In a man who has cleaned up a cemetary in Bellapais and is the father of casinos in the north, AGNIESZKA RAKOCZY finds a man frustrated by the unchanging view in Varosha who is now behind the creation of a huge statue to ‘unite Cypriots’

Several years ago, a well-known Turkish Cypriot businessman took a stroll not far from where he lived and wandered upwards until he found himself atop a hill overlooking the Mediterranean. Tranquil and beautiful though the scene was, it was not the sea view that mesmerised him.

Opposite a nearly-collapsed wall, he observed a small chapel, behind which lay shattered crosses strewn among unkempt mounds that had been repossessed by weeds. Sheep and goats grazed gently among the burial sites isolated in the aftermath of division and displacement.

Erbil Arkin was standing in the middle of the old Greek Cypriot cemetery of Bellapais.

“I felt ashamed,” he recalls. Deeply ashamed and upset while looking at this scene. This day I decided I had to do something about it.”

Arkin contacted the Kyrenia Turkish Cypriot municipality and complained about the state of the graveyard. What he discovered was that after 1974 the local authorities had in fact decided to retain the site as a cemetery and to expand it by establishing a Muslim graveyard next to it.

“Unfortunately, it didn’t happen. And then some person put his goats and sheeps among the graves,” he says.

The municipality ordered the animals out and Arkin, one of the north’s most successful business entrepreneurs, offered to restore the Orthodox graveyard while also undertaking to prepare the surrounding area for a new cemetery.

A man of vast energy and vision, Arkin set about realising his project in methodical fashion.

“I knew that people still visited this cemetery. There were candles and little icons and flowers left here. So to start, in 2017, through the Red Cross, I contacted the relevant organisations and persons in the south and invited them to a meeting. I wanted to discuss with them what should be done,” he explains.

While the meeting was held in a cordial athmosphere, unfortunately, it didn’t yield the hoped for results.

“Perhaps the timing was not right,” 71-year-old Arkin surmises. Undaunted, he set about proceeding on his own. The graveyard has since been cleaned, the little chapel restored, the walls rebuilt. All the remaining broken grave stones and crosses have been gathered and accounted for so that nothing more is at risk of being misplaced or lost.

Arkin has also commissioned and overseen work on the surrounding area to prepare the ground for more burials.

In the Bellapais church yeard

“Of course the work is not finished yet,” he says. “But soon everything will be ready. As a matter of fact, one person from Bellapais was buried in the new Muslim part of the cemetery just a few months ago. She was a local lady who didn’t want to go somewhere else. And of course, I understood her wishes. This place is so beautiful. You can see both the sea and the Abbey from here.”

Nonetheless, he feels that his project cannot be completed until more is done to restore the original site, the inspiration for all that has since happened.

“At this stage, I feel that I have done everything that I could on my own. Now I really need help from the former Greek Cypriot inhabitants of Bellapais as well as from the Church,” he says.

“Frankly, this is actually the main reason why I agreed to this interview,” he tells me. “I want to appeal to them to come forward and talk to me. I don’t feel it would be right for me, Erbil Arkin, to put the cross and the icons in their chapel or move tomb stones around without them telling me where they should be. I feel the Chapel should be sanctified by the appropriate people. So I would like to say to them, please come and tell me what to do. I will finance it. The municipality will support it. But I need more information.”

Arkin believes that what he is doing can set an example for similar projects and show both communities that instead of desecrating one another’s cemeteries and places of worship through neglect or worse they can respect and take care of them.

“Several months ago there was a story in the media about the vandalism that took place in the Episkopi mosque. I read about it and got very upset. So by talking about what I am doing in Bellapais I also want to embarrass those who do things like this. Because this is the wrong way for ouor future.”

Born in Ayia Anna, a small mixed village close to Larnaca, Arkin left for the United Kingdom when he was two years old.

“My parents were poor,” he says. “My father left first and then when he saved enough money to pay the passage for his wife and three kids, we followed.”

With great admiration and affection, he recalls how his mother, a woman “who could neither read nor write”, had the courage to take her three children (aged two, four and seven), pack them on a boat to Genoa and then make their way to Calais by train.

His parents’ tough decision to uproot the entire family to look for a better life abroad is reflected in many of Arkin’s own choices and struggles. He cites their example as the inspiration for his own ‘reach for the stars’ philosophy.

“Life is like a conveyor belt in a Japanese sushi restaurant,” he says. “Each of these sushi plates represents a different chance and if you really want it you have to grab your plate when it is in front of you because otherwise it will go away. One has to take one’s chances when they come. You might be a street sweeper and have a dream of selling simit (Turkish style pretzel). What a beautiful dream it is! So if you have a chance, do it.”

“My parents had three dreams in their life: to get a roof over their head, to feed their family and to educate their children. And they grabbed their chance and went to the UK and succeeded beautifully.”

Arkin himself admits to having dreamt of reaching for the stars from a very early age, going back to when he was a small boy in East London.

“My mother worked in a sweat shop and my father was a labourer. We had nothing. But I could draw and my teachers recognised it and so going to art college became one of my first dreams.”

He made it a reality through a combination of qualifying for grants and by working in his free time – “first stacking shelves in my uncle’s shop, then washing dishes and working as a waiter.”

He eventually went to university and got a degree in Industrial design.

His next chance was to come just after 1974. He was having a drink in his local pub in Islington with a Turkish Cypriot friend, who happened to have experience in the betting industry.

“I was working as a designer. And this friend convinced me to go back to north Cyprus. He said, now we Turkish Cypriots can do something there. It is not like before. And I said ok, lets go and we went.”

Arkin was 25 years old and had no business experience of any kind yet what happened within the following couple of years was to determine his future.

“I started something here and it has switched the north around,” he claims. „You can see it either as a sin or something positive. I am the father of casinos in north Cyprus. You can love me or you can hate me. But it is a fact. You can even say I might be the reason why there is a casino in the south right now.”

Forty years on and casinos are not the only industry the now diversified Arkin Group consists of. “I have about 2,400 employees in north Cyprus, Turkey, Great Britain, Iraq, Lebanon, even Africa,” Arkin says.

“I have two casinos here but also betting shops, hotels, a golf course in the UK, a boat yard and tourism company in Turkey, restaurants, a furniture manufacturing company, even a housing development business. I am very proud to say that I started from the island and became international, and this is a very rare case.”

But the continuing situation on the island gets under his skin.

“Yes, what is happening here has been frustrating me for years. It started in the early 80s… As you know I have a hotel in Famagusta and from there I can see Varosha every day…. When I first came there, I was 27. Now I am 71. If somebody had told me then that the view would be the same 40 years later, I would have called him crazy and yet, it is still the same.”

He has many Greek Cypriot friends, readily admits that both sides are at fault and concedes he feels very pesimistic about any chances for settlement.

Arkin’s interests are varied and wide-ranging. There’s wine making, for example. He sells his own wine at his hotels and restaurants, although modestly admitting “it is not that great”. Other pursuits include salmon fishing and English style bird shooting (“I do it only in the UK and the birds are specially bred for this”). Then there’s tennis, horse riding, and sailing. The last of these led him into boat designing and building (“the boatyard that built my boat was in trouble so I bought it”).

However, art remains his greatest love and if he regrets missing anything in his life of many pursuits it would undoubtedly be not having the time to devote himself more fully to making art himself. “I started painting again in the 90s but realised I couldn’t because it was all consuming and business suffered so instead I started collecting.”

His collection of Rodin sculptures is his pride and will be his legacy to the island, if his dream of building a large art museum in the centre of Kyrenia – his ‘Guggenheim’ as he fondly calls it – becomes a reality. For the time being, he has created an art space on the lower floor of his headquarters where he exhibits most of his Rodin pieces, notably one of the master sculptor’s bronze casts of the iconic Kiss.

“Everybody is welcome by appointment to come and see them,” he tells me. “All the descriptions are in Turkish, Greek and English, so everybody can enjoy it.”.

I asked how he explains this passion for the great French sculptor.

Arkin traces it back to a visit to London’s Tate Gallery when he was an art student. Then, he adds, it reignited in the early 2000s when, by chance, he visited an art gallery in St James’ and was invited to a Sotheby’s auction.

“I walked around and there was this marvelous sculpture by Rodin, that I knew very well. Then the bidding started and my friend asked me if I wanted to bid and I said yes. Suddenly I owned a Rodin,” he remembers.

He talks about other art projects like the Arkin University of Creative Arts and Design, that he set up in 2017 out of frustration at what he describes as the “lack of artistic culture in the north”. And most recent, of course, there is now the project for the huge statue of the Noble Peasant, perhaps his most controversial idea, that has generated a wave of very mixed emotions among Greek and Turkish Cypriots.

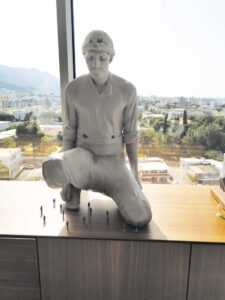

a model of the proposed statue

Arkin organised an international competition inviting sculptors to submit designs for his Noble Peasant concept that would be suitable for placing on the face of the Pentadaktylos Mountains. The winner was the Dutch sculptor Lotta Blokker.

Unabashed, Arkin explains his reasoning.

“I wanted it to be Cypriot and to have nothing to do with politics, race or religion, hence the subject. It will be made of bronze, and will be two metres taller than Rio de Janeiro’s Christ the Redeemer,” he says.

“It will put Cyprus on the map. Not only this side but the south as well. It will show people that even a small island can do it. It will make money. It will mean many things. It will be unifying. Now that word of this project has come into the open, people are complaining about stupid things. They say it will face Turkey for example. But the truth is this statue will define Cyprus for the next 100-150 years, and it will stay here long after the current issues disappear. Like St Hilarion Castle.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences