This is the second part of an account of the experiences of the 19-year-old National Guardsman, Kratinos Pyliotis who served as a sergeant at an artillery unit in Athalassa, in 1974. Today’s instalment is based on his recollection in the lead up to the second Turkish offensive of August 14.

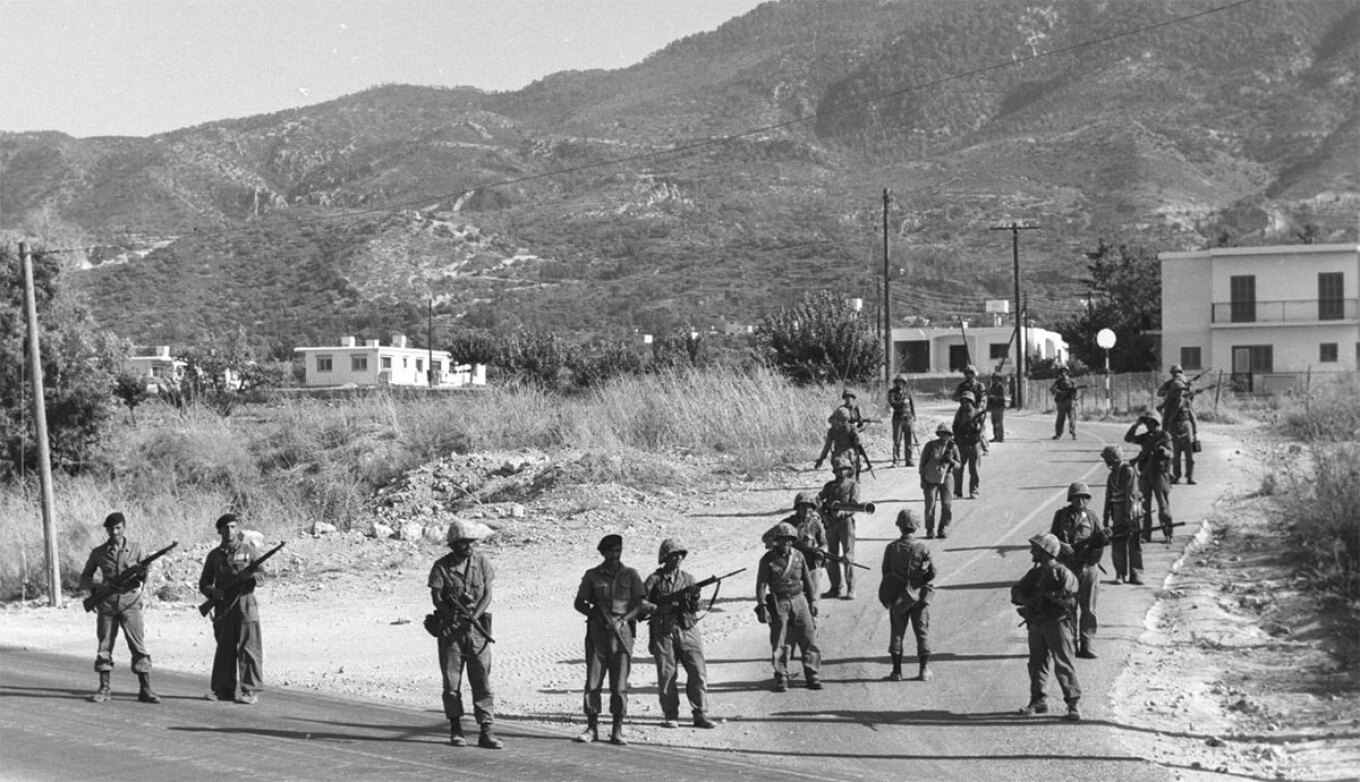

ON AUGUST 9 or maybe 11, with negotiations between Greece and Turkey set to restart (I was praying they would be successful), my unit was deployed just past the Mia Milia industrial zone, on the road to Famagusta and not far from the airstrip at Tymbou. Whether it was to protect the airstrip from Turkish aircraft bombing or to shoot down Turkish planes I do not know, but I was rather miffed that I was yet again close to an airstrip.

My unit was the furthest away from the base (a typical Cypriot house of the 1960s big enough for my superior Captain Roussos and his sidekicks) while the other anti-aircraft unit was on the side closer to Nicosia. I rang my parents and told them where we were stationed and, sure enough, they paid me a visit.

I had heard rumours that my very good friend since childhood in Famagusta had been blown to smithereens during an air attack on his camp in July. I dismissed it as a rumour but mentioned it to my mother. She did not reply, but she looked at me and her eyes watered and I knew. Cried and cried but got myself together soon enough. Had no choice.

The night of August 13 was a very nervous one and sleep didn’t come easy. If the negotiations in Geneva broke down, we expected the foes of Hellenism to continue their efforts to teach us who is the boss of the region.

My anti-aircraft unit consisted of four of us – the truck driver, the guy shooting the gun, the supplier of the ammunition and me as the sarge. One of the four was also the wireless operator and by now we also had a reservist in his late 30s with us.

Well after midnight, while we were all awake, much to our disgust, vehicle lights appeared on the Famagusta road to Nicosia. We could not hear the engine but could see it was approaching our position. We all went into the individual trenches we dug, (which was a good size for a quick burial if the unthinkable happened, albeit we would not be in the conventional full-length position) and as the man in charge I told everyone to have their rifles ready,

At last we hear the engine and a military jeep appears and stops about 100 metres away with its engine still running. ‘Alt I si’ [ the guard’s call to person approaching] boomed my trembling voice, once, twice and again. Nothing, no response. I gave it one last go, shouting as loud as I could, but again no response.

The car starts moving at speed. I felt so excited. Just like in the movies I was about to give the order to fire and try and kill someone who was likely wanting to kill me first. I heroically uttered ‘fire’, and we did just that with all our practised skill and expertise at shooting. The jeep, or whatever it was, drove past us at full speed and not one shot was fired back at us.

We were safe, but this danger was driving towards the base of the battalion. The wireless operator ran to send a message back to base that an enemy vehicle was approaching, but to nobody’s surprise, the wireless battery was flat. I took the responsibility of running the 500 metres to base to see that everything was OK and forewarn them that a danger was lurking in the dark.

A few minutes later I stood in front of Captain Roussos ready to give my warning and account of our heroic actions when he just said: ‘I should shoot you on the spot. You just rattled a UN jeep with bullets and you’re lucky no-one was killed.’

Hang on, I thought to myself. Not only are Turks prepared to kill me without caring if I am a good kid, but my Major [Gotsis] on July 15 threatened to shoot me and now a month later my captain also wants to do the same to me. Despite my account of what happened, he was frothing like a freshly brewed cappuccino. I slowly made my way back to the truck thinking that this shit has got to stop happening to me.

But I do admit this was one miss I am proud of. How none of our bullets hit them is a miracle because we fired a lot.

The first instalment of Pyliotis’ memoirs appeared on Sunday, July 21. The last instalment will appear on August 14

Click here to change your cookie preferences