975. It highlights how our island’s identity has long shaped the street names we now take for granted.

“Even today, streets are still being named for the same narrative, a product of our struggle in the political or economic or cultural arenas,” she concludes. “Until we see significant change in a stagnated situation, our streets will continue to be named for the most important part of our identity: Cyprus’ struggle for freedom.

“Every time we step outside our door, our streets speak to us: Remember our struggle, they say. Honour our heritage. We will not forget.”

For more information on Stella’s work visit https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-54415-6

Click here to change your cookie preferences