THEO PANAYIDES meets TV, West End and Hollywood actor Kevork Malikyan, a ‘little Armenian boy’ from Turkey

Steven Spielberg once described Kevork Malikyan’s face as a combination of Al Pacino, Robert De Niro and Dustin Hoffman – though in fact I only catch the Hoffman part, when Kevork smiles, a toothy, rather rabbity grin peeking out from behind his salt-and-pepper beard. Then again, times (and faces) change; he was 45 when he worked with Spielberg on Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, he’s now 78. We meet in a flat in a quiet part of Larnaca, on a strange summer’s day. Thunder rumbles in the distance as he welcomes me in, chatting volubly, thunder turns to rain and the rain gives way to sunshine – yet I still haven’t turned on my tape recorder to begin the interview. He’s still chatting.

He too, you might say, is quite an unusual man – a “little Armenian boy” from Diyarbakir in southeastern Turkey turned prolific actor in TV shows, West End theatres and (occasionally) Hollywood. He seems to have done it without even trying (the truth, I assume, is more complicated) – and, having been borne along on this wave of good fortune, seems to have decided to act the part, with an outsider’s craving to become ‘more English than the English’. He’s a gracious host, a raconteur, going off on tangents, effusive with old-world charm and the actor’s peculiar mix of posh grandiloquence and chummy humility. Here, for instance – to give a flavour of the man – is Kevork on the third series of Mind Your Language, which was filmed independently after LWT dropped the show for being controversial:

“They wanted me to be in it. I mean, bless them – Stuart Allen, God bless him, Vince Powell, God bless him, the writer – they took me to lunch. But I remember saying to my agent: ‘Maureen, darling, I don’t want to do it’. I’d had enough of playing an idiot foreign stand-up-comedy man. We cannot go on playing foreigners. Fine, yes, I am what I am, and I will do it as long as the part is decent. I’ve played Arabs, Armenians, Turks, Italians, Colombians – I’ve played almost everything, my darling – but I wanted to play an educated doctor, or a lawyer. Which I did. Once I stopped Mind Your Language, strangely enough. [So] I said: ‘Please tell them. Ask for £5,000 a week’ – in those days! ‘Darling, they won’t pay you that.’ ‘Ask, Maureen, please. If they do, we’ll do it for the money. And if they don’t…” Kevork shrugs eloquently. “And that’s exactly what happened.”

That’s the catch, of course: Brits loved the series, set in a language school where a class of foreigners are trying to learn English – but were they laughing with the characters, or at them? Even at the time, there were cries of racism – though Kevork is firm on the subject: “I personally, really and truly, never saw it that way, it was not a racist show for one moment. We said what we said to one another out of sheer ignorance, and inability to speak proper English”. Still, it’s startling to watch, for instance, Maximillian’s introduction in the very first episode. “I walk with sheeps,” he says, and the audience roars. “You’re a shepherd?” asks the teacher. “No no, sheeps,” he repeats, and toots an imaginary ship’s horn. “Tonkers,” he adds, and a woman in the live audience literally screams with laughter. Different times.

How about in real life? Did he ever encounter racism in Britain, having first arrived as an 18-year-old aspiring drama student in 1963?

“Noooo,” he replies, leaning back in his chair like a man about to savour a good cigar. “I really can’t say for one moment that I have.” He’s not naïve, adds Kevork: “Racism is inherent in every miserable society in the world. But I personally? No way. They gave me a home”. That said, he recalls a meeting – in 1967, just out of drama school – with Fraser & Dunlop, probably the top agents in the UK, who’d agreed to take him on as a client but nonetheless asked him to consider doing two things: changing his name, and moving to America. Because “in England you did Shakespeare,” he explains wryly. “You did Pinter, you did Osborne. Kevork Malikyan playing Shakespeare? But I did, 20 years later! Several times, and I’d like to think successfully. But I did it after 20 years. It took me 20 years to be sort of accepted – I think – as a competent actor.”

That last part is him being modest, of course; indeed, one striking aspect of Kevork’s story is perhaps how easily he (or his talent) was accepted, even when the odds were against him. Why was a young, foreign actor, fresh out of drama school, taken on by Fraser & Dunlop, whose clients included Sean Connery and Vanessa Redgrave? Why, come to that, was he accepted to study acting in England when he could barely speak English? (He spent a year at a language school first, like the one in Mind Your Language.) Why, going further back, was a young boy in a seminary in Istanbul chosen to be an actor in the first place? And why, going back even further, was a saddle-maker’s son in Diyarbakir plucked from his home by a prominent cleric and taken to Istanbul to study for the priesthood?

People clearly saw something in him – but what? A presence, an intensity, whatever. His origin story is unusual, to put it mildly, furnished with unlikely guardian angels and haunted by the spectre of the Armenian genocide of 1915. (He himself has made two films about the genocide, The Cut and The Promise.) Kevork’s parents were both children during the massacres; they never really spoke about it later, though his mum had been in the arms of her own mother when the latter was shot and killed, and his dad – born to a rich family in Sivas, in central Turkey – had somehow ended up in Diyarbakir hundreds of miles away, secretly raised by a Kurdish family. He worked as a saddle-maker but also spoke five languages, and even municipal officials used to come to him to write their letters for them; in a different life – and had he not lost everything in 1915 – he might’ve been a famous writer, or an intellectual. “He was a beautiful man,” sighs his son. “I would like to think that – I’m him.”

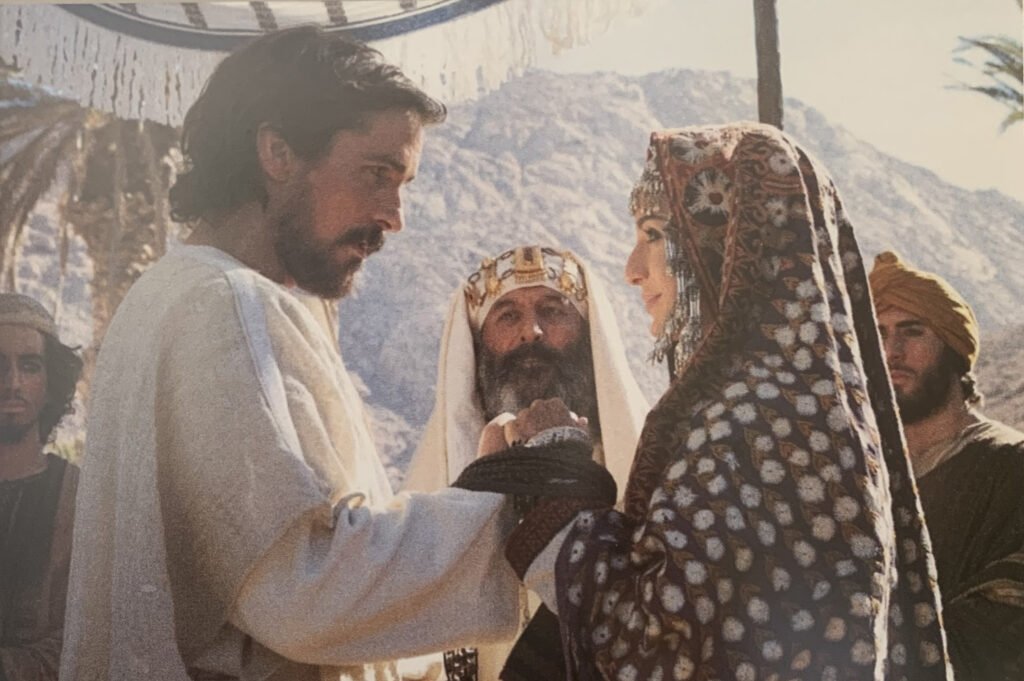

In a way, the opposite is true: far from being his father, Kevork is his antipode, the yin to his yang. It’s as though the universe, having wronged the elder Malikyan so badly, felt an obligation to balance the scales with his son, giving Kevork the breaks it took away from his dad. To be sure, the boy had something – “a busy little boy,” he calls himself, “always doing naughty things”; he was always attracting the attention of grown-ups, albeit mostly for the wrong reasons. But then, when he was 10, a priest came along – collecting children from poor families for the Armenian seminary in Istanbul – and took him away when he might’ve stayed in Diyarbakir “and died by now, probably, or become a shoemaker, or a butcher”. And then, when he was 18, happy enough at the seminary, an English teacher called the Rev. David Harding put on a production of Richard III – and was so impressed by Kevork, his lead actor, that he arranged auditions for him at three UK drama schools. (Years later, there was an emotional reunion when Harding officiated the wedding of Kevork’s daughter Sonia.) Then Rose Bruford of the Rose Bruford College once again saw something in the boy, and asked him to cancel his other auditions and take a place with her – and, a week after graduating, he was already rehearsing the Porter in Macbeth at Derby Playhouse. (Sonia, incidentally, was born halfway through that production.) It all came easily; indeed, it was almost too much.

What was he like at 25, say? “An idiot,” he replies. “A lost boy… You know, sometimes it’s like being caught in a river and you allow the tide, the flow of the river, to take you. Because you’re not wise enough, not knowledgeable enough, not mature enough to question, what is it that I’m doing? Where is it that I’m going?”.

Looking back, his life was like a river, rushing from stage to screen, production to production – and the money was good, he recalls, and “we had a wonderful lifestyle, we used to wine and dine at Le Caprice, Langan’s, all these places”. He drove fast cars, co-ran an Armenian restaurant for a few years, liked the good life in general; “I was a naughty boy on occasions,” he chuckles, and says no more. The wife and kids didn’t see him very often but well, that’s the life of an actor – and perhaps he took too many ‘ethnic’ roles but he also hit the jackpot occasionally (he was indelible as the prosecutor in Midnight Express). “Did you do everything right?” he pleads. “Do any of us do everything right, or get it right?… There are hundreds and thousands of actors out there who would love to have had the career that I’ve had. I would love to have the career that De Niro’s had, or Al Pacino. But life isn’t like that. Life isn’t fair, and the profession isn’t fair.”

Mention of Midnight Express (seen as an anti-Turkish film in some quarters) brings up another point: Kevork’s relationship with his country – and his status, in effect, as a man without a country. He was actually offered a role, pre-pandemic, in Once Upon a Time in Cyprus, the recent, lurid Turkish TV drama set in 1960s Cyprus: he could take his pick of Makarios or Grivas, he was told. He’d rather play Rauf Denktash, he replied slyly – already knowing the answer – sparking confusion and bewilderment: ‘But Denktash is a Turk!’ said the producers. Kevork is well-known in Turkey (hence the excitement of that checkpoint guard) yet he’s also an Armenian first and foremost; almost but not quite Turkish – he actually lost his Turkish nationality for many years – just as he’s almost but not quite British. An unusual man, in more ways than one.

There’s perhaps a slight solitude behind the chatter and youthful energy. I ask about friends but he doesn’t have a lot of close friends, “not really”. “I can’t play the famous game,” he tells me later; he’s no good at pretending to be friends with celebs. He seems to have a horror of being thought pushy, or parasitical. Above all, perhaps, being a foreigner – someone who fought to be accepted, who often played slightly demeaning roles – he insists on his dignity, and is sensitive to being disrespected. There were only “two people I had problems with” over the years, he says, Warren Beatty and Steven Seagal (in Ishtar and Belly of the Beast, respectively), in both cases because they were arrogant: Beatty was always late to the set, Seagal treated him like dirt and wouldn’t even do him the courtesy of standing off-screen while Kevork did his half of their dialogue scenes. It’s not right, after 55 years in the business.

And now? “‘So what do you do next, Kevork?’,” he chuckles. “‘What is it you haven’t done so far, that you want to do in the future?’ Surprise element, I don’t know!” He’d like to end up in Istanbul eventually, he muses, if and when he retires, maybe open a theatre or a cultural centre – but first he needs to get out of the flat in Larnaca, get on a plane and get back to work. “I think my passion is my work,” says Kevork Malikyan, then adds a postscript: “And my passion is talking too much.” Perish the thought.

Kevork is on Twitter, at twitter.com/MalikyanKevork

Click here to change your cookie preferences