By Shadia Nasralla and Tom Hals

A Dutch court’s decision to force Royal Dutch Shell to make deeper, faster cuts to its climate warming emissions on the basis of human rights could set a precedent, especially in European countries, according to lawyers and activists.

The court last Wednesday ordered the Anglo-Dutch company to slash its global greenhouse gas emissions, which stood at around 1.6 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent in 2019, by 45 per cent by 2030. Shell said it would appeal the decision forcing it to cut by an amount roughly equivalent to four times Britain’s annual emissions.

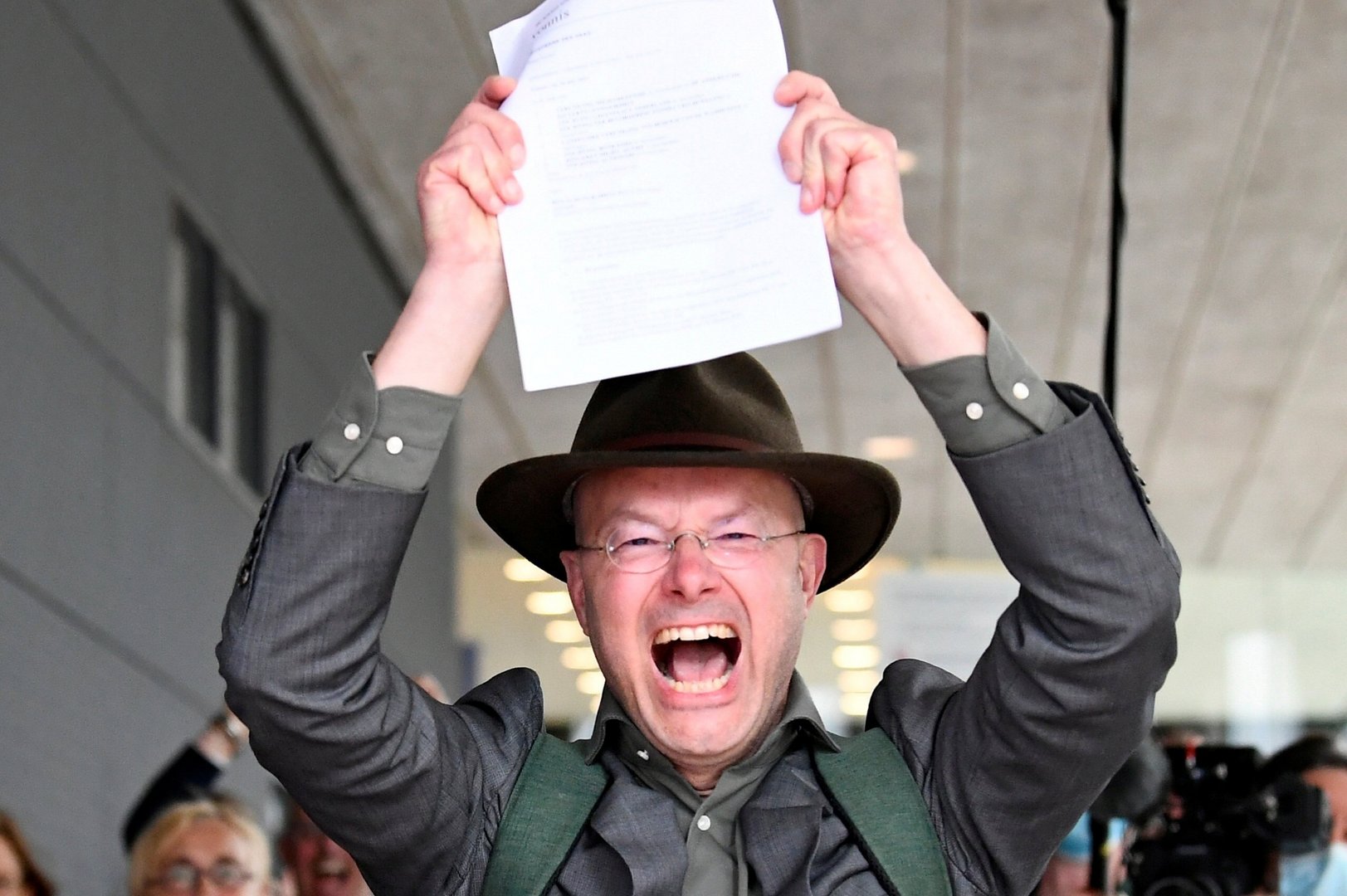

“We expect a ripple effect into other jurisdictions. Now that we have this first established liability, it definitely creates a momentum we can build on,” said Roger Cox, lawyer for activist group Friends of the Earth, which brought the case along with Greenpeace, other activists and Dutch citizens.

They brought the lawsuit in the Netherlands, where Shell’s headquarters are based.

The court held that Shell violated its duty of care under Dutch law because its policies and emissions contributed to dangerous climate change.

Shell had argued that its global emissions were not subject to Dutch law, that the plaintiffs’ claims were a matter for lawmakers and that the company was acting lawfully and its emissions were permitted. The company also said the plaintiffs could not establish that reducing Shell’s emissions would have an impact on climate change.

Michael Burger, a litigation specialist who represents local US governments in climate cases including against Shell, said while the decision was based on Dutch law, the concept of a duty to care exists in legal systems in Europe and around the globe.

“I think it’s quite likely that we’ll see other lawsuits filed in other jurisdictions, seeking to accomplish the same thing,” he said, noting a similar case is pending against Total in France.

Myfanwy Wood, dispute resolution partner at law firm Ashurst, said duplicating the approach will depend on the standard of care that applies to corporations in other jurisdictions.

Dutch climate rulings have inspired global climate litigation before.

In 2019, the country’s High Court ruled that the government had to commit to stronger climate targets in a case brought by the Urgenda Foundation. That decision, which paved the way for the Shell case, established that the government had a duty of care to significantly reduce emissions.

The case “sparked a wave of similar lawsuits around the world against governments, and we can expect that with the decision yesterday,” said Louise Fournier, a climate lawyer for Greenpeace.

There are about 425 pending climate lawsuits in various countries and about 1,375 lawsuits in US courts, according to the Sabin Centre for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School.

The US cases target the industry, while most cases in other jurisdictions take aim at governments.

Experts said the Dutch ruling will have no legal impact on the US cases, which are generally based on different laws and accuse the industry of misleading the public about climate change and seek financial damages.

However, the Dutch ruling could still influence the US cases, said Karen Sokol, a professor at Loyola University New Orleans College of Law. She said the Dutch decision reassures US judges that climate change involves more than policymaking.

“The industry has done everything it can to scare courts into ‘you have no role,’” said Sokol. “It is going to get demystified and courts will get comfortable with it.”

European legislators are working on a raft of new rules on what type of investments should be labelled sustainable and how to reduce planet-warming leaks from natural gas infrastructure.

“This ruling (…) increases the pressure on large polluters and helps us in Europe to tighten climate policy for them as well,” said the Greens’ European legislator Bas Eickhout, Vice Chair of the European Parliament’s Environment Committee.

“They can no longer escape the climate crisis: International climate targets must also apply to them.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences