Documenting the island’s waters for decades, one photographer swings between enthusiast and environmentalist in his love for the sea

Sakis Lazarides doesn’t live in Nicosia (or even Cyprus). That’s just where we happen to meet, at the Arabica Coffee House in a nondescript corner of the capital – which, in turn, happens to be across the road from the central office of the Cyprus Greens. I point out this happy coincidence – but he’s not entirely sure it applies, keen to make clear that he’s not a politician or expert environmentalist.

“I am not a marine biologist,” he tells me, speaking – as he does – in a direct, deliberate manner. “I am just a photographer, an underwater photographer. I have been documenting the Cyprus waters for decades, and I have lots of photographic evidence to back up what I am saying.” But “I’m not an expert,” he repeats. “I’m just an observer.”

One might call him an intermediary, a messenger from the depths, bringing to light all the things we’re unable to discern from above the water. His photos are popular in themselves (he sells up to 100 a month), featured in the likes of National Geographic – but they’ve also been used, for instance, by the WWF (World Wildlife Fund) in Sakis’ home base of Norway in the course of suing the Norwegian government for deep-sea mining, simply as a document of the biodiversity being threatened beneath the surface of the fjords.

62-year-old Sakis is, in that sense, an environmentalist – and indeed we talk about eco-matters, like the recent takeover of our local waters by invasive species. Mostly, however, he’s an enthusiast, reeling off the Latin name of this or that fish, or regaling me with snippets of sub-marine life.

“The octopus is a delicacy for lots of species,” he observes. “For instance, the moray eel loves to eat octopus. The dusky Mediterranean grouper loves to eat octopus.” The dusky grouper is also quite photogenic – and also the subject of Sakis’ latest book, published a couple of months ago, “a photographic guide of the magnificent Epinephelus marginatus” according to the blurb at Amazon.com.

Or how about this snippet: “You have the cardinal fish,” he says – we have three kinds in Cyprus, two of them recent arrivals from the Red Sea – “they are the so-called ‘mouth brooders’. It means that the male keeps the eggs in its mouth until they are mature. And when the fry is ready to come out” – ‘fry’ is the term for baby fish, hence ‘small fry’ – “it opens the mouth like this, and expels them into the water”. Sakis opens his mouth and blows out violently, presumably trying to disperse the baby fry as much as possible.

He’s not entirely what I expected. His photos are glossy, often spectacular to look at (a selection is available at sakislazarides.com) – yet he himself is bluff and unpretentious, with a stocky build and big, toothy grin, his Cypriot accent still pretty thick despite his decades abroad.

He’s lived in Scandinavia since 1984, having moved to Sweden with his ex-wife then found work in Norway – where salaries are higher – after they separated 25 years later. (They have three children, all now in their 30s, and four grandchildren.) At the time, when he met the ex, Sakis was working as a lifeguard in Limassol, having moved there from Famagusta after the invasion.

Was he quite an adventurous lad, I ask – feeling like I already know the answer – or more the studious type?

“I was more of the adventurous kind of boy,” he confirms with a big laugh. “I wasn’t stuck to my reading desk with books – I was out playing!”

Easy to imagine him as a young boy, snorkelling with friends, then – inspired, he says, by Jacques Cousteau – taking diving lessons at the Limassol Nautical Club, which segued into photography. (He credits one Albert Voskeritchian, who owned a camera and “inspired me and many others to dive, and love the sea”.) In Sweden he initially worked as a welder and commercial diver – then decided to become a teacher, mostly to take advantage of the long holidays. He still teaches, spending about three months of the year in Cyprus while pursuing underwater photography as a hobby (or passion) both here and in Norway.

His energy retains a boyish streak, driven by the thrill of exploring the depths. Just recently, he reports proudly, he took an unusual photo at Cavo Greco: a male seahorse in the process of giving birth (the dad has the babies in that species), a rare instance of such a photo snapped in the wild instead of an aquarium, with a profusion of other species – a baby lionfish, a long-spined sea urchin, orange and purple sea sponges – also in the frame.

Was there an element of escape too, at least initially? Diving, after all, is a solo activity and he’d always been an outsider, flung from Famagusta to Limassol, then Cyprus to Sweden – but he shakes his head.

“No, it’s not a question of escaping the world. It’s a question of entering a more exciting world.” Diving is a thrill in itself, letting your body roll, floating in a kind of aquatic limbo. “You don’t have any weight,” explains Sakis. “You feel like an astronaut in space.”

That said, his precautions are those of a middle-aged man rather than a boy. “I choose carefully where I’d like to go diving. I choose shallow waters, protected bays where I can always orientate myself, where it’s always close to the shore.”

He dives alone, usually at night; most of his photos are taken at a depth of between one and five metres. “I try to stay away from the depths. Because the deeper you dive, the less time you have and the greater the risks you take… I feel safe at all times. I have enough air, plenty of air. I don’t risk anything.”

How big is the camera?

“The camera is actually very, very big,” he replies with a laugh. “I mean, if I hold it up, it’s as big as my chest. It’s a small camera body, it’s the Canon R5… But then you have the aluminium housing, which is a big thing. And then you have the arms, you have the floats, you have the flashes, you have the focus light, you have the extra lenses you put in front…”

The whole kit weighs about 15kg, though most of that weight disappears in the water. It’s also, of course, an expensive hobby. “I have invested, in the last 20 years, almost €100,000 in camera equipment,” he admits. This is where the Norwegian salary comes in handy – especially because, until quite recently, he lived across the border in less expensive Sweden, commuting daily.

The flashes in the camera kit are especially important. Sakis’ photos are so pristine, the colours so vibrant, I’d assumed they were Photoshopped – and it’s true he does some “post-editing,” like all photographers, but no, he assures me, “the colours are the actual colours”. It’s just that you won’t see those colours underwater. “Water absorbs light”, and the red part of the spectrum goes first; “Everything appears to be blueish, greenish, greyish. These are the colours you see at great depths.”

His flashes bring out the true colours. His lights, meanwhile – the focus lights and search lights – “attract life”, especially at night when his subjects are out in force. Fish see the lights and stay still, mesmerised.

Even the silver-cheeked toad fish that’s been in the news lately – mainly because it’s extremely poisonous, and the fisheries department has put a price on its head – “they swim towards me, and sit on the sea bed only a few centimetres from my camera… But, you know, they do not bite me, they do not attack me. They just watch me, because they’re attracted by my lights”.

Ah yes, the silver-cheeked toad fish… Sakis, once again, is not a marine biologist – but you don’t need a degree to know what’s going on down below. “During a dive,” he says, “I can count up to 10 to 20 invasive species, and almost none of the endemic Mediterranean species. So they have taken over. That’s a fact.”

There are other issues. Climate change, and the rising temperatures that threaten to turn the Med from sub-tropical to tropical. Pollution, often caused by farming fertilisers washed into the sea. So-called ‘ghost nets’, abandoned by fishermen and still trapping hundreds of tons of fish every year.

But the biggest reason why Norway’s underwater is “much richer than here” is indeed the invasion by new, often poisonous species, flooding in through the Suez Canal and – a less obvious path – through ballast water that ships take onboard in the Indian Ocean and empty in the Mediterranean, releasing alien organisms into the sea.

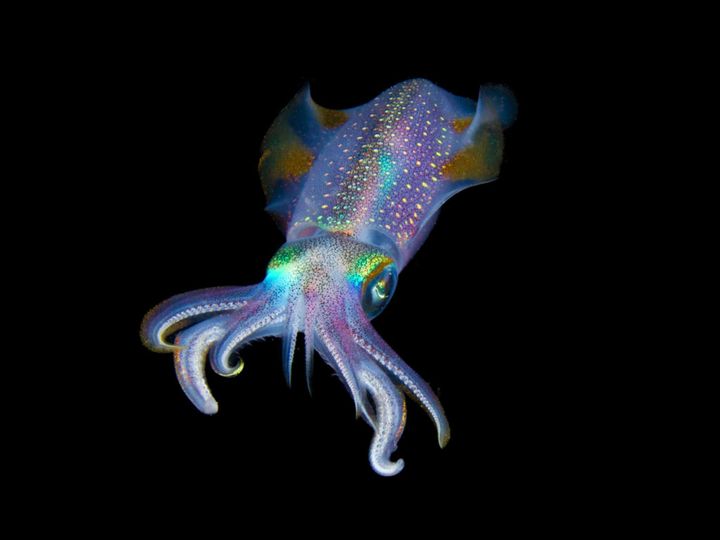

Sakis Lazarides has witnessed all this, over many years of diving down beneath the waves to take his photos of groupers and seahorses, and turtles and squids and octopuses and puffer fish – but all he can do is document it. He’s not an expert, or a politician, or an eco-warrior: he’s an observer, a messenger from the depths.

What’s he like as a person? Passionate, for sure – but also “quite humble,” he assures me, trying to do “the good thing, always”. I was wrong to suspect that diving might be his way of escaping the world: Sakis comes across as a jovial person, a people person. He still sees his kids every week, even post-divorce, and has many friends. “I try never to make enemies, and I try to mind my own business,” he declares. “Try to be helpful, and mind your own business. That’s my philosophy.”

The philosophy works with fish as well as people. He’s never been attacked, he says with a kind of ‘touch wood’ expression, and it’s mostly because he minds his own business. “You must never poke at fishes, or try to harass them… Keep your distance, take your photos and go home. Leave them alone.” Meanwhile, back on land, he appears to be a popular teacher, spending half his working week at a ‘folk high school’ (folkehøgskole) – a uniquely Scandinavian institution, a kind of boarding school offering adult education, without grades or exams, for students in their early 20s – where he teaches a course on ‘The Mediterranean’, also giving cookery lessons and going on class trips to Spain, Greece and Italy for five weeks each year. You need to have a certain personality – a warm, enthusiastic personality – to pull that off.

But the sea? Doesn’t it dampen (no pun intended) his enthusiasm to see our waters so denuded, our endemic species on the brink of extinction?

Sakis shrugs, thinking back over his life: fleeing an invasion at 12, going abroad to live at 22. He comes back to Limassol now and feels like a stranger, with all the tall buildings. He’s visited his old childhood home in Famagusta and felt like a stranger there too – though the ‘new’ Turkish Cypriot tenants spoke Greek, and had left things just as they were. And now those Turkish Cypriots themselves are no more, having sold to settlers and moved somewhere else.

“Everything changes,” he concludes. “I mean, we age, and everything changes around us. We lose friends, we lose contact. This is how life is… Even the underwater world changes as well, of course it does.”

Everything changes, in Nature too – or especially in Nature. Evolution will take its course. Species will learn to co-exist, and some will die out. Already we have some exciting news: the dusky Mediterranean grouper may be learning to eat the lionfish, despite the latter’s spiny appearance. “I have seen with my own eyes,” reports Sakis, “a grouper attacking and eating an injured lionfish.” The underwater world will find its balance. And Sakis himself?

“My only interest is to make beautiful photos, and show them to people,” he replies simply. “That’s what I do.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences