By Andreas Charalambous and Omiros Pissarides

Until recent years, international financial organisations supported the view that narrowly defined fiscal discipline was an absolute prerequisite for long-term sustainable growth.

The foundations of the EU rested on this theorem, manifested, among others, in the establishment of strict quantitative fiscal rules, for example containing the fiscal deficit and public debt below the 3 and 60 per cent thresholds of GDP. This rather restrictive policy approach was implemented in recent crisis episodes, including in Greece and Cyprus.

The financial crisis of 2008 and, more evidently, the current pandemic led to radical rethinking. Governments were forced into unprecedented public expenditure increases, which, in turn, led to historically high levels of public debt, for example Greece, 200 per cent, Italy, 160 per cent, and Cyprus, 120 per cent of GDP. In the past, such circumstances would have led to steep increases of sovereign debt interest rates, reflecting the enhanced fiscal risk, and inflation pressures while international organisations would have warned about the severe adverse repercussions.

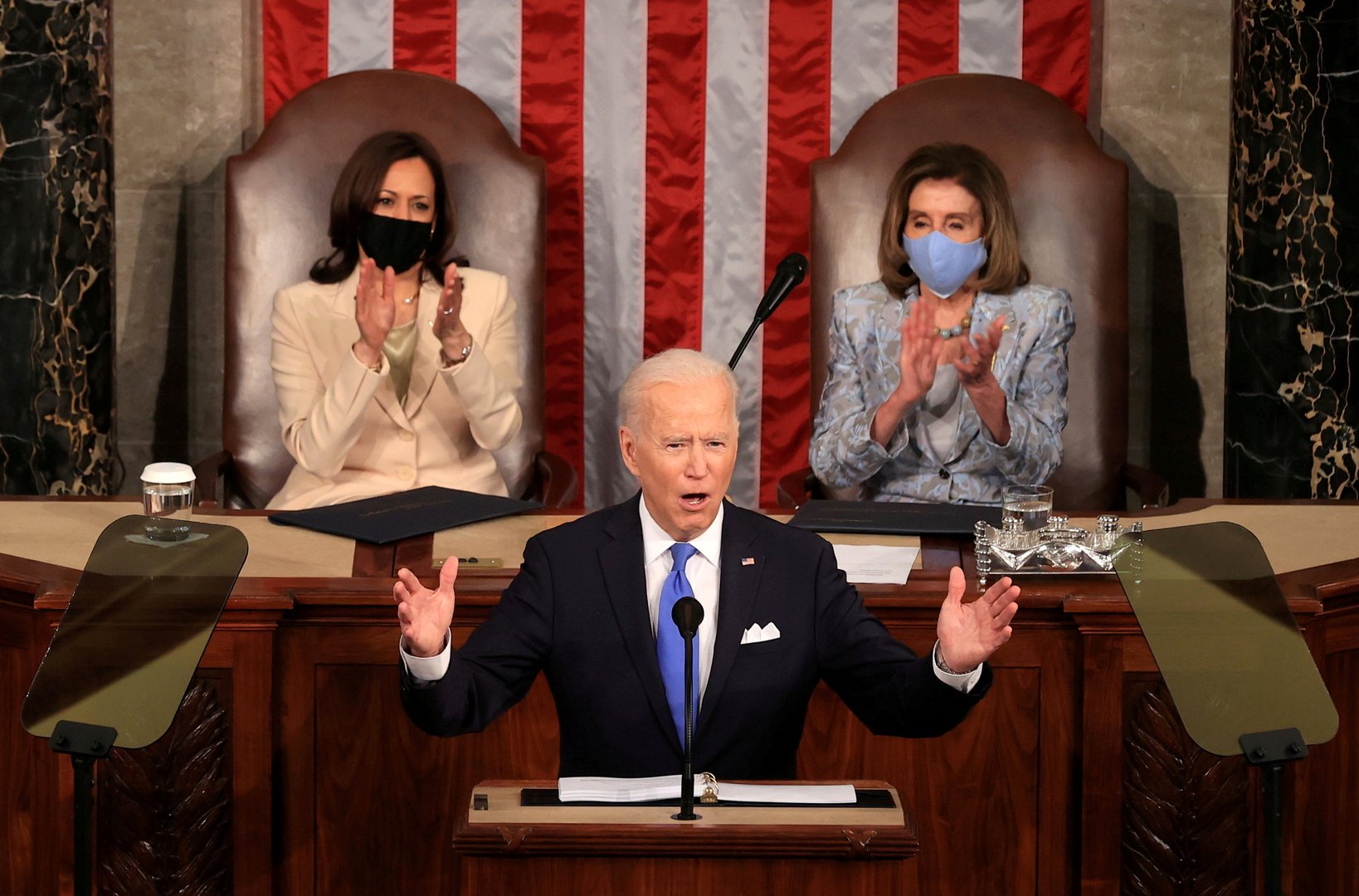

None of the above is happening. The sovereign interest rates remain at historically low levels, even for vulnerable economies, the European Commission postponed the implementation of the strict rules-based fiscal framework, the Biden administration announced the most ambitious fiscal support programme in the US’s recent history while central banks across the developed nations continue purchasing government bonds on a massive scale, thus facilitating the implementation of expansionary fiscal policies.

Opposing views still exist and were publicly expressed by, among others, the former finance ministers of the US and Germany, Mr Summers and Mr Schäuble, both emphasising that when the adverse repercussions of today’s policies (excessive inflation, low productive investments, overheating of certain sectors and so on) become visible, it will be too late to take effective corrective action.

Taking the above into consideration, where do the boundaries of fiscal support policies lie? This is a genuine question whose answer is not straightforward. Certain evidence can, however, provide guidance to government fiscal policy approach.

The high overall level of savings in a global context, due to structural factors of permanent nature (technology, ageing population, etc), enables extended government borrowing compared to the past, without adverse repercussions on the market lending rates and private investments or excessive inflation pressures. This proposition is particularly valid when borrowed funds are diverted to sustainable investments and social cohesion enhancing measures, thus strengthening growth and creating the financial means for future debt repayment in a viable manner.

According to this new policy approach, the focus of attention is no longer the nominal debt level, but (a) the targeted utilisation of borrowed funds for long-term productive purposes while avoiding wasteful expenditure based on politically-motivated pressures, and (b) sustaining a downward trend of public debt, by safeguarding that the nominal economic growth rate remains higher than interest payments. Moreover, the boundaries of fiscal policy are not uniform, rather they depend on country-specific structural characteristics.

Experience reveals that changes in market lending rates can take place abruptly. Therefore, governments should take advantage of the current benign market conditions to create a “safety pillar” thus enhancing their flexibility and ability to adapt to changing conditions. As the IMF stated in a recent report, the boundaries of government borrowing have been extended due to changing market conditions, but they have not become unlimited.

Andreas Charalambous is an economist and a former director at the Ministry of Finance. Omiros Pissarides is the managing director of PricewaterhouseCoopers Investment Services

Click here to change your cookie preferences